In ‘Stories Untold’, The Medium Is The Monster

One of the first things you hear when you begin playing No Code’s 2017 horror anthology game Stories Untold, is a high-pitched, heavily processed digital scream. There’s a harmless explanation for the sound: It’s just the sound of your antiquated computer booting up as you try to load a text-based adventure game. It’s the kind of thing that entertained countless gamers of yesteryear. The boot-up sounds are discordant, but ultimately mundane. At first, anyway.

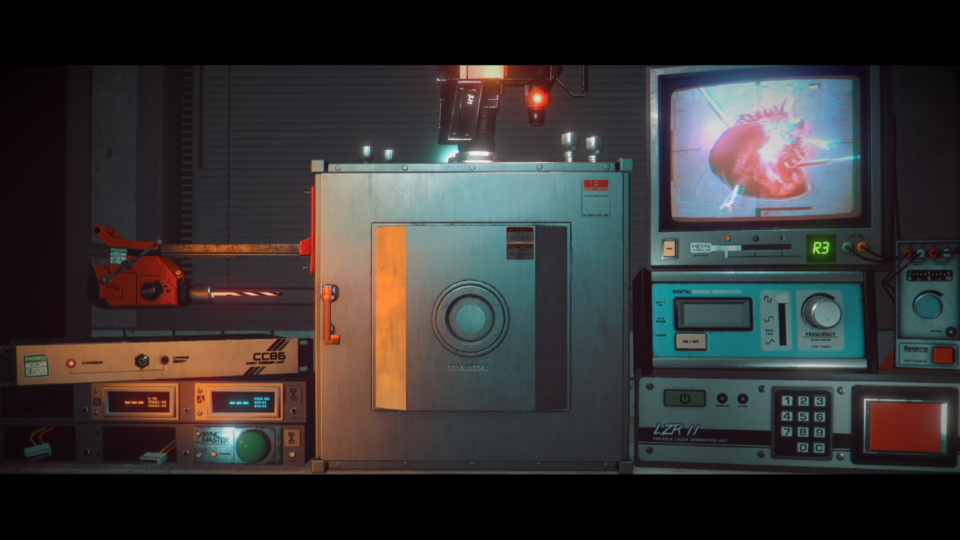

Stories Untold is full of these little moments, where a quirk of a machine rides the line between normal and nefarious. As a whole package, Stories Untold passes itself off as four seemingly disparate horror game micro-experiences. The first, the aforementioned “The House Abandon,” involves playing a seemingly haunted (or at least troubled) old video game on a dark and stormy night. The second scenario, “The Lab Conduct” tasks players with conducting vague experiments on some unseen mysterious object—tests that begin very abstract and mechanical, but take an abrupt left turn into something more like an invasive surgery.

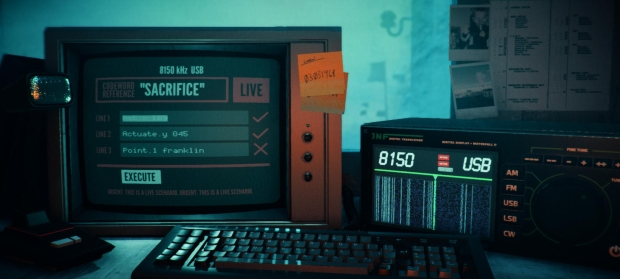

The third chapter, “The Station Process,” drops players at an Arctic research site, and tasks them with decoding cryptic numbers station broadcasts while something terrible is unfolding back in civilization. The fourth and final scenario connects the dots between the previous three but doesn’t introduce much new to the experience.

Also Read: ‘Stasis: Bone Totem’ Is A Breath Of Fresh Air For Point-And-Click Horror

In each of these scenarios, technology is used as a mediating factor. You, the player, the person who bought and started the video game, are controlling an in-game person who is doing the same things you’re doing in the real world—pushing buttons, typing commands, struggling to read the tiny font on a screen within a screen. The basic verbs of the game are related to your input into the device, not the character’s input. By adding this layer of mediation between player and action, Stories Untold makes every move you make in the game double within the game’s strata of reality.

The medium of the video game itself becomes a vector for horror, as the way you interface with technology both simulated (the in-game computer/monitor/radio) and real (the physical game you yourself are playing) contributes to the sense of mounting horror. The medium of the video game is itself being haunted.

Stories Untold belongs to a school of horror often called ‘Analog Horror,’ which derives its horror from seemingly mundane technology, and popularized by YouTube series like Local 58 and No Through Road. Stories Untold, like these series, mines tension out of the seemingly innocuous and banal, only to eventually bring paranormal horror crashing down. In each of Stories Untold’s scenarios, the machines themselves tell the story. The static on the screen, the feedback from outdated monitors, and the eerie misbehavior of these instruments that are meant to seem so familiar that they’re quaint, all contribute to the eerie sense of unease.

Also Read: A Beginner’s Guide To YouTube Horror [Video]

Machines malfunction, sure, but when does a malfunction become malicious? By playing a video game, players expect their inputs to be reflected on the screen. But when the screen displays a second, more fallible screen, the boundaries between input and execution can widen.

Stories Untold accomplishes much of this mounting discomfort by keeping the screen relatively sparse. That’s not to say the game is boring to look at. On the contrary, each space is lovingly rendered, with details like the wood paneling on a TV screen, small cosmetic chips in metal instruments, and visible distortions on microfiche reels all contributing to the tactile, tangible nature of these virtual nightmares.

But most of the tension comes from the information conveyed by these machines—beeps and hisses in the sound design or minor fluctuations in on-screen monitors that portend terrible happenings. For the most part, your view in each scenario is static. Your computer/monitor/workstation doesn’t change much, but what you get from it as each mystery unravels does. When, finally, the scene does change, and your space is invaded or disrupted, the invasion hits even harder, breaking what we had come to believe was an immutable rule of the space.

Each of the first three scenarios of Stories Untold takes a slightly different approach to these common themes of malevolence within machines. In “The House Abandon,” you play the titular game on an in-game wood panel TV, a slice of vintage simulation to better sell the nostalgia-bait premise. In this game within the game, as you type your way through text-based adventure game puzzles, you eventually stumble onto…a wood-panel TV, with which you can play a game called “The House Abandon.”

Also Read: How ‘Resident Evil 2’ Helped Me Heal

This mirror-reflecting-mirror scenario quickly tumbles into its logical conclusion, as elements in the game-within-the-game-within-the-game ripple upward and outward. Digital warnings about a clap of thunder literally echo in your ears, and changing elements of the room within the game likewise ripple out into the room you’re sitting in. The jumbled layers of mediation and reality are confusing, yes, but undeniably effective. In a text-based adventure, you only know of your surroundings what the text tells you, leaving an awful lot of things “unseen” until the text reveals things to you at opportune moments.

The effect here ultimately makes you feel like the game is intentionally hiding information from you—toying with you, withholding what you need to know until it’s too late. The retro game first appears like a nostalgic trip down memory lane, only for those memories to become weapons. Hiding from the truth of the past is a key narrative element in “The House Abandon”, and its climax involves violently ripping away false idealizations of the past. The past was always this scary. Pretending it wasn’t won’t make it true.

The second chapter, “The Lab Conduct”, begins by upping the number of monitors available to the player by a hefty amount, as you now must engage with multiple instruments to conduct ambiguous lab tests on an unknown sample of some sort. These tests include microwaves, X-rays, radio frequencies, and a drill. The tests start harmlessly enough, but that drill is just sitting there the whole time, promising an eventual escalation, and once the escalations start, they do not let up. Some tests return inconclusive findings, offering no details of your tests’ purpose, and others reveal organic material. Flesh sizzles and pops when exposed to microwaves. The instruments fizzle out and seem resistant to your wishes.

Also Read: The Liminal, Queer Horror of Kitty Horrorshow

The machines here, just as in “The House Abandon”, are mediating tools—things that both distance you and connect you from the true horror lurking within the container. The machines dictate how you learn about what’s going on. Because they determine what you know, they also determine what you don’t.

There is horror in the gaps between what we know, and the third chapter of Stories Untold, “The Station Process”, highlights this fact perhaps most explicitly. At your arctic research base, you and several other researchers (with whom you can only communicate via radio) juggle between cryptic sequences on a Numbers Station and an esoteric handbook on microfiche, struggling to parse out answers and codes on a small screen-within-the-screen. The sense of claustrophobia is inescapable in this chapter and arctic winds howl throughout, rivaled only by the endless hiss of the radio.

The numbers from the number station, and the codes they correspond to, make little sense to you, the player, or the character you control. Your fellow researchers don’t know much more than you do. Between the technology and the information it’s meant to convey, nothing is actually known by those communicating it all. Again and again, you must decipher an impenetrable code, and the answers you receive for doing so make less sense than the question.

Also Read: The Changing Face of Death in the ‘Amnesia’ Series

Everywhere in Stories Untold, machines are used to attempt to discover something, but the answers are incomplete at best, and either inscrutable or damning at worst. These machines, with their radio waves and data streams and curious readings, convey information, but it’s not the kind of information we can understand, or act on in any way that prevents the frightening climax of each story. Even when we receive warnings, we’re either unable to heed them or unable to comprehend that they’re warnings at all. The technology at hand cannot convey the full nature of what we need to know.

Media philosopher Marshall McLuhan once said that “the media is the message.” He expounded on this phrase by saying, “…This is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium—that is, of any extension of ourselves—result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.”

In the context of Stories Untold those “social consequences” that arise from the medium of video games are actually intertwined not just in the new scales of technology, but in the compounding effect of old technology as it is outpaced by the future. As new technology and new culture give way to new senses of the self, and the past gets increasingly siloed into different eras, throwback genres, and flavors of nostalgia, a curious sort of transformation takes place. These past forms, once so familiar and ubiquitous, become uncanny and unfamiliar. The digital screams of a dial-up connection, or the static between radio stations, once everyday occurrences, become out of place and foreboding in their alienness.

Also Read: Digital Ghosts and Stunning Architecture in ‘The Haunting’

Let’s return to McLuhan, who said, “Everybody experiences far more than he understands. Yet it is experience, rather than understanding, that influences behavior.” Much of how we interact with the world is indeed predicated on what we’ve done before, what we have experienced, as opposed to just what we’ve been told. You can read a driving manual all you want, but if you want your license, you’ll still need to prove you’ve parallel parked at least once.

But the inverse is also true—we act in ways based solely upon our experiences, but no real knowledge. I don’t know how a phone works, not really. I know how to make calls, take screenshots, and change my voicemail. But I can’t comprehend the code that lets me do these things, or repair my phone’s battery. I act with experience, but not understanding. As so many people do with older machines like the radios and monitors of Stories Untold. But what we don’t know might be able to hurt us. If there’s something lurking within the wires—between the channels, among all of that static—how would we even know?

Categorized: Editorials