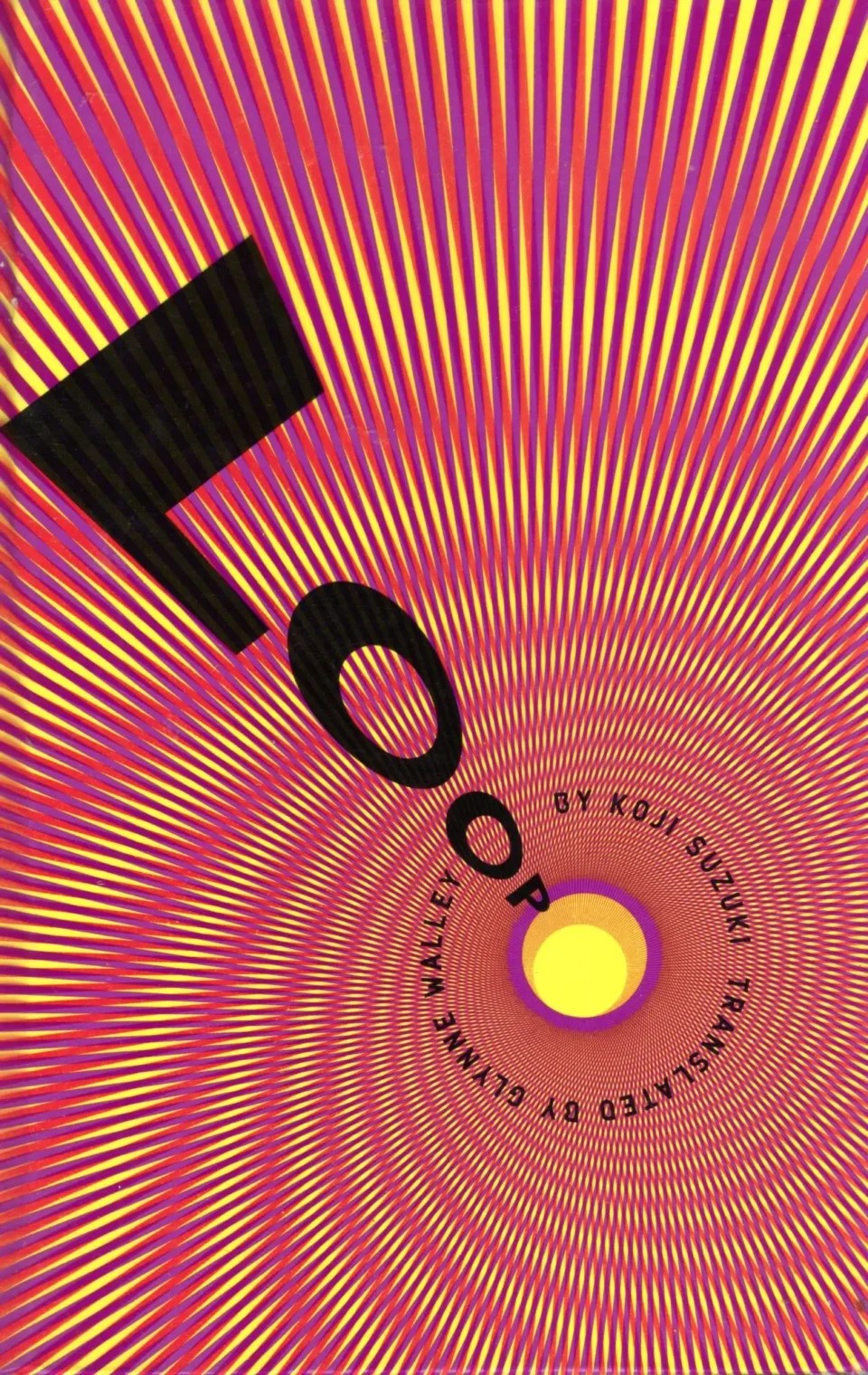

Koji Suzuki’s ‘Loop’: The Third ‘Ring’ Novel Is A Universe Unto Itself [Abibliophobia]

Welcome to Abibliophobia, the monthly column where Katelyn Nelson digs into the connections and influences buried deep within the world of the written word and its far-reaching tendrils across media. Focused broadly on horror and the ways it sneaks among the pages, each month will explore a new book or series and its impact on our culture, through the lens of history, the relationship between film and literature, and what varying adaptations have to say about how we understand and recreate stories. So curl up by the fire and crack those dusty covers open. We have a lot of exploring to do.

Over the course of digging into Koji Suzuki’s Ring series, I’ve thought a lot about how different kinds of adaptations affect things like the transmission of a message, and how best to keep the full impact of that message as concentrated and accurate as possible. In our first introduction to Sadako and her brutal death, we piece the story together from all kinds of hearsay and justification for heinous actions, even as we have already gotten the truth as directly from the source as possible—psychic imprints from Sadako’s own mind and eyes onto a videotape destined to kill anyone who watches if they fail to spread the curse to another.

Also Read: Predatory Evolution in Koji Suzuki’s ‘Spiral’ [Abibliophobia]

More than just killing, though, every iteration of the films in the—now quite hefty—Ring franchise kills with fear brought on by direct eye contact with Sadako herself. If you will not spread her story and her rage, you will die facing her fury directly, unable to look away as she goes beyond victimhood into vengeance.

With the introduction of Spiral came new layers of potential and meaning. Sadako’s curse manifested beyond a simple video tape into an actual virus. A virus whose visual genetic makeup startlingly resembled a ring. That mimicked the very virus she herself was exposed to via her rapist: smallpox. Meanwhile, there is also a great deal of talk about secret codes and medical terminology and genetic makeup and how appealing pieces of a person’s body are.

We are introduced to Ando, who is perhaps the most emotionally driven man to date in the trilogy, racked with grief over his son’s tragic death and willing to do anything to fill the void left behind as a result of it. He is the first man in the series to admit to falling in love with a woman he believes to be Ryuji Takayama’s former girlfriend Mai Takano. And she is…at first. Until she isn’t.

Also Read: Koji Suzuki’s ‘Ring’: A Deeper Look At Sadako’s Rage

Until Sadako finds a way to claw herself back into the real world and continue her quest in as physical a way as she can manage. Through some rather manipulative techniques of her own, she presents herself to be Mai Takano in a night of passion and, ultimately, gets pregnant by Ando. Strange, though, that the reveal of her true identity should come because she once again exposes her body, and her intersexuality dawns on Ando amid much horror and confusion. All the while, her curse threatens to spread in an even more rapid fashion as the novel form of Asakawa’s discoveries goes to print.

After the events of Spiral, we are taken in what at first appears to be a wholly new direction with almost no connection to anything we’ve seen thus far with 1998’s Loop. We’re introduced to Kaoru, a precocious ten-year-old with a vicious hunger for knowledge of the world and its origins who frequently debates things like longevity zones and the existence of a god with his scientist father. Beyond simply understanding how the world works, he craves an understanding of how it, and we, began and how it, and we, can continue.

Also Read: Conversations on Obsession in ‘Perfect Blue’

When his father contracts a particularly vicious new cancer that slowly robs him of each organ and regular body function, Kaoru and his mother take distinctly different approaches to pursue a cure. His mother, who has a degree in literature with a concentration on American culture and Native American folklore, seeks answers in texts that describe things like mythologies of immortality and longevity in communion with the gods. Kaoru, meanwhile, turns to studying medicine—including the cells of his father’s own cancer.

Cells, it is worth noting, which he describes as resembling “somehow feminine…egg-shaped faces with smooth, almost slippery skin”. Over and over the same face repeats in the cells for what is known as the Metastatic Human Cancer Virus, which can lay dormant in a person for years at a time before making its presence known by causing all your organs to fail, one by one. Kaoru reckons bitterly with the idea of mortality at the hands of something which can duplicate itself in perpetuity, essentially an immortal thing sapping life from humanity and the world around them alike.

Also Read: Queerness and Disability in Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone

Kaoru’s interest in longevity zones led him to discover an area of North America that has a particularly strong longevity zone, with particularly low gravitational force resembling on a map—you guessed it—the depth of a well. As a child, Kaoru extracts a promise from his father to go there as a family to investigate, soon after which his father is diagnosed with the MHC virus. For the majority of the novel, Kaoru is 20 years old, haunted by this place he felt had all the answers his heart desired, ripped out of reach by a virus no one in the world can wrap their heads around. The MHC virus wipes out thousands before they even begin to understand how it functions, and millions before they even begin to fathom how to develop a vaccine.

If all of this sounds like the medical side of Spiral turned up to 11, you’re right! But even that hardly scratches the surface. Kaoru’s father, after all, was a scientist on a virtual reality experiment known as the Loop, which aimed to explore the idea of developing artificial life and creating a virtual world close enough to our own to help us predict and avoid problems in the real world. Naturally, this experiment both ran out of funding and failed spectacularly when the AI world became cancerous and all diversity that had originally developed fairly organically was wiped out in favor of continuous replication of the same genetic template. Not to mention, everyone involved with the project is dropping with alarming speed at the hands of the MHC virus. What’s that, in the distance? The sound of Sadako laughing her way to revenge in two worlds at once?

Be warned that from this point on there are hefty spoilers for Loop’s twisty reveal.

Loop is, unsurprisingly, the only novel in the trilogy to have never been adapted. It is also the densest to read, in some ways. There is an incredible amount of talk about mortality vs immortality and the construction and death of virtual worlds. An entire undercurrent debate on the existence of God versus the probability of chance. Ideas about the potential future steps of human evolution that might bring us one step closer to immortality, and yet more debate on just what the qualifications are for something to be considered truly real.

In 283 pages, Suzuki creates such a mind-bending playground to explore, with so many threads dancing on either side of the veil, that it almost shouldn’t work at all. Kaoru’s true origins—that he is, firstly, adopted and, secondly, the result of an experiment to bring Ryuji Takayama out of the virtual world in which he died and out into the real—probably should not make any sense whatsoever. And yet, in Koji Suzuki’s hands, thanks to seeds that were planted all the way back in Spiral, it does. Kaoru is revealed to be Ryuji Takayama reborn, and we buy it. What’s more, it contributes to a discussion on reality and humanity the novel has been stewing on the whole time in a way that is equally as rewarding as it is horrifying.

Also Read: ‘Smile’ Is A Scarier Version Of ‘The Ring’

Here we sit, in the year 2023, three years into a pandemic that is still ravaging the population of the world in waves at a time whose effects we are still uncovering, trying to find a way to dance the line of safely navigating the world and watching startling technological developments at the hands of people who, while they do not seem to want to play god just yet, certainly seek to rip away both creative and personal autonomy. Hell, the most recent phone scam is one driven by a data-collecting, AI-directed, technological doppelgänger nightmare. AI can only ever spit out what you feed it in the first place; that’s what makes it so completely counter to genuine creative diversity. Feed a virtual reality scenario the hubris of mankind and eventually, you’ll get to watch it fall with your own eyes in record time.

What makes Loop work best is that, despite all appearances to the contrary for most of the novel, it is so intricately linked with its two predecessors that we are able to see the seeds of Sadako at work long before her official introduction. Even when she is nowhere at all, she is effectively everywhere at once. She’s the face of the virus consuming the lives of millions in the real world, and the mother giving (re)birth to Kaoru/Ryuji in the virtual.

Also Read: 8 Horror Novels That Need a Film Adaptation ASAP

Suzuki’s third entry in his twisted trilogy loops so far and so well back on itself that it consumes everything about its predecessors and recontextualizes them completely. Sadako begins as the villain thanks to her considerable body count, but by the end of Ring we know the truth—her rage is based on a need for her suffering to be known. That it manifests how she experienced it is merely the only way she has learned that anyone will listen.

By the end of Loop, however, it is somehow so much worse. Because as it turns out, her suffering was at the hands of man and man-who-played-god. Her rage is so great that it found its own way out to infect both worlds. She will not be silenced and she will not be controlled. She will be heard if she has to take the whole of creation down with her until hers is the only voice and visage left.

Categorized:Editorials