Bodies To The Void: ‘Alien 3’ And The Devastation of the AIDS Epidemic

The initial and somewhat purveying response to Alien 3 is one of disdain because, in some ways, of how it handled its characters. Aliens was an audience-pleasing film that took the horror elements of the original masterpiece and added likable and memorable characters and rousing moments of pure 80s excess. Most importantly, by the end of Aliens, Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) found her family. The concept of a Chosen Family is a huge thematic device in films because it reaches out to the outsiders in society. But it also has incredibly deep ties to the queer community, who’ve historically been ostracized not only from society but from their own families.

As RuPaul famously says, “We as gay people, we get to choose our family,” even if it’s under the worst possible conditions, like an alien infestation that left a child orphaned, a marine squadless, and a survivor who, through a cruel twist of fate, outlived her own child. If Aliens ended on a crowd-pleasing and hopeful note that the future could potentially look brighter for its trio (and what’s left of their synthetic uncle), Alien 3 announced that there was no hope; the new world you’re about to embark into does not care about you in the slightest. Ripley’s boo? Crushed. Her pseudo child? Drowned and then mercilessly cut open and put on display.

Also Read: Chronic Illness, Loss of Autonomy, and Aliens in ‘Dark Skies’

Coming out of the 80s, this was also a prevailing sentiment among queer people who were met with an apathetic society, a president who did not want to publicly utter the word AIDS, and an epidemic that killed over 100,000 people. From the moment that a facehugger inserted an embryo that would later burst from Kane (John Hurt)’s chest, the xenomorph has always been about sex and violence. But where the original two films used that motif as a metaphor, Alien 3 was birthed in a generation where sex can equal death and brings that violence to the forefront. It was obvious enough at the time that even Peter Travers commented about it in his 1992 review of the film. But the metaphor goes a lot deeper than a surface-level examination. It imbues the entire film from the visual language to the literal words spoken by its characters.

The easiest point of comparison is actually in the form of Dillon (Charles S. Dutton), the fiery minister looking over his flock of isolated and forgotten men. The language he uses is reminiscent of another fiery crusader who fought against apathy for and in his own community of isolated and forgotten men: Larry Kramer. Kramer was a firebrand who wrote incendiary books titled Faggot and famously wrote “1,112 and Counting”. This essay discussed AIDS, the government’s willful ignorance of it, and the gay community’s relative apathy. In the late 80s, upset with the lack of progress made against the disease, Kramer spearheaded ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a grassroots organization designed to give a voice to a community of silenced and dying people.

Also Read: Not Just Aliens: Why Horror In Space Is So Terrifying

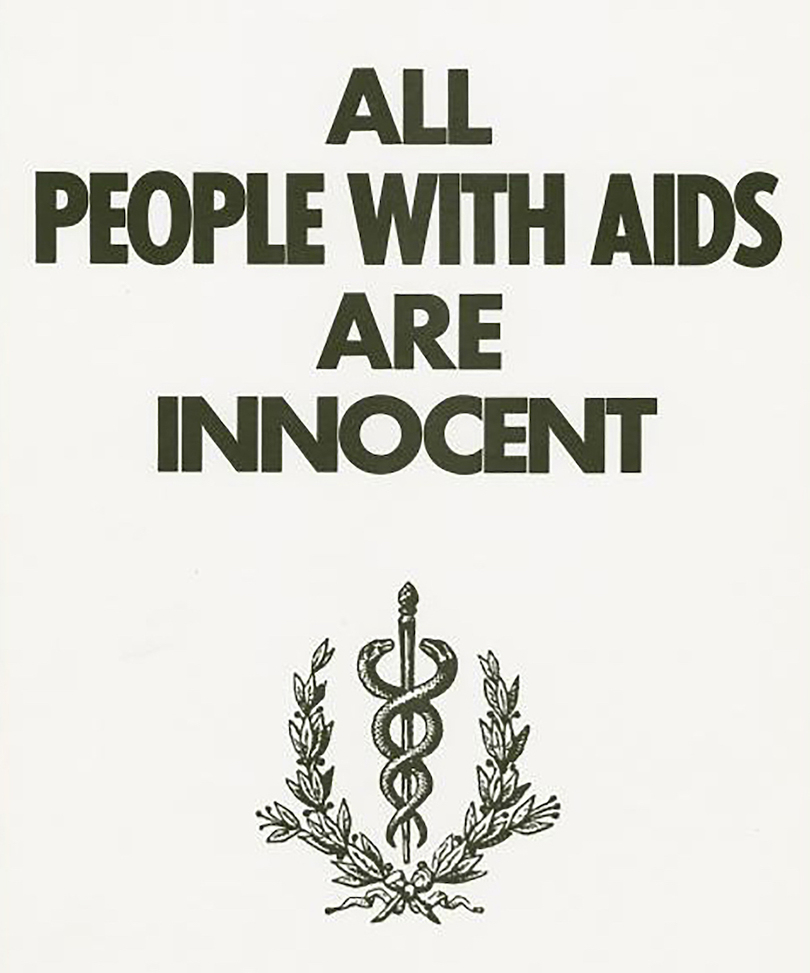

Dillon is first introduced in Alien 3, giving a eulogy for Newt and Hicks as they are cremated. His words take language used in famous pieces of art that spawned from an art collective that came out of ACT UP called Gran Fury. Gran Fury married commercial art with political messages to protest and change society’s perception of queer people and AIDS. While Newt and Hicks are being tossed into the flames, Dillon says, “Why? Why are the innocent punished?” It’s a valid response to senseless death, but it’s also one of the more successful posters that Gran Fury created to raise awareness of AIDS: “All people with AIDS are innocent.” Dillon’s eulogy about innocent death is then juxtaposed with the birth of the alien. It gushes forth from its also innocent host as a reminder of the viciousness of the sex monster that’s a stand-in for AIDS.

But it’s actually later in the film that clued most people with an understanding of queer history and the AIDS epidemic that Alien 3 might be using the xenomorph as a metaphor for AIDS. In 1987, Kramer paraphrased his “1,112 and Counting” article as he gave a speech to a New York group of queer people, and thundered,

“If my speech tonight doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in real trouble. If what you’re hearing doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage, and action, gay men will have no future here on earth. How long does it take before you get angry and fight back?”

Also Read: ‘Aliens’ and a Powerful Clash of the Matriarchies

When everyone is at their lowest in Alien 3 and ready to give up or have a false belief that the Company will ride in and save them, Dillon channels Larry Kramer’s essay and his speech. He tells his own frightened and somewhat apathetic group of men,

“We’re all gonna die. The only question is how you check out. Do you want it on your feet or on your fuckin’ knees…begging! I ain’t much for begging. Nobody ever gave me nothing. So I say fuck that thing. Let’s fight it!”

It’s a speech that not only paraphrases Kramer’s own words, but galvanizes Dillon’s own community, railing at them to not go quietly into the night. No one is coming to save you. Not the government. Not the Company.

You must save yourself.

But Alien 3 doesn’t stop there with the metaphor. Consider the location of the third film, a planet called Fiorina. A place colloquially called Fury 161. On the surface, that seems like a relatively unimportant detail unless you’re familiar with queer iconography in the 80s. The same organization that created the “All People With AIDS Are Innocent” poster created many other pieces of art. And one of the earliest works Gran Fury produced? AIDS: 1 in 61.

In other words: Fury 161.

Also Read: Look At My Beautiful Son: An Ode to ‘Alien: Resurrection‘

Fury 161 itself is visually described as a sick and dying planet. It’s barren and rocky, covered in parasitic bugs and powerful, debris-flinging winds where the temperatures get to -40 at night. It’s inhospitable and it’s isolated; a place where those deemed dangerous to society were sent to be forgotten. It also seems hazardous to the people who call it home. But when the prison colony was decommissioned, the inmates, having found a colony and a society to call their own, decided to stay. While comparing the crimes of murderers and rapists to the infected queer community might sound cringe-inducing, it’s also precisely how the queer community was treated in the 80s, when the so-called “gay cancer” was an unknowable killer.

Queer people were thrown on the streets by their landlords and roommates, ostracized by friends and family, looked at as if they were as dangerous as the felons locked up on Fury 161. And when AIDS patients were admitted to hospitals, many were sent to isolated “AIDS units”, where doctors would wear protective gear and friends, if they actually visited, were kept away. In the later stages of their disease, a lot of hospitals would group the patients on isolated floors where they would eventually die, alone and oftentimes abandoned by their family and friends. Such fate befalls the prisoners at Fury 161, who’ve been left to carry out the rest of their lives on an unforgiving rock of a planet, alone and mostly forgotten.

Also Read: The Alien Report’ Review — A Visually Stunning Found Footage Abduction Stand Out [Unnamed Footage Festival 2022]

For a franchise that’s grounded in sexual imagery, it wasn’t until Alien 3 that Ellen Ripley was allowed some form of physical intimacy. Aside from stripping away her clothes at the end of the original film, the most overly sexual Ripley became was being flirty with Corporal Hicks (Michael Biehn). That all changes in Alien 3, when she aggressively asks Dr. Clemens (Charles Dance) whether he found her attractive because “it’s been a very long time” and she’s lonely. The film juxtaposes Ripley’s request for sex with the film’s first xenomorph-related death, once again mixing sex and violence. It’s only after this moment of intimacy, as the pair lay in the afterglow that the inmate’s death is announced; a proclamation that the contagion has reached the planet that is further pinpointed by the camera focusing on Ripley’s look of consternation, worry, and fear.

Because the xenomorph is a contagion in Alien 3. That choice word is expressly stated by Ripley as a means of forcing Dr. Clemens to initially perform an autopsy on poor Newt. And when traces of the parasite aren’t found, Ripley demands the bodies be cremated, as mentioned above, to curb a possible outbreak. Cremation is often a tool used to fight infection and in the late 80s, researchers discovered that, in New York City, people who died of AIDS were more than twice as likely to be cremated than those who died from other conditions. Unfortunately, after Ripley finally has her intimate moment in the franchise, the shoe drops; not only is the contagion here, but she is also infected.

Also Read: New ‘Alien’ Film In The Works From ‘Evil Dead’ Director Fede Álvarez!

As the film continues, she becomes aggressively weaker. She coughs and holds her chest in pain. The strong and powerful woman who flambéed egg sacs and faced down the alien Queen finds it difficult to do manual labor. Like the alien growing inside her, AIDS is a wasting disease that hollows out its victims. Her gaunt appearance and clothes hanging off her body visually heighten that metaphor.

All of this visual language culminates in Alien 3’s nihilistic ending that leaves virtually everyone on Fury 161 dead. Morse, the only surviving member, is marched off, presumably to his death. As the company arrives in combat gear and, tellingly, hazmat suits, Ripley is unconsciously given a choice. She can go with the medical crew, where she will be prodded and examined and, eventually, invasively operated on to secure the contagion living inside her. Or she can die with dignity. It’s a devastating choice that AIDS patients lived with and, in a lot of cases, wanted in the 80s for a disease that had no known cure. A NY Times article from 1985 examined a similar scenario playing out at NY’s Bellevue Hospital Center, where patients wanted to forgo invasive treatments and, instead, wanted to die with dignity. It’s this nihilistic choice that Ripley makes.

And while Elliot Goldenthal’s beautiful score takes on a majestic and hopeful note, Ripley’s burning body crescendoing into a ravishing climax as the sun crests the forlorn planet, Alien 3 ultimately ends with Ripley, the last surviving member of the Nostromo, signing off. An acknowledgment of the sacrifices made across three films.

And a slight hope for a better future.

Categorized: Editorials News