Queerness and Self-Discovery through The Haunted House

As long as they’ve existed, haunted house films have represented the best and worst of the human condition. Trauma, illness, sin, fear and death; the house, its victims, and the ghostly inhabitants can represent any variation of these things. For myself, haunted house movies have always carried a different meaning. The haunted house subgenre encapsulates every finite aspect of my identity as a genderqueer bisexual who was raised in The Church. They represent the fear of destroying the perfect nuclear family unit, shame, terror, the inability to escape myself, and the eventual acceptance and adoration for my true identity.

In some Haunted House movies, there’s the bisection of The House and The Haunt, separated by circumstance and intention. The House often exists with the purpose of destruction, terror, and dismantling the status quo. The Haunt is often the byproduct of trauma that creates The House. Sometimes a Haunted House exists as an outlet for The Haunt. It’s where spirits, or ghosts, exist to try and maneuver within their own trauma. If The Haunted House represents our queerness, then The Haunt represents the trauma we suffer while we attempt to navigate our identities. Whether that’s religious, familial, or societal, it’s the thing that stops us from moving on to the next plane of our own existence, embracing who we are, and finding our own strength and growth from it.

On Halloween 1999 my parents decided that my siblings and I had to stay home. The Church had gotten into trouble for having a costume party the year before. So trick-or-treating wasn’t something other Christian parents were doing. Instead, my mom had us turn out all the lights in the house while she taped a “No Candy” sign to the door, and ushered us down to our basement TV room. Just this once, she had said, because it was Halloween, she would put on a scary movie. We sat in the darkness, munching on popcorn, and watched as the Freeling family came to the conclusion that their house was haunted. Poltergeist is one of the first haunted house movies I can remember watching, and one that stuck with me long after we finally turned the television off.

For some background, my family converted to Evangelical Christianity in the late 90s. Prior to that, my parents were a couple with five kids. They were struggling to get by, working through their own trauma, and sometimes dabbling in the occult. My mom used to do pro bono tarot readings for friends and family. She still does them on occasion for old friends. These might not seem like significant details. But by the mid to late 90s, Satanic Panic had once again reared its head in the church. Hypersexualized pop stars like Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera danced across MTV. Buffy was slaying vampires with her lesbian witch best friend. Harry Potter was the number one kids’ book series. Everywhere, Evangelical parents were convinced that Satan was trying to corrupt their young children.

My liberal and agnostic-raised parents were trying to course-correct our upbringing with their new faith, while also allowing us to keep some of our freedom. This meant things like anime was okay to watch, but MTV was not. Harry Potter was fantastical enough that it was allowed, but Buffy was out. For reasons I will never understand, my older brother was allowed to watch South Park. We lived in a constant state of twisted truths. We were a good Christian Family with South Park Fridays, where Ninja Scroll was safe for consumption. But we weren’t supposed to tell others, especially when I had friends who had been “exorcized” by evil spirits for liking Sailor Moon too much.

By this time I had come to the conclusion that I liked girls, a lot. And not in the traditional friend kind of way either. It had never been a problem before, and my parents had never brought it up as being anything other than normal. But in the circles I was in, murmurs and whispers from concerned parents had traveled to my young ears. So I knew that it was a secret I was supposed to keep.

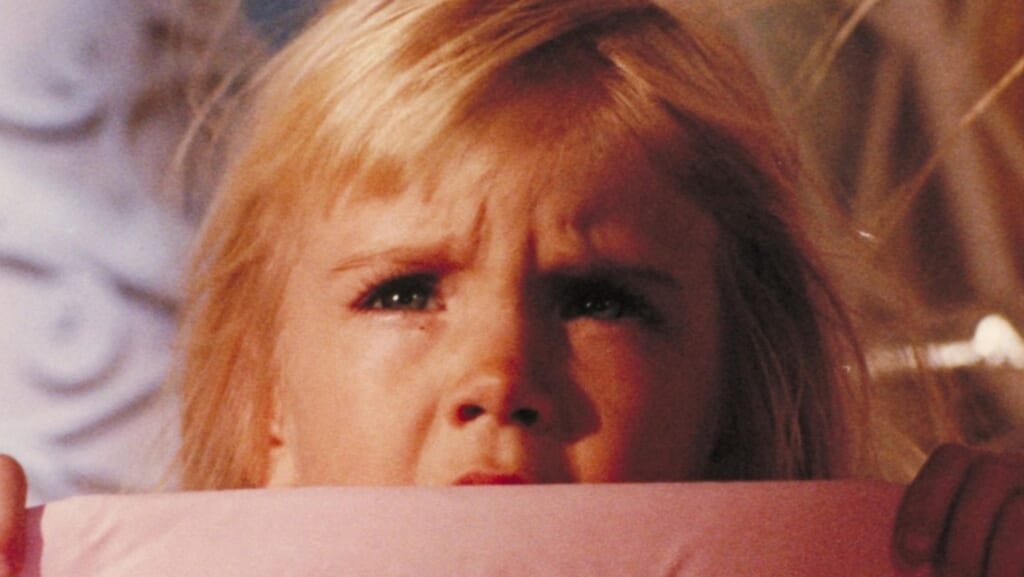

As we watched the Freeling family try and bring their daughter, Carol Anne, back from the depths of the afterlife, I couldn’t help but feel anxiety for her. That her innocent desire to connect with the ‘TV People’ had stolen her innocence, and worse, made her a victim to the allure of the Devil himself. I was captivated by their struggle, and was horrified to find that saving Carol Anne wasn’t the end of the Freeling’s troubles. The Devil came back for them himself, hellbent on punishing their family for the sins of Carol Anne’s curiosity.

There was so much about this family that felt familiar— the desire to maintain a family unit, the pain of having their dream home, and their life, completely uprooted by otherworldly forces, and Carol Anne’s late-night chats with “TV People”. I became quietly obsessed with the Devil coming to collect on my sins, destroying my family in the same way that it had destroyed Carol Anne’s.

This only became more relevant as I continued to watch horror movies. I watched families inhabited homes that represented second chances after being adrift for so long, only to have a child drag them into the sometimes literal depths of hell. To me, the hauntings were my queerness, a way for the Devil to get in. Every seemingly harmless connection could be another way for the devil to take root, and destroy our nuclear family. A chance for me to go from something pure and godly, to something dark, and demonic.

When I see movies like 1978’s The Amityville Horror I feel for Amy, the daughter who begins talking to “Jody”, the demonic entity in the home. In many ways, I was, and am still scared that I will be the Amy of my family. That I’ll bring home my own Jody to haunt and destroy the family life that my parents dreamed of us having. That a relationship will be enough to tear a family apart, to break down a family that has already been weathering the storms of life together.

The reality is that for many of us, our queerness doesn’t get expressed in that kind of outwardly destructive way. Those of us that have grown up sheltered, and closed off, with queerness brought to the forefront as the greatest tragedy to our family units. So we keep it a secret. Our experience, and the way it haunts our lives, is less like a demonic poltergeist uprooting the home and destroying our families, or the possession of rage like Amityville. Instead, it’s a quiet acceptance of our own lack of belonging. It’s a haunting built out of grief and a desire to be set free.

For many of us, our experience aligns closer to The Orphanage. Where Simon’s discovery of his truth leads him to run away, and for the haunt to begin. Not because the Devil stole Simon away like Carol Anne, or because of a vengeful possession like in Amity. But because Simon’s truth was too much to bear. His mother didn’t hear his pleas before it was too late, and his childhood was over. Too many of us struggle with our own identities, abandoned, either because of our own fears, or because of the reality of our familiar situations, left until the haunt becomes too loud, too obvious for the people in our lives to ignore.

Much like Simon, my solution was to run away. In 2008 I moved across the country to attend film school. I got as far away from my family, and church, as possible. It was there that my love of haunted house cinema flourished as we critically watched films like Suspiria, Rosemary’s Baby, and even Paranormal Activity. I also began consuming more Asian horror, obsessively watching movies like The Ringu, Ju-On, and Bunshinsaba. I was fascinated by the concept of a haunted house punishing anyone who entered, regardless of their reasons, good or bad. The destructive nature of the spirit, even though it was usually created out of love, or desperation, was for their own family.

In these movies the spirit is lashing out, taking down any and all entries into the home without any kind of interest in who or why they are there. In many instances, there’s a moment, when we as an audience think that the haunt is over, that the protagonist has managed to overcome the evils of the spirit, that their love or redemption of their tragic death is enough to reverse the curse. We sigh in relief when Sadako is found in the well in Ringu. We think being heard is enough. When Kayako’s murder is solved in Ju-On we hope that that is the end, but it never is. The haunt doesn’t care about the intentions or the understanding of what happened to bring them where they are. They attack, kill, and destroy without prejudice.

This experience is synonymous with my experience as a newly freed college student. While attempting to maintain my purist beliefs, and struggling to grapple with my queerness. I lashed out at anyone who got too close. I was panicked by my own existence. It’s as if I was horrified to discover that I was becoming the thing that I kept fearing. I was living, for the first time in my life, as a queer woman in a relationship. I was doing my best to hide it from my aunt who I was living with, my parents back home, and the outside world.

Much like the ghosts in those films, I didn’t care if the person hurt was the creator of my pain, or simply someone who was trying to help me heal. It culminated in a text-message breakup when I returned back home. It wasn’t just because I didn’t think I could do a long-distance relationship. I wasn’t ready to come out to my parents yet. I injured her without cause, seemingly for simply taking a chance in seeing something in me that I couldn’t see in myself.

Often in our queerness, we become closer and closer to becoming that which we have feared. We go from fearing the haunted house, and its corruption of us and our families, to becoming part of it. The thing that haunts the home, that walks aimlessly through hallways, and lashes out at those that wound us, or those that have the misfortune of crossing our paths as we try to return to our own normalcy. These days, I view these movies through the lens of wanting the house to win, of wanting the haunt to overcome—not only the protagonist, but the circumstances that created the haunting in the first place. To rise above the tragic events that created a vengeful spirit. To find autonomy and peace, a sense of self in the realm of the dead.

In my late 20s, I had taken time off of work to handle my deep depression. I was no longer attending church, and was struggling with accepting who I’d become. In many ways, I felt like I had come full circle, terrified again of the house, the same kid that was fearful of giving into the darkness inside of me that wanted something I didn’t understand. During this time without work, I spent a lot of time watching horror movies. I was on an anti-anxiety medication that had completely dulled my sense of fear, and watching them became a relaxing exercise in film critique. I would curl up in the dark in bed with my cell phone, and watch horror movies before falling asleep. Some of my favorite films to watch were Crimson Peak and Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House.

The first time I watched Crimson Peak, I felt disappointed. I didn’t understand how it was considered a classic gothic horror, when to me, it seemed more like a love story, with the addition of a haunted house to add drama and false stakes. Some of that, I still feel is true, but I think del Toro’s story holds much more depth than that. The house is doing its best to keep Edith Cushing safe, to warn her of the dangerous plot between the Sharpe siblings. The house is Edith’s red flag instinct, her discomfort with the Sharpes. It’s as much a part of her as anything else. Once she embraces the truth of the house, and the haunt, she’s able to escape a damning relationship that ultimately is only meant to lead to her death.

There’s freedom in accepting the haunted house as an extension of the protagonist’s experience. In The Haunting Of Hill House, the Crane siblings have to return to the scene of their childhood trauma, to the house that led to the deaths of their sister and mother, and the beginning of all of their issues. While the house doesn’t lose its malevolence in Hill House, it instead becomes a kind of consuming beast. It takes those that are lost and envelops them in a fantasy of their desires. Every person who ignores the house becomes a victim of its allure.

n a lot of ways, I think this is also similar to the final stages of acceptance within ourselves. In order to come to terms with the thing that, for me, I feared the most. I had to be okay with allowing it to “consume” the life I thought I was supposed to have, the roles I was supposed to play in gender and in spirit; the quiet demure demeanor of a good church wife and daughter. I had to let it masticate, and take the nutrients I could from it in order to come out the way I am today. I’m a more balanced version of myself, who understands that faith and religion aren’t equals, and that my queerness doesn’t make me an obstacle to overcome, or a target for the devil.

When Nell said, “I learned a secret. There’s no without. I am not gone. I’m scattered into so many pieces, sprinkled on your life like new snow”, I realized that is a lie that we tell ourselves, that accepting who we are, means losing who we were. But that’s not the case at all. We just continue to be, to change, to no longer live in fear of the haunted house that is our queerness. We are able to be proud of the discovery of who we were, who we are, and who we will become.

Categorized: Editorials News