Back To School of the Holy Beast: A History of Nunsploitation

I had just gotten to Emerson College when Kyle Glowacky, head of the screening club Films from the Margins, invited me to watch School of the Holy Beast (1974). This gently demeanored sailor told me there was a fairer than average chance the school’s catholic club would protest the screening; it had happened before. I had never heard of this movie but as the old saying goes: don’t threaten me with a good time. And so that night I got my first taste of what audiences approaching public premiere screenings of Paul Verhoeven’s Benedetta have been experiencing lately. The joyousness of having your fetishes (borrowed for the evening or careworn) picketed by concerned Catholics, of becoming part of the movie for the evening, and the sinful pleasures of that disgraceful genre known to heads as Nunsploitation.

Severin Films, one of the great releasing houses in the world, have lovingly restored four of the most stunning examples of the form in their gorgeous new boxset Nasty Habits. With luck they’ll remind people of the history behind the latest flowerings of the idea of nuns gone wild.

For such a finite grouping of initial works in the movement, the term Nunsploitation has managed to hang in the culture quite firmly since its origins (the most potent ideas do tend to dig in like soldiers on a beachhead). Any sleaze scholar will tell you that the movement properly kicked off in the wake of Ken Russell’s 1971 Aldous Huxley adaptation The Devils, scaring up a paranoid reaction from officials and the public alike. Warner Bros caved to the demands of Catholic groups and censors, removing some footage that has still never been put back in. In the 60s, 70s and 80s, where fuss went, Italian knock-offs followed.

Related: God of Power, God of Fear: Religion and Self-Righteousness in ‘Midnight Mass’

But of course Russell’s film wasn’t even the first adaptation of Huxley’s 1952 historical narrative The Devils of Loudon. The book chronicles a shameful chapter in French clerical history where witch hunters were brought to a convent to torture and coerce the nuns into a frenzy of supposed demonic possession. They did this to blame it on the sex appeal of a progressive priest who had free reign of his parish in Loudon and rejected the orthodoxy of the church. The priest in question, Urban Grandier, was burned at the stake in 1634.

Eyvind Johnson wrote his book on the subject, Dreams of Roses and Fire, three years before Huxley. By 1961 the events were dramatized by Marxist politician and occasionally award-winning filmmaker Jerzy Kawalerowicz in 1961 as Mother Joan of the Angels (it opens with an image of a priest lying prostrate on the floor while the credits cross his back like the scars of whip strikes, presaging the violence to come). Avant-garde composer Krzysztof Penderecki turned the novel into an opera in 1969, which was filmed and released a few years later.

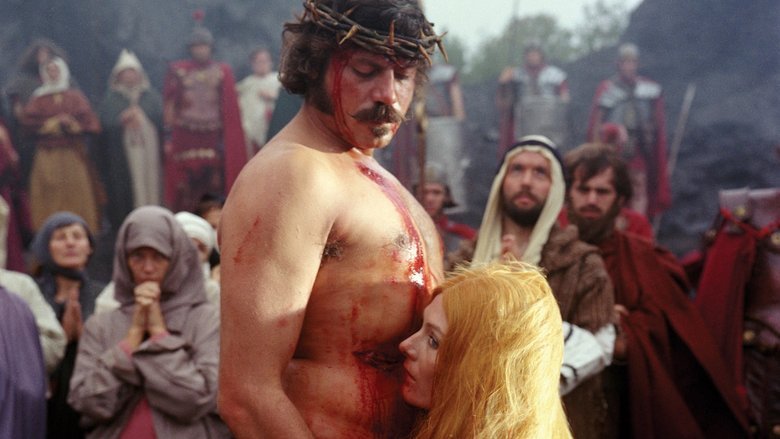

By the time Russell made The Devils, his best film and indeed one of the greatest films of all time, the world was ready for this story to be told in color, with Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave matching wits as the horniest characters ever committed to film. Hysteria was coming.

Related: Losing Religion and Finding Spirituality Through Horror

The Loudon possessions were only one inciting incident waiting to be exploited by the enterprising (or maybe salivating is the better word). The Nun of Monza, née Marianna de Leyva y Marino, was a real forced convert. She was 13 when her father gave her to the convent, which is how those used to stay in operation, men with debts would give their kids up to square their accounts (Benedetta dramatizes this with the sadistic glee typical of its director, perennial prankster Verhoeven). She had two children out of wedlock and helped murder the nun who found out about it.

Paintings of the Nun of Monza make her look like a thin, thick-browed goth (she’s cute!) and that look wasn’t quite in fashion. So no cinematic rendering of her looks quite right. I have to assume Abel Ferrara knew what she looked like because when he puts Zoe Tamerlis in her nun costume in Ms. 45; that’s about what she looked like according to conventional renderings.

The first adaptation of her story came courtesy of Luchino Visconti’s upstart nephew Eriprando in 1969, though he was far too polite. Benedetta Carlini, Verhoeven’s heroine, was a real nun and supposed mystic who had radical visions of Christ. She also engaged in homosexual congress with a novice at the convent, and was treated only slightly better than Urban Grandier. Maria Domitilla Galluzzi wrote of visions of the Holy Spirit and bystanders claim to have seen her levitating while under his influence.

Related: The Unholy Transcendence of ‘Midnight Mass’ and ‘Saint Maud’

And before both of them, there was St. Teresa of Ávila, who spoke of being taken advantage of sexually by an angel (in 1989 Nigel Wingrove turned these stories into the short film Visions of Ecstasy, still the only film ever banned for blasphemy in England). Les Lettres Portugaises, published in 1669 created quite a stir as they were supposedly written from the perspective of a woman in a convent expressing love for a man of nobility. The author has never been definitively confirmed, though many have their pet theories. And bringing up the rear is Denis Diderot’s novel La Religieuse, published several years after his death, which saw a woman sold to a convent to hide her parent’s shame and finding little else but more shame inside. Jacques Rivette adapted this first in 1966 with Anna Karenina.

With all these stories making their way to a public hungry for some proof that those chosen by God were just like us, it’s little wonder that Convent Pornography and early notions of Nunsploitation became genres unto themselves sometime in the 17th century and not just in Europe; it traveled basically everywhere. The Marquis De Sade was only the most famous artist to spin erotic yarns about the sex lives of nuns. His novels weren’t properly adapted until censorship started easing in France. Erotically minded Roger Vadim, unsurprisingly, was the first person to tackle his work though he transported the setting of the novel Justine ou les malheurs de la vertu to Nazi-occupied France.

Related: Faith and Fear Make ‘Midnight Mass’ An Affirmative Experience

Even less surprising was the next man to try his hand at adapting the book, Jesús Franco. Franco is to filming sleaze what Omar Rodriguez-Lopez is to music; he arranged ten thousand variations on the three or four themes that most interested him, each spellbinding in their own way. At a time when the world’s hunger for grindhouse was insatiable, he was truly the only man capable of feeding everyone at all times. Not only did he make several movies based loosely on The Marquis de Sade’s writing, but he also directed the exquisite Letters of a Portuguese Nun, loosely based on Les Lettres Portugaises.

So between the first cinematic representation of Nuns courtesy of the likes of Julie Andrews and Audrey Hepburn, there’s also the birth of what Lindsay Hallam terms Decamerotica in her video essay Sisters of Vice and Virtue, included in the boxset. These were films that take the borderline pagan sexual freedom of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron novels as their starting point. Obviously, Pasolini’s more or less straight adaptation from 1971 is as good a place to look for the ideal form that story would take, but it was about one of 20 from a five-year period.

Related: “The Best View of God is From Hell”: Rage, Guilt, and THE EXORCIST Prequels

There are also witch-burning films to take into consideration. After all, The Devils ends with one, and we’d seen a goodly sum of that from the mid-60s through the 70s in forms elegant (Witchhammer, 1970), tawdry (Mark of the Devil, 1971) and/or both (The Conquerer Worm, 1968). All of these ideas — the epistolary novel, the pagan ritual, the sapphic nun story, the witch burnings, the misleading adaptation — meet in 1977s Alucarda by Juan López Moctezuma, the greatest of the religious hysteria movies to follow in The Devils’ frenzied footsteps. It ends with a full reel of blood and screaming as nuns in tight wrappings come to look like used tampons while a goat-like devil presides over the resurrection of a novice. Guillermo Del Toro recreates some of its images in his best film, 2015’s Crimson Peak.

It isn’t until 1973 that we get our first unadulterated look behind convent walls. You’ll notice a pattern as we get into the era of full bore Nunsploitation. Each has highfalutin literary aspirations. But none ever seems all that concerned with getting anything like “the facts,“ a hilarious notion in this context, right. Sergio Grieco’s The Sinful Nuns of Saint Valentine claims parentage from a Victor Hugo story, for instance. Maybe the most charming of all the ascriptions is one shared by the first proper Nunsploitation movie, Domenico Paolella’s Nuns and the Devil and Polish hell-raiser Walerian Borowczyk’s marvelous entry Inside Convent Walls from 1978 (the origin of Benedetta’s dildo carved from a religious idol).

Related: Exorcising THE UNHOLY and the Enormous Importance of Christian Horror

Here’s Henri Corinth writing for Mubi Notebook:

“What is more likely is that Borowczyk based his script on a few other sources associated with Stendhal. One is a text written anonymously sometime during the 1570s or 1580s popularly called The Chronicle of the Convent of Sant’Arcangelo at Baiano. This is an allegedly true account of the sexual exploits of Agata Acrimone, Giulia Caracciolo, and Livia Pignatelli, young women from the Neapolitan nobility who were forced to take vows and live in a convent in order to protect their families’ monetary assets.”

Chris Fujiawara comes to the same conclusion in his first analysis of the genre from 1984 in Hermenaut magazine:

“Stendhal found a French translation of a 16th-century chronicle called The Convent of Baiano and was so impressed he reworked the material as an anecdote in Roman Walks and as “Too Much Favor Kills,” one of his Italian Chronicles.”

Certainly we’d seen nuns as figures of furious erotic revision before. The best example may still be Kathleen Byron as Sister Ruth in Black Narcissus by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, who forsakes her vows for want of a man and tries to murder her sister superior for foiling her attempts to get laid. But this is truly an idea best left to directors with no scruples and the Severin boxset is as good a place to look for those completely innocent of scruples.

Related: Severin Films Embracing Nunsploitation With Two Heretical Blu-ray Releases

There’s Images in a Convent by Joe D’Amato, a man who died just before he could rack up his 200th directing credit in the middle of a five-plus-year streak of making almost exclusively porn. There’s The True Story of the Nun of Monza by Bruno Mattei and Claudio Fragasso, the disreputable duo responsible for more than one movie called the worst of all time. Cristiana Devil Nun, also known as Our Lady of Lust, comes in R and X rated versions and is directed by In The Folds of the Flesh’s Sergio Bergonzelli. And then Paolella is represented with his achingly lush follow-up to The Nuns and the Devil, Story of a Cloistered Nun, something like the crowning achievement of the Nunsploitation movement. You couldn’t ask for a better hand.

The interesting thing about this boom is the amount of overlap between the makers and ideas. Paolella made two of the earliest examples (and best) and both featured performances by Martine Brochard (who later wrote a book about miracles after surviving her battle with cancer, a story she shares in one of the many bonus features on the Severin discs). Mattei and Fragasso made their film about the Nun of Monza concurrently with another movie about religious horror, The Other Hell. Fragasso tells a wild story in an interview for Severin about stealing 35mm film from his director of photography to film second unit. The two men wound up fighting with knives and axes lying around the set.

Related: Devil’s Due: 6 Scary Memorable Depictions of Satan On Screen

D’amato’s magnificent later Convent of Sinners was once more loosely based on Diderot’s La Religieuse, except he adds the devil to the mix. And then there the other usual grindhouse misfits like Andrea Bianchi (Malabimba, The Malicious Whore), Franco Propseri (The Last House on the Beach), Gilberto Martinez Solares (La Sexorcista), and José Bénazéraf (Les contes de La Fontaine), who never missed an opportunity to put their stamp on the newest craze. Giuseppe Vari even sent Laura Gemser’s box office sensation/barely legal ripoff Emanuelle (a character stewarded by D’Amato) to a convent in Sister Emanuelle. Everyone got in on the action.

If, however, the Nunsploitation wave never quite grew to the heft of say, the Italian Spaghetti Western, you can chalk that up to impatience on the part of producers and directors, as well as the fact that most of these were at least porn adjacent if not outright hardcore. In order to write a nun movie, at first you needed to class it up with a historical event. Then later you needed to have something the other nun movies wouldn’t. Ken Russell began by having Redgrave picture Reed as a sweating, heaving Jesus whom she nearly mounts on the cross in The Devils. By 1979 D’amato had nuns performing on-camera fellatio on brigands. What exactly else could you do to these poor sinners?

The Japanese were even more cavalier. Their first nunsploitation film was School of the Holy Beast but it sure wasn’t their last. Even though they’d make dozens over the next few decades (many straight to VHS in the 90s) all you could do after the likes of School is go more and more vulgar, because the earlier film was tough to top both artistically and spectacularly.

Related: LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS: Billy Porter Compares His Audrey II to The Devil

Director Noribumi Suzuki has a style redolent of Teruo Ishii and Shun’ya Ito, with excellent disorienting use of space and color, though he never quite ascends to their level. Novitiates whip each other to ribbons while approving superiors look on bemusedly. A Rasputin-like monk rapes one of their ranks. Our hero brings in two horny male outsiders dressed in habits to have sex with her roommate who’s asleep when they start. Students of theological history (or fans of Martin Scorsese’s Silence) will know that Catholics were persecuted when the religion was brought to Japan (around the same time that the stories of blasphemous nuns started making the rounds in central Europe). So a healthy sense of othering priests and nuns also made its way to the 1970s.

The Japanese probably made more nunsploitation movies than just about anyone. An incomplete list of the films that followed School of the Holy Beast includes Masaru Konuma’s Cloistered Nun: Runa’s Confession and Kōyū Ohara’s sequel Runa’s Confession: The Men Crawling All Over Me (both 1976), Yûji Makiguchi’s Nuns that Bite (1979), Ohara’s Sins of Sister Lucia (1978), and Wet Rope Confession: Convent Story (1979), Nobuaki Shiari’s Nun Story: Frustration in Black (1980), Kan Mukai’s Nun: Secret (1978), and Mamoru Watanabe’s Rope of Hell: A Nun’s Story (1981). Each seems more interested in outdoing the last for sheer stunning bad taste (a few of them, like Runa’s Confession, are at least joyfully so).

Related: The Unpredictability of WITCHBOARD: THE DEVIL’S DOORWAY

More so than in Europe the Japanese had been mixing their art movies, their genre movies, and their porn movies without much trouble or compunction since the mid-70s. This allowed Nunsploitation to flourish unabated. They would only be ghettoized with the advent of the home video market. That’s why it might stun some to watch, say, Katsuhiko Fujii’s Nun in Rope Hell (1984) and see lighting and art direction right out of a Shohei Imamura or Masahiro Shinoda movie mingling freely with porny keyboard music and electric vibrating chastity belts.

And yet with all this apparent diversity, these Nunsploitation movies all really only tell one tale: A girl goes into a convent or out of a convent thinking life is going to be one thing, she finds out it’s something else, and she wants to go back from whence she came. A woman is sent to a convent because her parents want her out of the way. Inside the place is even more sinful than she could have ever imagined. She leaves looking for freedom and finds persecution, violation, and death. Lesbianism runs rampant, mother superiors are vindictive witches, men come and go as they please leaving broken hearts and hymens behind them. The fury, the longing, the need to destroy the convent and its order, can really only be felt as deeply if the filmmakers aren’t afraid of showing the lowest depths of Hell the nuns have to suffer through.

Related: Groundbreaking Irish Director Aislinn Clarke Talks THE DEVIL’S DOORWAY

The devil comes to these convents in a hundred ways (sometimes he just walks in, if he’s played by Paul Naschy in El Caminante (1979)). When the women rebel against the orthodoxy like Urban Grandier before them, they do so knowing that their souls and their bodies are at stake. The films are whirlwinds of self-destruction, where thorned corsets hide under each habit and cassock, where the devil wants to impregnate you, where wounded saviors are hidden in haylofts and attics, where love is forbidden and escape seems impossible. To scream, to destroy, to be free of the habit, to cast aside the restrictions of someone else’s version of God, to be out of the Goddamned nunnery (where Shakespeare himself would have put you), a place where faith cannot be nourished; that is the freedom they all chase.

A movie that doesn’t quite fit into this schema is a nevertheless relevant forgotten Italian drama from 1965 called The Possessed, where a woman’s longing turns to perceived madness and the people in her close-knit village want to have her exorcised. This leads to her doing the spider-walk (nigh a decade before The Exorcist) in front of church officials. Perhaps it was to prove them right, perhaps it was just to mess with them. The point is it’s hers, the hysteria, her expression of it, it’s what she feels she still has possession of. That’s what the Nunsploitation movies hint at, at their best. True rebellion is most meaningful after total surrender, right when they think they’ve got you where they want you.

Related: Horror History: Happy Birthday, THE NUN Herself, Bonnie Aarons!

And while it’s tempting to look back on this movement nostalgically, it never went anywhere, really. A movie called The Devils of Monza comes out in 1987, telling the same story in a more measured and less exploitative fashion. Mario Baino’s Dark Waters and Lucio Fulci’s Demonia both put nuns at the center of an ancient conspiracy in the 90s. Abel Ferrara’s cinema was transfixed by the image of the spiritual woman in crisis. And lately nuns have come back with a vengeance.

The big one before Benedetta was probably Corin Hardy’s magnificent Conjuring prequel The Nun (2018). In his interview on the Nun of Monza disc Fragasso tries to say he and Mattei inspired this movie, but it’s quite obvious Hardy’s taken his stylistic cues from Fulci’s City of the Living Dead. (Frankly I don’t think Mattei inspired much more than headaches). There’s also Xavier Gens’ The Crucifixion, Jeff Baena’s The Little Hours, Bruce LaBruce’s The Misandrists, Pollyanna McIntosh’s Darlin’, Darren Lynn Bousman’s St. Agatha, and Mickey Reece’s Agatha. Each era deals with the split in orthodoxy in its own way.

When the Nunsploitation genre was properly coined it was during the 1970s reeling not simply from a momentous generational divide but also from Vatican 2, in which the Catholic Church realized they needed to be a little more broad-minded if they wanted to keep their numbers up. Discipline was on its way out.

Related: Liminal Horror: 10 Movies Lost In Space and Time

Today we’re dealing with the realization that no matter how strongly people believe or disbelieve in the ideas like governments or religious orders, nothing short of a full-scale revolution is going to stop them. This means that semantic arguments now divide people more than ever. Our identities have become precious to us in a way that they weren’t, in the public eye, 50 years ago. When, broadly speaking, the world knows what’s going on, knows about the sex crimes covered up by the church, knows about the ways in which the United States government is ensuring the deaths of millions by withholding health care and COVID resources, to say nothing of refusing to curb the contributing factors to global warming, the things we do know we can change become much more important to us. And in that calculus is the idea of God.

The newest nunsploitation movies hint that what has changed is that God no longer belongs to authorities. Like your gender and pronouns, God is whatever you say it is, whatever you feel it is. Though people can argue with you they can’t take your bodily or religious autonomy in the ways that used to be possible. With luck, true freedom lies in store for us before the climate apocalypse (fingers crossed, anyway). You cannot be made to take the vows and wear a habit. That, in its way, is empowering. I do hope, however, that we don’t ever lose the cultural urge to dump gallons of blood on nuns, even if the image doesn’t have the power it did in the 1970s. The minute Catholic group stops trying to protest our Nun movies, we may truly be lost.

Categorized: Editorials News