Rage Against the Machine: ‘Take Back The Night’ Tackles Rape Culture

Take Back The Night is not your typical rape revenge movie. Co-written by director Gia Elliot and star Emma Fitzpatrick, the film follows Jane (Fitzpatrick), a visual artist and influencer who demands justice after suffering a horrific sexual assault. As her name implies, Jane could be any victim of this all-too-common crime. However, Jane’s story is unique. We never find out the identity of her attacker and never even see a face. The film’s true villain is the system itself: the police force she turns to for help and the media machine that uses her trauma for headlines.

Without a clearly identified rapist, Elliot’s film becomes a scathing critique of the revictimization many rape survivors experience after reporting assault. Take Back The Night does not code its message and may work better as an allegory than a cohesive narrative. However, the film’s strength lies in its unflinching honesty. By boldly depicting the horrific aftermath of sexual assault, Elliot exposes the massive failure of a system designed to punish rather than to heal.

Take Back The Night begins with a typical night out on the town. Celebrating a sold-out art show, Jane drinks a little too much at an after-party and hooks up with a stranger in the bathroom. While walking home, she finds herself trapped in an alley and is sexually assaulted by a shapeless monster. Dirty, bruised, and bleeding, Jane stumbles into an emergency room and reports the crime. After the grueling examination, she returns home and shares her story over social media.

Also Read: ‘Teeth’ and The Anatomical Possibilities of Vagina Dentata [Science Of The Scare]

Family, friends, and followers are at first compassionate, but as the days go by, sympathy for Jane begins to wane. Her sister (Angela Gulner) becomes frustrated with the way she chooses to recover and the police use details from Jane’s past to blame her for the crime. Continually stalked by the enigmatic rapist, Jane is also tormented by a culture more interested in preserving the status quo than admitting its own faults.

Scenes in Take Back The Night depicting Jane’s attacker are horrific. Appearing as a formless black void, the rapist is simultaneously everyone and no one; a personification of sexual predation. However, the film’s true horror lies in the moments when Jane is supposed to be safe. She arrives at the hospital and undergoes upsetting examinations. Not only do strangers take multiple pictures of her beaten body, but they poke and prod her wounds, roughly comb through her hair, and swab her insides to collect samples for a rape kit. Jane must recount her story during this ordeal and everything she says is taken as fact despite signs that she may be in shock.

While this hours-long process would be worthwhile if it helped catch the attacker, she later finds out the nightmare is essentially meaningless. Hers is one of the thousands of rape kits sitting on a shelf waiting to be processed. Unless she can convince police that her case is worth pursuing, the department will not waste time and resources investigating the physical evidence she so painfully gave.

Also Read: ‘Savage Weekend’ And The Unapologetically Queer Nicky [The Lone Queer]

When Jane returns home, she makes plans to go live on Instagram. Broadcasting to her many followers, she tells the story of her attack and shows her wounds including a crescent-shaped gash on her wrist. Attracting the attention of a local reporter (Sibongile Mlambo), Jane accepts an offer to tell her story on live TV. She wears her favorite dress which happens to be the same design she was wearing when she was assaulted.

Her sister calls the garment inappropriate and hints that this simple assembly of cloth has become a symbol of who Jane was at the time of the rape. Though she doesn’t go so far as to suggest Jane’s appearance caused the crime, she does imply that this version of Jane has been forever ruined. The decent thing to do is abandon her preferred self-expression. By defiantly wearing this dress, Jane is reclaiming a piece of her identity. She refuses to let her attacker change a fundamental part of who she is.

Her sister’s response is a common one. We have been conditioned to expect survivors to feel shame and embarrassment in the aftermath of rape. While there is no right or wrong emotional response to this type of extreme trauma, many survivors feel responsible and our society is all too ready to blame the victim. Rape culture is the internalized belief that sexual assault is an unavoidable part of female life.

Also Read: 5 Disturbing Queer Horror Films To Keep You Up At Night [New Queer Extremity]

We assume that those who have not experienced it have done something right and that victims have failed in some way. We learn to dress defensively, to thread our keys through our fingers, and to avoid dark alleys to protect ourselves from a crime we treat as inevitable. Any deviation from this protective behavior is viewed as an invitation for rape. But Jane refuses to accept responsibility for what happened to her and she will not hide in shame that implies she did something wrong. By telling her story and demanding justice regardless of her own actions, Jane confronts a toxic system that blames women for sexual assault instead of trying to prevent it from happening.

Unbeknownst to Jane, the reporter who interviews her has unearthed a family history of mental illness. She confronts Jane with her painful past live on the air, orchestrating a “gotcha” moment intended to boost her own ratings. After she publicly discredits Jane, followers begin to turn away as well. Many who once offered support now accuse her of lying for attention. The wife of the man Jane slept with at the party comes forward and smears Jane’s character, implying that a woman who would sleep with a married man is not worth protecting. Jane is an imperfect victim and the collective public finds it easier to reject her story than to confront the larger problem her attack exposes.

Also Read: ‘Calvaire’ and Horror in the Absence of a Matriarch [Matriarchy Rising]

As Jane continues to speak out, the detective assigned to her case (Jennifer Lafleur) turns against her as well. Not only was she drinking and doing drugs on the night she was raped, but she has a history of mental illness and a criminal record. Though Jane’s past has absolutely nothing to do with a random attack, this detective uses these perceived flaws as an excuse to question her story. It’s worth noting that this female detective is likely facing immense pressure to prove herself in a man’s world. It would be much easier to close this complicated case by rewriting the narrative and blaming Jane.

Her attitude is unfortunately common and indicative of a criminal justice system that cannot function without a criminal. With no suspect in sight, Jane falls into the line of fire and each interaction with law enforcement brings with it flashbacks of the rape. The monster appears behind her in the interrogation room and grasps her shoulders while the detective peppers her with aggressive questions indicating that the trauma Jane suffers at the hands of the police has become another element of the rape.

Also Read: Big Ass List of Women-Directed Horror

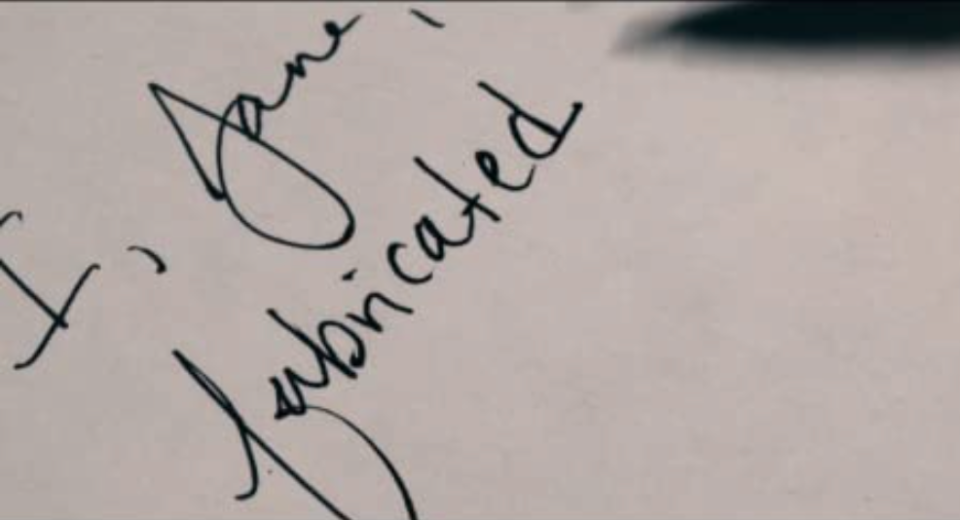

When Jane can’t explain slight inconsistencies with the report she gave at the hospital, the detective threatens her with criminal charges. Insisting that she actually was attacked, Jane offers to take a lie detector test rather than recant her story. We then listen to an unseen man deliver a horrifying line of questioning solely focused on Jane’s own character. The man does not ask her anything at all about the attack and heavily implies that she caused the wounds herself. The film begins with audio from this line of questioning as we watch Jane walk through a busy subway station. Obviously in distress, she walks to the platform and prepares to throw herself in front of a train. The juxtaposition of questioning from the police and Jane’s attempt to die by suicide explicitly shows the revictimization so many survivors suffer at the hands of law enforcement.

In an interview with Rue Morgue, Elliot described observations of court proceedings saying, “The way that the intake questions are written for survivors basically ignores any sort of psychology. They do not account for the way that your right brain and your left brain stop communicating which then impacts how memories are stored.”

Also Read: ‘Scary Movie’: A Tribute to Regina Hall as Brenda Meeks

Unsurprisingly, Jane fails the test and is essentially forced to recant her story. Even more frustrating, a third-act twist reveals that the detective bears a crescent-shaped scar on her own wrist indicating that she is a survivor as well. She knows Jane is telling the truth because she has encountered the same monster. Perhaps she feels so much shame from her own attack that she responds with anger when Jane reminds her of the trauma she’s tried to forget. It’s also possible that she’s frustrated with herself for not speaking out like Jane. Though the detective does eventually change her mind, all of her official documentation has gone into discrediting Jane’s story. The damage has been done.

The opening scene of Take Back The Night leaves Jane’s fate in question, but a second trip to the subway station reveals a more hopeful conclusion. A stranger reaches out and pulls her back. This unnamed woman looks directly at Jane and says, “I believe you” and it’s enough to emotionally rescue Jane as well. Comparing Take Back The Night to #MeToo, Elliot describes the movement as “strangers finding each other and backing each other up.” She resisted identifying this character in the crowd, intending to represent the millions of survivors sharing their stories with each other and drawing upon a well of invisible support.

It’s at this point that the tone of Take Back The Night changes. Women with the same crescent-shaped scar begin to come forward and share their own stories. They not only describe this centuries-old monster but share ways they’ve found to combat it. Supporters begin to draw crescents on their own wrists and publicly announce their support. They call themselves Jane’s army, referring to the film’s main character, but this name is no coincidence.

Also Read: The Everlasting Wonder of ‘Orphan Black’

Jane Doe has long been a pseudonym for women and female-identifying people who report sexual assault and wish to remain anonymous. Perhaps they fear the pain we see Jane experience or maybe they simply don’t want details from the worst day of their lives open for public debate. By identifying as a member of Jane’s Army, these strangers are not only declaring that they support Jane, but all survivors of sexual assault. And by fighting for herself, Jane is fighting for us all.

Jane’s message is simple: monsters are real. As we watch the film and find the nebulous attacker reappearing every time she interacts with the police, we realize that the actual beast is rape culture itself and a system woefully uninterested in combatting it. Jane becomes every person who has ever reported sexual assault only to later wished they hadn’t; every victim who turned to the police for help and found their suffering compounded. Take Back the Night may deliver its message with a heavy hand, but it’s one worth shouting about. Rape culture is real and the pain it causes is worth preventing. Elliot named the film for a decade-spanning movement of people who insist that we should not have to go through life dodging predators. We’re not lucky every time we get home safely. We are the victims of a culture that sees our safety as expendable.

Also Read: Victoria Pedretti is the Soul of ‘The Haunting Of Hill House’

We have collectively become so accustomed to sexual assault that Jane’s story no longer feels shocking. What feels novel is Jane’s refusal to blame herself for the crime. By demanding justice, Jane reveals the extent of a broken system. She tells her followers that the monster who attacked her is still out there. And she’s right. Every time we make life difficult for people reporting rape, we make it less likely that the next person will come forward. And by looking for ways to discredit survivors, we become a part of the crime itself.

Categorized:Editorials News