Wes Craven And The Art of the Chase

Wes Craven was and will remain the greatest humanist horror filmmaker of our time. It’s an argument I’ve made countless times before, though it bears repeating. Craven fundamentally understood the ethos of the narrative paradigm, our capacity to instill and draw meaning from the stories we tell and consume. While Craven told many stories, pulling back the curtains on the “insane asylum” in his own words, his guiding prerogative was to reinforce the value of life. Living matters. The people we love and care about matter. Horror is both a threat to that and a reminder of what ultimately counts the most. In his own words,

“In real life, human beings are packaged in the flimsiest of packages, threatened by real and sometimes horrifying dangers, events like Columbine. But the narrative form puts these fears into a manageable series of events. It gives us a way of thinking rationally about our fears.”

As a framework for some of the horror genre’s greatest hits, Craven was remarkably equipped to cultivate the right kind of fear. With horror, if characters don’t matter, their subsequent deaths don’t either. While a trademark of tawdry, low-budget slashers from the 1970s onwards (including some of my favorites), gratuitous tapestries of death can never hope to achieve the kind of longstanding efficacy and meaning as horror with intent. That intent doesn’t need to always be meaningful characters—horror can spill blood with abandon and still make a stirring point. However, for Craven, the innate humanity of his victims was always at the forefront.

It is, at its core, what distinguishes Craven’s kill scenes within the realm of death and bad deaths. Conceptually, the idea posits that while characters die in every genre of film known to man, horror is uniquely poised to achieve the bad death. This death is unique insofar as its conditions and consequences extend beyond the loss of life. Think of damnation or possession, or in the Alien franchise, having one’s body rendered host for a horrific extraterrestrial lifeform. Bad deaths can just as easily be a simple stabbing or gunshot, though the consequences must burrow deeper in the marrow, and hurt the audience more than a throwaway, off-screen kill might. In his chase scenes, Craven mastered the art of the bad death.

Coupled with his inimitable understanding of character and humanity, Craven’s chase scenes—of which there are several across his storied film history—adroitly render his characters more than fiction, more than boldface font on a script. They are, in turn, both audience and creator, friend and family. They are persons known intimately to strangers, conceptions whose deaths hurt because their fictional lives mattered. The chase scene, a horror staple that often ends in death, was Craven’s way to instill fear and remind the audience that the person being pursued matters to them.

What Makes A Good Chase Scene

To start, the chase scene should be defined. Much like how the jump scare, another horror mainstay, is defined as an abrupt shift in either sound or image whose intent is to rouse the audience from their seat (in other words, the musical sting when something startling appears), the chase scene can be easily synopsized. In my own words, the slasher chase scene is best described as a sequence where a character is pursued by the villain through a clear, defined locale. Setting is key to the chase scene. Without clear parameters of space, the chase feels nebulous. Consider Sarah Michelle Gellar’s infamous I Know What You Did Last Summer chase, a clear homage to Wendy’s (Anne-Marie Martin’s) protracted pursuit in Prom Night, compared to Halloween Kills’ chase of Lindsay Wallace (Kyle Richards).

The former chases are tense and exciting. The latter is ill-defined. Michael and Lindsay proximally occupy the same space in the park, though distance and threat are equivocal. Where one is compared to the other—what their line of sight might be—is hazy at best.

Wes Craven’s chases are different. Taking the best of what came before and scaffolding the framework for what would come later, Craven’s chase scenes are not only propulsive but proximally coherent. They serve a purpose beyond tension, often augmenting key character traits or delineating the full scope of a movie’s threat, whether supernaturally or human. They were and remain the best part of his filmography. As an ode to Craven’s remarkable achievements, this piece will highlight some of the best he’s done, not just from my perspective, but from other horror fans and critics alike to celebrate the man, the legend, and—of course—the chase.

A Nightmare on Elm Street

Six years before Home Alone, Nancy Thompson (Heather Langenkamp) put Kevin McCallister to shame. A hypnagogic, nightmarish classic, Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street was a violent odyssey with bootstrap, Rube Goldberg trappings. Wickedly inventive and unconventionally brutal, it was the slasher villain made supernatural. Still, even ghosts can be hurt.

An early chase that sees Nancy fleeing from Freddy Kreuger (Robert Englund) as he kills Rod in his jail cell is an early high point, a beat that punctuates one of the genre’s greatest jump scares. Nancy, believing she’s safe at home, is attacked as Freddy jumps through her bedroom mirror, tackling her before they wrestle on the bed. Replete with indelible horror imagery—Freddy breaking through the front door, the stairs turning to mush as Nancy climbs—Craven’s visceral sense of urgency here renders it a chase for the ages. Tina’s (Amanda Wyss) introductory chase is no less effective. Craven, who scripted the movie as well, uses supernatural bearings to keep the audience on edge, delicately blurring the line between reality and dreamscape. His carnage, however, is never anything less than real.

In the finale, Nancy successfully pulls Freddy into her world, assuming that it’s the only way to stop him (with seven sequels and a remake, that didn’t seem to be the case). Glen (Johnny Depp) has just been eviscerated in his mattress, his guts splayed on the ceiling of his rotating bedroom, and Nancy has had enough. She booby-traps her home to slow Freddy’s pursuit. A sledgehammer smacks him in the chest, lamps are trip-wired with explosives, and in the basement, Nancy successfully sets Freddy ablaze. It isn’t enough to stop him—there are, as noted, several sequels—though as a capstone to one of the greatest slasher movies ever made, few could ask for more.

This chase was the final girl as warrior. The final victim declares they won’t go down without a fight. Antecedent horror protagonists did plenty of running, though they only fought when there was no choice left. Nancy, as scripted by Craven and brought to life by Langenkamp, was and remains a different beast altogether.

Scream

Acclaimed horror author Max Booth III argues that Casey Becker’s opening chase in Scream is Craven’s best—and you can trust his knowledge of claustrophobic terror as the writer of We Need to Do Something. Max says,

“[My] favorite chase scene is definitely the opening of the OG Scream. Also maybe the slowest chase scene I’ve ever seen outside of the OJ Simpson tape. Drew Barrymore stumbling through the grass, reaching for her parents, seconds away from getting a slit throat. Hard to beat that.”

When choosing a chase scene to spotlight here, Casey Becker’s was also my first instinct. While I’ve controversially argued that Scream 2 might have the better opening, there’s no denying that Becker’s inceptive franchise death, as played by Drew Barrymore, yields considerably more cultural relevancy. Even horror detractors know of the scene’s monumental legacy. Craven’s simple front lights, his penchant for remarkable establishing shots and sense of space, and the slow descent into gruesome terror as Becker realizes her friendly caller isn’t so friendly remain not just franchise high points, but genre ones, moments in horror that match the efficacy of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho shower scene.

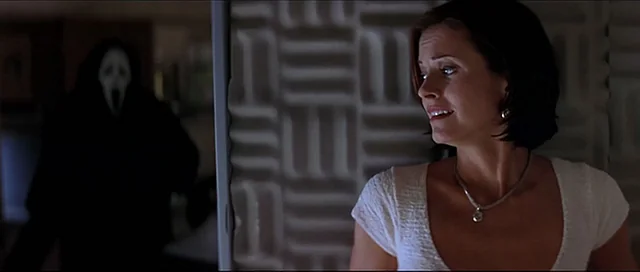

Yet, despite the impact, I ultimately opted to go for Sidney Prescott’s (Neve Campbell) third-act chase at the Macher house. Sidney Prescott remains a perennial rule-breaker. While Randy Meeks’ (Jamie Kennedy) horror rule monologue hasn’t aged so gracefully (presuming it was even accurate at the time), there’s no denying the lack of sexually active, mainstream horror final girls. Prescott’s bucking of convention is best conceptualized after she sleeps with to-be killer Billy Loomis (Skeet Ulrich) while a party rages on downstairs. She brushes her hair and not-so-subtly interrogates Billy about an earlier attack, still suspecting him to be a killer. Ostensibly, her worries are buried as Ghostface emerges from behind, slaughtering Billy and giving chase.

Sidney races from bedroom to hallway, throwing everything at her disposal at Ghostface to slow him down. She ends up in the attic, frantically calling for help. It’s to no avail, and soon, she has no choice but to open a window and crawl onto the roof. Sidney is quick, but Ghostface is quicker. He appears, they struggle, and her grip is lost. She plummets off, saved by a conveniently placed boat before racing off into the fields.

Sidney’s chase, and Craven’s direction, exemplify what makes a good chase scene, well, a good chase scene. Its origins as a post-coital bloodbath are as unconventional as they are progressive. Sidney, despite once before having noted the density of horror protagonists running vertically when they should be heading toward the door, is corralled into the Macher home’s upper levels. Sliding doors, connecting bedrooms, and narrow hallways illustrate Craven’s firm control of the environment. His chases make sense because the architecture makes sense. And, perhaps most fundamentally, it’s a remarkable subversion of slasher tropes.

The slashers of the 1980s regularly concluded with extended chases. Think Alice’s (Adrienne King) race through Camp Crystal Lake in Friday the 13th or Ginny’s (Amy Steel) even better sprint in Part 2. Conventionally, the killer reveals both themselves and the present threat. The so-called final girl repeatedly encounters and dodges the killer, moving like game pieces from one set piece to another; broken down car, kitchen pantry, under the bed. All the while, the final girl stumbles across the corpses of peers slaughtered in secret earlier. While the audience knows of their deaths, the character doesn’t.

Here, before the third act even starts in earnest, Sidney encounters the body of best friend Tatum (Rose McGowan) as she dangles like garland from the world’s strongest garage door. It’s a reversal of horror fate, and better still, Sidney gets another equally exhilarating chase several scenes later. There, she escapes from a news van and police cruiser before returning to the house for all the blood-soaked reveals.

Scream could easily have devolved into parody. But with Craven behind the camera, the humanistic stakes are central, forces of gravity around which the meta-commentary ably revolves. Its chases are thrilling, adrenaline-junkie stuff, as stylish as they are visceral and well-crafted.

Scream 2

I’ve argued before that Courteney Cox’s Gale Weathers is the Scream series’ secret weapon. Well, not so secret seeing as she’s the only cast member (Roger Jackson aside) to appear in every entry. Weathers is the ideal embodiment of Craven’s horror sensibilities. Though conceived by writer Kevin Williamson, Craven and Cox gave life to Gale Weathers’ ferocious scoop chaser. In any other horror franchise, Weathers would have met her end in the first entry. Six movies in, she’s still holding her own (her Ghostface call in Scream VI is undoubtedly a franchise high point).

Weathers’ best moment is widely considered to be her Ghostface chase in Scream 2. In fact, it’s arguably the series’ scariest moment, second only to the first’s infamous opening. For decades, fans have been clamoring for more moments just like that. Just a killer, a scared victim, and a boundless space through which they can run.

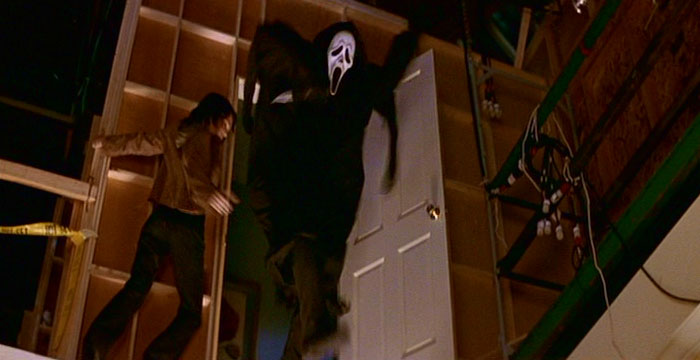

Weathers and David Arquette’s Dewey are reviewing crowd footage of Gale’s from Windsor College, wisely presuming that if the new killer (or killers) are really relishing this new slate of killings, they’d likely be somewhere on those tapes. Ghostface, as he is wont to do, intercepts the two. Popping up in a fantastic scare, he lunges at Gale as Dewey (in conventional Scream buffoonery) stumbles down the auditorium stairs, desperate to reach her. Gale, despite not having had a direct encounter with costumed Ghostface before, is equipped to handle herself. Craven’s trademark tactility is again spotlighted, with Gale diving over desks, Ghostface’s knife clinking against resin, and a meta phone to the face as Weathers grabs one off the hook and nails him with it.

Dewey is off-screen recovering as Gale races down the film department hallway. She tries every door she can, though most are locked. Marco Beltrami’s score is chef’s kiss as Weathers desperately tries to flee. She soon finds an open door, hiding away in a sound booth. It’s classic suspense as Ghostface appears, not spotting Gale in the other room. The two silently dodge one another in a breathlessly tense dance until Gale successfully slips away. Dewey finds her then, across the glass, though the room is soundproof. It isn’t until he can turn on the microphone that Gale spots him, just as Ghostface appears to stab him in the back.

It’s a heartbreaking scene, and like the first, it all but confirmed Dewey’s death. Of course, he doesn’t die here, and credit must be given to Craven and Williamson for their subversive commitment to the core trio. Few, if any, horror franchises have had as much love and dedication to their core cast as Scream has. Sidney, Dewey, and Gale were more than throwaway victims—they were mainstays. Craven wouldn’t do away with them that easily. In fact, Craven himself didn’t do away with them at all.

Franchise fan Eric of Dark Projector had this to say:

“The film department chase sequence in Scream 2 is the best chase sequence that Wes Craven shot as a filmmaker. This dramatic moment shared between Gale and Dewey as they are running from Ghostface gives Craven the opportunity to showcase his mastery of the cinematic frame. He perfectly utilizes foreground, midground, and background to place Gale in harm’s way while also alerting the viewer where Ghostface is currently stalking. It’s beyond effective and is the perfect showcase for Craven’s talent as a filmmaker and his ability to thrill and excite audiences.”

Fan Christian McKnight similarly highlighted Scream 2, though Cici Cooper’s (Sarah Michelle Gellar) chase resonated the strongest with him. He said,

“An opening kill in a slasher is important and should be iconic. Nobody does this better than Wes Craven. Scream had the famous Drew Barrymore scene and Scream 2 had a chase with Sarah Michelle Gellar’s Cici Cooper. SMG is phenomenal (huge fan btw) and the 90s had a love for killing her off. Cici’s death set the tone for Scream 2. It was new and fresh. It was different than before. This chase scene encapsulates this perfectly. Cici is violently stabbed, but that’s not the cause of death. She is thrown from the top of her sorority house, left broken and bleeding on the pavement below.

The thing that makes this scene so special is not just a run through some random empty house. It’s a real house, full of decor and objects owned by girls out partying. And all of this comes into play. Craven uses every single piece of the set in the Cici chase. She trips over the table the phone is resting on when Ghostface bursts through the door. She is using the stairs and handrails alongside them to try and help quicken her escape. A potted plant at a turn in the stairs is a weapon she uses to defend herself. A bicycle that presumably belongs to one of the girls is used to slow Ghostface further. All culminating in a scene where Cici is tossed through the double glass doors that lead to a balcony on the top floor, where she is thrown to her death.

The mastery that Craven wields over the chase scene is so evident here. He uses the set as if it is actually alive, and not just a set. And he sets the tone for a brutal and exciting sequel with a scene that (almost) rivals the historic Drew Barrymore opening.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Scream 3

While some fans argue Scream 3 was and remains the weakest entry in the franchise (I’m sorry, that’s wrong, it’s Scream 4), it holds up considerably better in retrospect. It’s a fitting end for Sidney Prescott and had the franchise continued without her, I wouldn’t have minded all that much. Thematically, the past isn’t dead in Scream 3, and it’s a throughline Craven uses to stage one of the series’ best setpieces.

Though sidelined for the first half of the movie on account of other commitments, Prescott takes back the final girl mantle in a full-throttle finale. Arriving in Hollywood to connect with the rest of the cast, Prescott is led to the Sunrise Studios backlot to investigate the origin of her mother’s photographs that have been appearing at different murder scenes. While there, she is somewhat incredulously led to a shuttered set for movie-within-a-movie Stab 3. It’s Woodsboro.

Soundtrack staple “Sidney’s Lament” fades in as Sidney wanders through uncanny (and tragic) recreations of the first movie’s many deaths. There’s the bloody garage door where best friend Tatum died, her bedroom is a hot set (and she even hears Billy Loomis in her head), and as she backs up to the window, Ghostface pops up to pull her through. Resultantly, she runs the gamut of the series in memoriam, replicating several early chases, including her infamous jaunt up the stairs (when she should have been going out the front door).

Franchise fan Caleb Ward has this to say:

“Sidney being chased through the model of her old house is not only an intense moment narratively but an emotionally resonant one as well. Ghostface forces her to relive and revisit the events from the first film, the memories that she had purposefully been trying to move away from, in such a literal way. Paired with the visions of her mother, this chase’s meta qualities provide an incredible experience and really drive home one the main themes of the movie (and the entire series)—Sydney can’t seem to escape the past.”

It’s a brief scene, though as a love letter to the franchise and Sidney’s own growth, it’s remarkable. While she’s frightened to death, she holds her own, fending off Ghostface long enough for help to arrive. You can’t move forward without reconciling with the past, and in Scream 3, that’s exactly what Craven and company do.

Cursed

It’s fair to blame Cursed for the derailment of Craven’s career in Hollywood. Derailment isn’t quite the right word, but while Cursed and Red Eye were released in the same year, it would be another five years before Craven was behind the camera again. That, unfortunately, would be My Soul to Take. A year later, he helmed Scream 4, though afterward, he didn’t direct again before his untimely death in 2015. Neither of his final two movies is indicative of his best work. They have their fans, though there are few standout moments in either. Craven himself has remarked how exhausting the Scream sequels were to him. After the inordinate studio interference on Cursed, it’s easy to see why the magic of moviemaking dissipated quicker than Judy Greer in a Hollywood club.

Listen, Cursed is contemporary camp, but there’s no denying it’s a movie at odds with itself. It wants to be Scream, though it’s incredulously PG-13 (even the much-touted unrated cut does little to remedy this). Extensive reshoots and cast changes (at one point, Skeet Ulrich was starring) resulted in a hobgoblin of a horror movie, a horror picture all but visibly coming apart at the seams. Stars Christina Ricci and Jesse Eisenberg have both spoken at length about how discordant the production was, and it’s fair to say Weinstein interference has buried the possibility of ever catching a glimpse of Craven and Williamson’s original vision.

Well, there is one glimpse, and it comes in the form of some gnarly makeup effects detailing the aftermath of co-star Mýa’s death in a Fangoria spread. Not even the unrated cut features the scene, a casualty of studio interference and executives with whims as arbitrary as a child. Craven, speaking with The New York Post, said,

“I’m very disappointed with “Cursed.” The contract called for us to make an R-rated film. We did. It was a very difficult process. Then it was basically taken away from us and cut to PG-13 and ruined. It was two years of very difficult work and almost 100 days of shooting of various versions. Then at the very end, it was chopped up and the studio thought they could make more with a PG-13 movie, and trashed it. We were writing while we were shooting. It wasn’t ready to film. We rewrote, recast, and had two major reshoots. It went on and on and on.”

While Craven may not have recognized it himself, Mýa’s chase scene and subsequent death is an outlier in Cursed, a scene that is imbued with the best of Craven’s filmmaking prowess, even in the butchered final cut. Mýa’s Jenny is leaving a party and is attacked in a parking garage. Cars are crushed, tension is stretched to a sensational breaking point, and ultimately, she is mauled (off-screen) in an elevator.

Erica Russel had this to say about the scene:

“Even though his 2005 creature feature Cursed is remembered as a bit of a maligned mess among horror fans (Craven himself disliked how the film turned out after the studio sunk their claws into it post-production), the parking garage scene featuring a leopard dress and cat ears-clad Mýa getting stalked by a hulking, pissed-off werewolf remains a standout. Featuring shifting POVs between predator and prey, it’s a genuinely tense moment in an otherwise silly, campy film that brilliantly culminates with an (implied) elevator bloodbath. (PS: Add this one to the great pantheon of stressed-out pop stars running for their lives in horror movies, right alongside Brandy in 1998’s I Know What You Did Last Summer and Paris Hilton in 2005’s House of Wax).”

It’s a worthy addition to the pantheon, no doubt. Even if Craven himself couldn’t see it (and no one could blame him), Cursed has enough of his DNA in it to work. While it’s unfortunate he wasn’t around to see its quasi-reclamation (thanks, Shout Factory) on home video, it remains a frustrating, though no less noteworthy, footnote in the career of one of horror’s best.

Red Eye

Wes Craven’s Red Eye, scripted by Carl Ellsworth, is one of Craven’s most taut offerings. Unconventionally PG-13, Craven is mindful not to skimp on the terror. While the thrust of Red Eye is retrospectively incredulous, it’s a testament to how assured a filmmaker Craven is that during its irregularly brief runtime, logic doesn’t matter as much as classic, old-fashioned cinematic suspense.

While most of the film is set aboard the titular flight, with Rachel McAdams’ Lisa menaced by Cillian Murphy’s Jackson as he endeavors to coerce her into facilitating an assassination for the following morning, Craven’s penchant for visceral, tactile terror is given free rein in the third act. Tension reaches a boiling point when Lisa stabs Jackson in the throat with a pen, absconding quickly from the flight (much to the chagrin of other passengers) as he pursues her. Here, Craven pays off early signs. Pen as weapon and little girl as obstacle—introduced an act before—have their moment, slowing down Jackson’s frantic pursuit of Lisa.

They first race through the airport at a breakneck pace, though Lisa successfully steals a car from the departure gate. Plot threads coalesce, and Lisa must not only make it to her father’s home in time, but simultaneously reach the hotel she manages to save the target. Luckily, both Ellsworth and Craven quickly do away with the hotel threat. There’s a big explosion, but Lisa’s call comes just in time to get everyone out. The real meat of Red Eye’s final act is much more personal.

Craven’s chase scenes have always been uniquely physical, and in a small, domestic showdown, his slasher roots prove invaluable. Lisa rams her car into an unsuspecting assassin, though audiences know he’s not the real threat—Jackson, wherever he might be, is. Of course, he’s there, and audiences might be forgiven for thinking Red Eye was another Scream movie. Jackson blunders like Ghostface has for decades, repeatedly stopped or slowed down as Lisa makes use of domestic weaponry—vases, field hockey sticks—to stay alive.

As always, Craven’s mastery of cinematic space augments the terror. The house is under construction, and though this is the first audiences are really seeing it, the layout is immediately clear. Craven’s control here culminates in a terrific jump scare as Jackson appears behind a closed door, charging at Lisa with a knife. They struggle until Lisa is thrown over the banister onto the stairs below. While ultimately triumphant, audiences are left catching their breath.

Slasher stakes rarely feel this high, and while movie history tells us Lisa will be okay, the visceral physicality of the protracted chase through the house suggests otherwise. Small touches—Lisa smacking a knife away on the floor, a call to the police we suspect to be interrupted but isn’t—reinforce Craven’s total control. It’s a chase with both guts and hearts, ably demonstrating that no matter the story, Craven could make most anything work.

Certified Red Eye fan Raleigh Joyner had this to say:

“Since Wes Craven is primarily known for his work in horror, it may be easy to overlook that he also made a fine contribution to the thriller genre in 2005: the lean white-knuckle airplane flick Red Eye.

The third and final act of the film begins with clever Lisa Reisert (Rachel McAdams) stabbing Jackson Rippner (a menacing Cillian Murphy) in the throat with a pen, then high-tailing it off the plane and through the main terminal of Miami International Airport. Jackson pursues her with his crude new tracheotomy concealed by a lady’s silk scarf; sputtering as he does, with audiences getting an early glimpse into the magic of Murphy’s distinctive smolder, he is as terrifying as any monster in a slasher. Also pursuing Lisa are the police, as everybody else is clueless to Jackson’s sneaky villainy – except for a young girl who has been on to him since the beginning of the flight, and helps Lisa buy time by tripping Jackson in the plane’s aisle with her bag.

Lisa’s evasion of the police and Jackson alike proves a fascinating look into a world before ubiquitous and pristine quality airport surveillance. Were Red Eye made today, it would be impossible to believe somebody could lead the law on a chase through an airport without being identified and nabbed almost instantly. But, in 2005, this is still believable. Lisa manages to throw off both pursuers by hiding behind clipboards and magazines, while her frantic sprinting is likely dismissed by other travelers as just another unfortunate soul late for a flight. Resourceful and quick-thinking as she is, though, she still cannot escape the classic trope that befalls her horror heroine counterparts: she trips and falls.”

Beyond the core conceit being believable in 2005, I’d argue that it’s a movie Craven needed to make then, too. With Red Eye, he departed upon a career hiatus with a win. After the grief of Cursed, few deserved it more.

Conclusion

While not demonstrative of his entire career—both The Last House on the Left and The People Under the Stairs, for instance, have remarkable chases of their own, not to mention the much-maligned (but still fun) My Soul to Take—it’s a preview of the profound influence Wes Craven has had on the horror genre. Few filmmakers, genre or otherwise, have filmographies this extensive, this acclaimed, and this diverse. 4,000 words are enough to just barely scratch the surface, and even then, the masterful genre command is only marginally conceptualized. Craven’s work defies easy categorization or assessment—it has and still does deserve more. Craven as a filmmaker was always chasing the next great scare. Who knew that decades later, that chase would still be so thrilling?

Categorized: Editorials