How ‘Resident Evil 2’ Helped Me Heal

I’ve spent my life moving through different phases of horror, usually reflecting and acting as an outlet for something I was experiencing in my real life. I had a childhood obsession with Stephen King’s Pet Sematary when I first learned that pets and family members will someday day. The xenomorphs of the Aliens franchise (and Giger’s artwork overall) resonated with my horrifically dysphoric and suicidal ideating puberty. When I began trauma therapy in my 30s I hyper-fixated on rape-revenge movies (shout out to Alexandra Heller-Nicolas, your book was used more than once during therapy).

The single constant horror media that has been omni–present is survival horror games. Rather than make me passively observe an expression of my fears, they put me directly into the terror itself. Survival horror games allow me the catharsis of fighting back in a way I am not physically able to in real life. The one foundational work that ignited a fire on a fateful night in 1998 and continues to assist in my processing and (shockingly) healing is one of the most iconic games ever made: Resident Evil 2.

Also Read: The Arthouse Origins of Wes Craven’s ‘The Last House On The Left’

Some of my personal lore (a fancy way of saying I’m gonna trauma dump): I’m a survivor of a sexually and emotionally abusive childhood. This has also formed the backbone of my relationship patterns, and I’m embarrassed to say it’s led me to continually play out a cycle of retraumatizing myself by gravitating to toxic partners who would harm me in similar ways.

I have been formally diagnosed with cPTSD, a complex form of post-traumatic stress disorder that is a result of long-term abuse versus single instances of trauma. My body has been in hyper-vigilant mode for almost all of my 36 years; a sudden loud noise or something appearing in the corner of my eye can be enough to completely destabilize me, and in terms of media just the reference or implication of sexual assault has led to meltdowns (the website unconsentingmedia.org has been a lifesaver if I’m checking out a new movie).

While this can make a fair amount of horror difficult for me to get through, much less approach, it is the one genre of art from which I’ve ultimately found the most catharsis. Researchers have actually done studies on horror fans and discovered that there are chemical reasons for enjoying horror, as well as psychologically healing reasons. For someone like me, horror is almost like exposure therapy; I might get triggered, I might get hurt, I might have worse nightmares, and I might even spiral into a full-blown episode complete with dissociation, sobbing. And yet I also overcome some of my nervous system activations. Games do this on a level I can’t even begin to articulate.

Also Read: It’s All Disco: Bobby-Lynne, Pearl, and Queer Representation in ‘X’

It’s a core memory of mine in 1998, when at 11 years old my parents very sternly forbade my viewing or playing of Resident Evil 2 after I nearly drooled over those insanely questionable commercials on broadcast TV. But, classically, this just made me want it more, and I slipped my way into playing during a sleepover at a friend’s house. There is something so significant about those early Resident Evil games: the jarringly fixed camera angles, the pervasive dread of being low on ammo and health, the easily overwhelming enemies. They practically took the ‘fight or flight’ response and put it in 32 bits.

I was beyond hooked—I was obsessed. I didn’t have the ability to articulate it at that age, but my body was reacting to my experiences at home. Basically, the mechanics of the gameplay in Resident Evil resonate with my triggers. I am quickly activated by loud approaching footsteps or pounding on a door or wall, and a persistent nightmare of mine is someone breaking into my room while I’m in bed and I’m frozen.

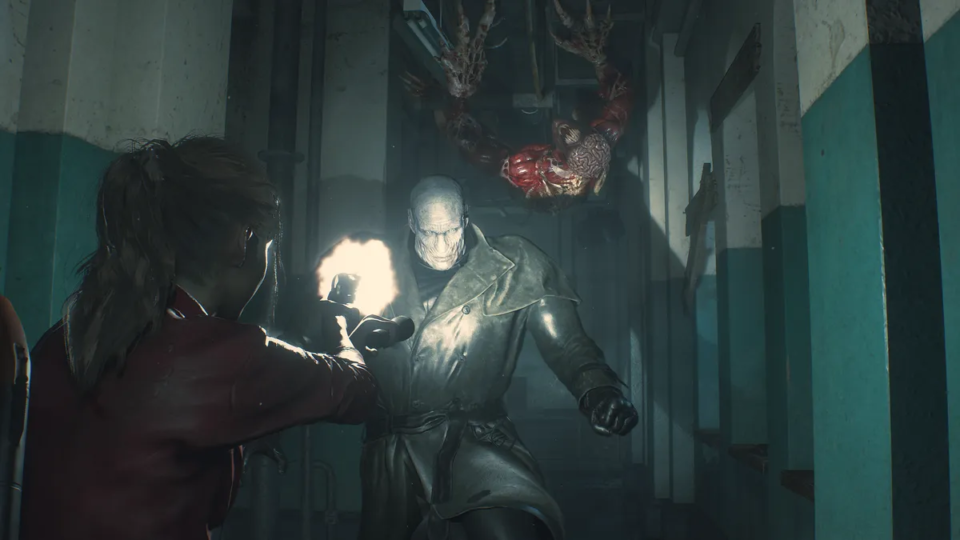

Resident Evil 2’s Mr. X is a pervasive tormentor who can appear at random times, often being announced by loud approaching footsteps or loud crashes. At home, I was living in constant anxiety from living with my abuser; terror was my resting state. The fear I feel playing under the constant threat of an unkillable monster jump scaring you with or without warning, and all you can do is really just run or endure the attack; it’s as if I was (and am) playing out the exact thing I was tortured by, albeit exaggerated by genre.

Also Read: 5 Terrifying Immersive Sims to Play After ‘Amnesia: The Bunker’

Playing Resident Evil 2, and the whole reason I hold survival horror games in general as my absolute favorite, renders these constant blights in my mental stability as conquerable; I can run, I can overcome, and eventually, I get the right weapon to blow it to bits. And now I have the benefit of some years of therapy and healing work—sort of like taking your favorite meal and dousing it in the perfect hot sauce.

This year, I’ve finally been able to play the remake of Resident Evil 2, and I hate to sound so dramatic over a somewhat campy zombie video game, but it feels a little life-changing. I’m not much of a gamer in the way most would classify, but I am continually astonished by how much has been improved—graphically, of course, but the newer mechanics give even more control to my diet vengeance. The stomping of Mr. X growing so close my heart rate leaps, that punishing sound design, the distance of fixed angles now replaced by uncomfortably close over-the-shoulder, no time to relax like I could in those long door-opening load times.

Also Read: The Liminal, Queer Horror of Kitty Horrorshow

In a sense, I’m micro-dosing trauma, much in the way I would when I choose to watch a rape-revenge movie. I’m intentionally triggering myself, or plucking my nerves in order to not only recognize it and really feel it in my body, but to also reclaim control of it. I can’t help but fist pump when Claire Redfield shouts “suck on this, fucker!” before unleashing the game-finishing killing blow with an impossibly giant gun. To paraphrase Kristin Hayter (Lingua Ignota), self-care can’t always be gentle.

Speaking of Claire, while I love baby girl Leon with all my heart (the only men I form crushes on are animated), her plot line adds even more depth to my processing. That has everything to do with the characters of Sherry and Annette Birkin, and how the whole experience feels like a realization of IFS, the type of therapy with which I’ve had the most success.

Also Read: Revisiting the Transgressive Feminine Power of ‘Wicked City’

IFS (internal family systems) aims to reprocess traumatic events by analyzing multitudes of “you” (your rage, your fear, your inner child) and turning them into ‘parts’ that can be integrated—which is a more complex way of saying ‘make friends with your demons’. When you are triggered, dealing with a flashback, or re-experiencing the remembered emotional and physical state you were in during the actual event of your trauma, IFS teaches you to visualize the terror itself, to acknowledge it as a survival tool, as something not antagonistic but truly there to help (however chaotic that help may seem). At least with my therapist’s help, I turned different aspects of my episodes (my horror, my rage, my resentment) into something I would almost welcome, giving it the acknowledgment it seeks before letting it go and pass through me.

Anyways, how this relates to Claire’s storyline is how I find myself projecting my IFS work onto the characters; if I am the role of Claire, then Sherry is the little girl I was who desperately needed saving, and now as an adult, I can actually save her. Annette takes the form of the cold and emotionally abusive parent who should have been my guardian but instead objectified me. And Chief of Police Irons, during the section where you assume the role of Sherry, is every man I have ever known in all my years, and dear reader you know exactly what I mean by that.

Also Read: Vanessa Valdeon, ‘Urban Legends: The Final Cut’, And Queer Characters In The Early Aughts [The Lone Queer]

Ironically, it’s this sequence with a regular human man chasing you as you play a defenseless little girl trying to hide—not the zombies, not the monsters—that takes the cake for being the most terrifying piece of gameplay I’ve had put myself through. It’s little me, all over again, only now, I’m bazooka-ing the presence that is hounding me and additionally threatening to harm who I once was and still keep in my heart. It’s like a badass form of reparenting: “Don’t worry, sweetie, I’m your mom now and I’ve got the big guns.”

In the rise of cozy game culture, I play Resident Evil 2 to be soothed just as much as something like Stardew Valley. TV shows or movies will take me through the emotions of the situation but not truly allow any kind of proper closure or just leave me activated alongside the characters without tangibly giving me their resolution. In the landmark zombie game, I have control in fighting against that which haunts me. Suddenly, I’m not as scared of the dark. Suddenly, I’m okay when I have to sleep alone in the house. My friend recently called it ‘game-ifying trauma,’ and that feels brilliant.

Categorized:Editorials