‘We Are Still Here’ And Its Chilling Depiction of Depression In The Dead Of Winter

The opening scene of We Are Still Here is a quiet series of static shots of a snow-crusted landscape. The wind whistles across the countryside, and the snow drifts with increasing severity. The frigid temperature seems to seep from the screen, and the viewer immediately plunges into the dead of winter. Director Ted Geoghegan meditates on winter’s mercilessness in a way that sets the tone for his exploration of depression and grief. We Are Still Here is as much about the cold as it is about one woman’s mental deterioration and eventual acceptance of her son’s death.

A zest for life has faded from Anne’s (Barbara Crampton) face. Her son died only a few months ago, so the pain and misery are still red and swollen. She walks, zombie-like, through her life, and hope appears nowhere on the horizon. Along with her husband Paul (Andrew Sensenig), the couple relocates to a secluded home in the middle of rural New England. Despite the impenetrable cold, Paul is hopeful that a change of location is exactly what his wife needs to shake her depression. But it’s not likely to do any good. The cold wraps its gnarl hands around her throat, exacerbating her inner turmoil. Winter is always the longest and the hardest. The days have grown short, and the clouds have turned the earth into a gray washed-out canvas full of dead things.

Whether you’re suffering from seasonal affective disorder (or SAD) or clinical depression or grief, or a mix of all three, winter is the toughest time of the year. It settles on your shoulders and refuses to let up. It’s hard for those who don’t experience depression to fully grasp what it’s like to live in the shadows. As Dr. Paul Desan, a psychiatrist at the Yale School of Medicine, notes, “People may not appreciate how severely someone who has SAD is affected. Their life just shuts down for half the year.” Typically, SAD starts in late autumn and early winter and lasts several months, until spring breaks through the atmosphere. For Anne, her depression has been triggered by the death of her son, and the winter months prove to be detrimental to her well-being in every conceivable way.

Settled into their new home, Anne and Paul are visited by two neighbors, who seem congenial enough but a little off. Dave (Monte Markham) shares a story about the history of the house and how the original tenants, the Dagmars, once sold corpses to a university in Essex. They were subsequently run out of town, and Mr. Dagmar killed himself soon after. It’s been 30 years since the house has had “fresh souls,” Dave says, “It needs a family.”

Paul brushes off Anne’s concerns as “weirdness,” much to her dismay. “I still feel something here,” she says with a crack in her voice. To uncover answers, Anne invites her clairvoyant friend May (Lisa Marie) and her pothead husband Jacob (Larry Fessenden) up for the weekend. Anne hopes to conduct a seance to reach out to the other side, fully believing her son Bobby to be present in the home. But as May later warns, she doesn’t feel Bobby’s presence at all. Instead, a dark malevolence blankets the space. “You can’t give Annie all this hope and then not deliver on anything at all,” Paul pleads, to which May retorts, “We don’t need to find the darkness here, Paul. It’s everywhere.”

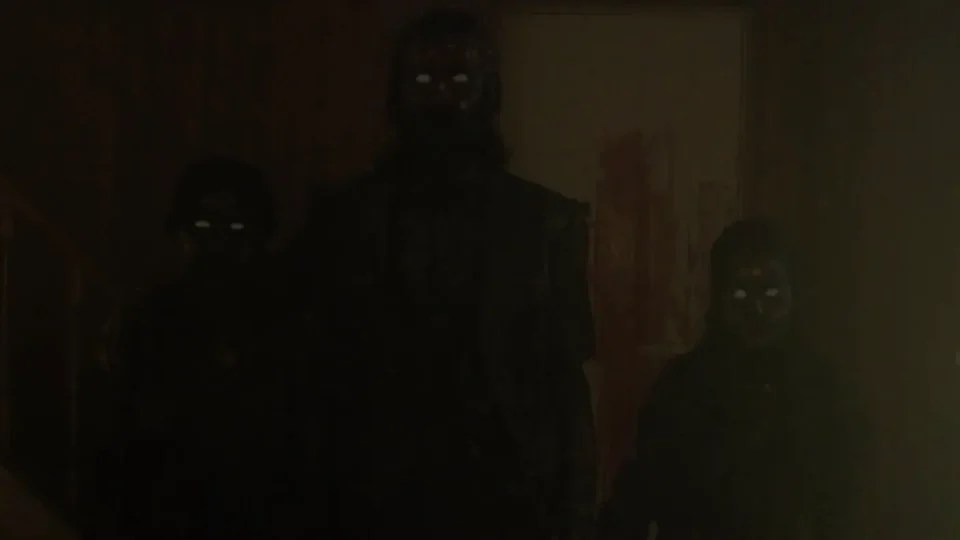

Charred demons walk the premises. These poor, lost souls come to collect on sacrifices promised through a decades-old pact with the nearby town. Dave and the other villagers live in constant fear and believe that one day it might all come undone. The demons’ presence is initially marked by the overwhelming stench of smoke. Thinking it to be a problem with the boiler, Paul hires an electrician, who becomes the first of many victims the demons attack. Their ever-present nature claws at Anne, as a manifestation of the shroud of depression that hangs over her life. Geoghegan frequently reminds the audience of this through numerous b-roll shots of the exterior of the home, with the winter wind howling and the snow swirling in menacing patterns. It’s a claustrophobic feeling and presses upon the viewer with bludgeoning force. Demons plague her mind, and the cold savagely torments her. Anne can’t escape.

Anne is representative of the nearly 10 percent of people in the U.S. who suffer from seasonal affective disorder. For many, it’s the changing of the clock that knocks circadian rhythm off-track and results in tiredness and pendulum-like fluctuations in weight, among other vital signs. As Hannah Seo reports for The New York Times: “Most people who are vulnerable to SAD are most likely always susceptible to feeling down, said Kathryn Roecklein, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Pittsburgh. But in the winter, light levels fall below a threshold and suddenly things are off balance.”

In her grief, Anne succumbs to winter’s frigid clutches. Her mental state declines and even Paul believes her claims that Bobby is still with them to be simply delusions. That leaves Anne to fend for herself (at least initially). Bobby’s death and her depression then make her vulnerable to the demons’ advances. With each passing minute, they draw closer and closer一but in truth, they don’t even want to kill her. As we learn in the finale, the demons are a reminder of her soul-crushing anguish, embodiments of the darkness oozing out of her brain.

After Jacob and Paul perform a seance against May’s wishes, all hell breaks loose. Literally. The demons emerge from the basement and pounce on their prey. Led by a shotgun-toting Dave, the villagers come to sacrifice Anne and Paul to the house in the hopes of continuing their sacrificial contract. They have another thing coming, however. The demons set their targets on the townsfolk instead, ripping and tearing their bodies to ribbons.

During the bloody commotion, Dave delivers a series of lines that cut to the bone of the film’s thematic center. “You stay. You satisfy the darkness,” seethes Dave. “And why would you want to go and leave your little boy here all alone. Don’t fight it. Just accept it.” He gazes for a brief moment upon the wreckage nearly swallowing them whole. “You see what happens when you try to fight it,” he says.

Within these words, there lies Anne’s entire arc in the film. She’s a broken woman trying to wade through the watery depths of grief and mental illness. The gnawing inside her body is cruel and harsh, as it eats away at her very being. Paul eventually comes around to believing her claims, yet it’s entirely her weight to bear. It’s only through reaching the darkest and most sorrowful place in her life that she rediscovers herself and the strength long lost and buried. Her mental illness won’t be cured so easily, but through acceptance of death, she is able to save herself from a terrible fate.

We Are Still Here is far more than a simple ghost story. It displays the ravages of mental illness in deep winter with great care about Anne’s humanity. Ted Geoghegan comments on both grief and depression, making such an intensely personal story feel universal, as though we are all bound together in the human experience. With a driving emotional core, and a reliance on haunted house conventions, the film brilliantly captures the raw truth about living and dying. And try as we might, we can’t escape any of it. Why would we want to anyway.

Categorized:Editorials News