A Night Alone In The ‘Ringu’ Cabin

Few horror movies this side of The Shining have managed to make a real-life lodging look as foreboding as the cabin in Ringu. Hideo Nakata’s seminal film, which brought J-horror scrabbling across the tatami mat to Western audiences at the turn of the millennium, isn’t necessarily the first place that would spring to mind when you think “horror holiday,” however. Ringu jumps around in location more than The Shining (inspired by the Stanley Hotel in Colorado, with exteriors filmed at the Timberline Lodge in Oregon). Yet the cabin at the nonexistent Izu Pacific Land in Japan is a location that becomes important as the film progresses. It’s also a cabin you can still find at a real place called America Camp Village in the mountains of Okutama, Tokyo.

Most genre fans, unless they’ve been living under a rock slab at the bottom of a well, should at least be passingly familiar with Ringu’s central plot device of a cursed video that kills anyone who watches it within seven days. By now, it’s become a well-worn franchise trope, littered across several sequels, one prequel, and an April-Fools’-joke-turned-Shudder-crossover with fellow J-horror breakout Ju-On (The Grudge).

The “ring” of the title started out as an ominous phone call — death on the line — and a virus before it became a visual like a solar eclipse in the American remake, The Ring. With its memorable tagline (“Before you die, you see the Ring”), that film found blockbuster success by grafting ideas from Ringu and its source material (Koji Suzuki’s novel Ring) onto a rainy Seattle backdrop.

Ringu and The Ring are both movies akin to Psycho in the sense that their most murderous twist is out there in the ether now, ready to be known through pop culture osmosis. Nevertheless, when the final call comes and the seaweed-haired ghost girl slinks out of the tele in her white nightgown, there’s no more horrifying image than the one in Ringu where we see Sadako Yamamura (Rie Inō) raking ten bloody fingers sans nails across the tatami. Given her video-made-real M.O., it seems appropriate that Ringu should be one of those movies where you can relive moments from it offscreen.

Up the Hill to Horror

When we first see the cabin in Ringu, Nakata and cinematographer Junichiro Hayashi fetishize it with a series of POV shots that put the viewer in the perspective of investigative journalist Reiko Asakawa (Nanako Matsushima). First, she comes walking up the hill to behold the cabin’s face, its white curtained mouth, and two trapezoidal black eyes, staring out from between logs like The Amityville Horror house. In a 2000 interview with Offscreen, Nakata admitted, “I was influenced by the Amityville series of horror films,” and that shows in his choice of windows.

As Reiko eases up on the cabin’s doorstep, we share the dread of what she might find in there. It’s a dread that has built since Ringu’s opening scene, which gives the cursed video the flavor of an urban myth as Reiko’s niece, Tomoko (Yuko Takeuchi), and her friend sit discussing it at a sleepover. The date onscreen is September 5, and Tomoko reveals that she stayed somewhere and watched the video there with friends a week beforehand. Later, after Reiko gets the photos of their trip developed, we see a picture of Tomoko and her friends in front of the cabin. As a side effect of the curse, their faces are distorted, but the date August 29 is stamped in the corner.

Using the photos as her guide, Reiko tracks down the cabin herself, and it acts as the key setting where she, too, watches the video and eventually returns to unearth the vengeful Sadako’s wet corpse. Because it’s not so far from where I live, I did a similar thing (minus the wet corpse). Using movie screenshots, Reddit, and Google Translate as my 21st-century guides, I tracked down the cabin and stayed there on the same date the movie’s first teen victims did. It was 25 years after Ringu first hit theaters in Japan, and I was alone for the night.

Where Taxis Fear to Tread

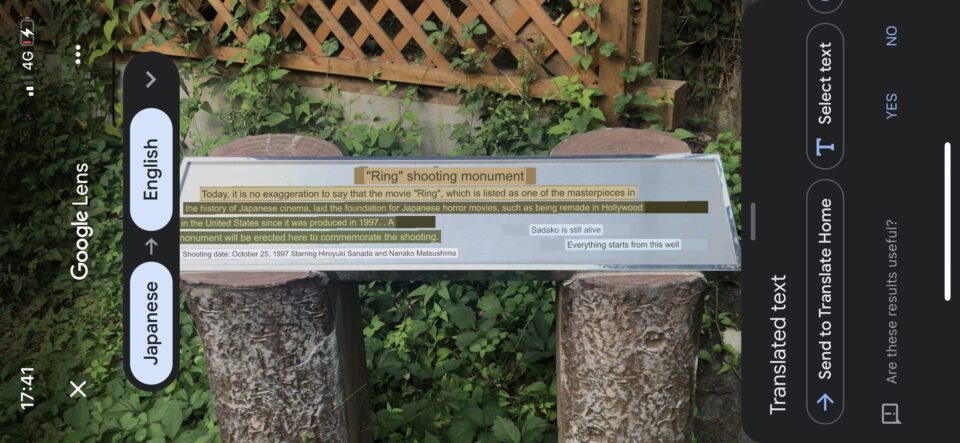

America Camp Village still advertises cabin L-6 as the one where Nanako Matsushima and costar Hiroyuki Sanada shot scenes for Ringu. The filmmakers put two signs up out front changing the number to B4, but near the weedy crawlspace under L-6, there’s a monument in Japanese commemorating the cabin as the filming site.

Though it beckoned to me, I couldn’t convince my horror-averse spouse to come along on this camping adventure and commune with Sadako’s spirit in the cabin. We had already visited the famous Himeji Castle in Hyogo Prefecture, where you can find the true-life well said to have inspired the fictional one Sadako haunts in Ringu. On your way out of the castle complex, you can stare down the well, though it has a stone fence around it and a metal grate over it, and it isn’t necessarily as Instagrammable as the rest of the main architecture.

After a two-hour train journey, one that took me deeper into the mountains than I would have ever thought possible in Tokyo, I soon learned that America Camp Village is a place where taxis fear to tread. There were no cabs idling in front of the station like there would be in the more urban and suburban parts of Tokyo. I saw the numbers for two local taxi services posted by the empty cab stand, but when I called them and made a bumbling attempt at summoning a ride in Japanese, it seemed like they weren’t able (or willing) to go to the campground.

One cabbie who refused me already knew where I wanted to go and finished my sentence for me before I had even spit out the name America Camp Village. That’s exactly the kind of thing you’d expect to happen in a horror flick like Friday the 13th, where the locals were leery of a campground that was a kill zone. Maybe he had dealt with a lot of doomed movie tourists.

Across the street from the train station, I did see a bus stop, but the campground’s website said nothing about bus access except that it had a shuttle bus that was currently out of commission. Just days before I visited, it had entered the off-season, which again made my overactive horror imagination think of Stephen and Tabitha King being the only guests at the Stanley Hotel on the very last day of ski season. Since I didn’t know the area, and since the campground looked easy to find on Google Maps if I followed the Tama River, I decided to walk.

Ringu Come to Life

America Camp Village is rather far on foot from the train station, but the mountains and river gorges make Okutama a scenic walk during the day. In Ringu, Suzuki’s original male book protagonist, Kazuyuki Asakawa, is also a reporter who is eager to visit “the actual place” yet darkly imagines “the perfect Friday the 13th scenario” as he heads for the villa log cabins at South Hakone Pacific Land (changed to Izu for the movie). When he gets there, he finds the manager in an office with a shelf full of videotapes that include that film and other horror titles: The Legend of Hell House, The Exorcist, and The Omen. It’s as if Suzuki already anticipated the potential for his story to join the ranks.

As for America Camp Village, it’s more like the Japanese remake of a U.S. campground, with a small general store and the façade of other Old West-like buildings lending the site its faux “village” component. The retro shuttle buses are even painted red, white, and blue. Seeing a couple of them parked under an abandoned-looking carport down the street from the campground’s entrance, they struck me as the kind of creepy old ‘70s buses you might see sharing the road with the period vans of X and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

The campground itself runs alongside an unnamed river or tributary of the Tama River, where I could see kids playing as I entered. However, this wasn’t quite Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco — better known as Camp Crystal Lake, the hunting ground of Pamela Voorhees. The cabins at that real New Jersey campground are now a place for Boy Scouts (literally), though you can still visit the place on horror-themed tours. America Camp Village, on the other hand, is a campground where Japanese families and teen groups (possible slasher or Sadako victims) can often be seen barbecuing and sitting on picnic tables outside their cabins. Today, they were joined by one stray foreigner prone to morbid flights of fancy. Maybe I was the movie monster.

As I checked in and picked up some food at the general store, I experienced another scene straight out of Ring and Ringu. In both the book and the movie, there comes a moment where the manager expresses surprise that the journalist is checking into the cabin alone. In the movie, he says, “You’re here alone?” And Reiko says, “Yeah, I’m doing a bit of work.” But in the book, he says, “Just you, then?” He’s even more suspicious, actually, because he’s never seen anyone stay there alone.

I don’t know if they just misread my reservation for one and added a zero, but when I checked in, they were also surprised that I was alone. It soon became apparent that they were expecting ten guests in the cabin and had prepared it accordingly.

Inside the Cabin

As I walked up the same hill that Reiko did in Ringu and rounded the corner to cabin L-6, I immediately noticed that the wood was a darker shade than it was in the film. I took some pictures of the front of the building, comparing it with movie screenshots saved to my phone, the way Reiko compared her niece’s photo with the cabin.

When I went to unlock the front door, I saw a small chunk of wood missing from the frame, right near the deadbolt lock. It almost looked like someone had tried to jimmy the lock open. My mind continued to map the permutations of every possible horror movie connection. Cross-reference the home invasion in The Strangers.

False alarm: There was no one waiting to ambush me when I opened the door. I put my backpack down and scanned the spacious common room the way the camera in Ringu did. It was definitely the same room, but the furniture was arranged differently and there was no couch or wooden support beam in the middle. Instead, there was just a long, low table, perfect for a cult of ten people (nine of them perhaps uninvited guests, looking to groom yours truly as a human sacrifice). The closet had ten futons ready, and as I settled in under the vaulted ceiling, I wondered if the cabin had been chosen as a shooting location in part because it was big enough to sleep a small film crew.

I would only need two futons. (The floor was hard, so I decided to double up.) Cabin L-6 had no landline, VCR, or even a DVD player. But when I turned the TV on, I was able to get static on one channel so that it looked like the TV in Ringu. This was just for effect, as I had brought my laptop with me and planned to watch a downloaded iTunes copy of the movie.

The mundane reality of the cabin during the day turned spookier at night when its windows came alive like glowing eyes. America Camp Village closes its front gate at night, so I felt a little like I was locked in with Sadako as I curled up on the futon to watch Ringu. Before that, I was able to confirm visually that the cabin was not, in fact, built on top of a well. Yet inside, on the wall under the stairs, there were two mysterious locked doors, one long and slender, the other short and squat. They were probably just storage closets, but the way they were spaced in relation to the concrete foundation under the cabin, it seemed possible there might be stairs on the other side of those doors, leading down to a hidden well that the owners had wisely walled in.

As I watched Ringu and looked around and saw myself sitting in the same room, I imagined one of those locked doors creaking open.

Alone with the True Sadako

Sadako never came to attack me in my fitful sleep that night, but as I kept an eye on the two locked doors and imagined her subterranean lair below the cabin, I did have time to ponder Ring and Ringu’s prescient subtext. In Robert B. Rohmer and Glynne Walley’s English translation of Ring, published by Vertical, Suzuki writes of a “pestilential videotape” that “would no doubt spread throughout society in the blink of an eye.” Keep in mind that the novel was first published in 1991, pre-internet for most households. “Driven by fear,” Suzuki writes, “people would start to spread crazy rumors.”

Ring and Ringu not only set off the J-horror boom but also gave bloom to a lucrative media franchise. They also predicted with chilling accuracy the shape and tenor of the viral news century to come. Of all the movie and TV adaptations, it’s still Ringu that comes closest to the full portentous scope of Suzuki’s original prose ending, in which Reiko’s gender-flipped counterpart, the ill-fated newspaper reporter, Kazuyuki, races against time down an expressway where black clouds slither “like serpents, hinting at the unleashing of some apocalyptic evil.”

Reiko, too, is a journalist—and mother—and it’s to save her son that she drives toward the mountains with dark storm clouds overhead at the end of Ringu. She’s on the phone with her father, and she intends to show him the cursed video, which Sadako’s dying rage recorded through psychic photography. Remember, it needs to be copied and spread like an audiovisual chain letter, or else the viewer will die. That doesn’t bode well for Reiko’s father or the rest of human civilization.

Three years before moviegoers first saw that final image in Ringu, Douglas Rushkoff’s book, Media Virus: Hidden Agendas in Popular Culture, created a modern framework for the discussion of memetics, a concept that feels very much of a piece with the spread of cursed images in the movie. In his 1995 preface, Rushkoff cited a Ringu-like image—that of a car moving along a road—as the first time in media history that people did a reverse Sadako and walked “onto their own television screens.”

He was talking about the 1994 police chase of O.J. Simpson’s white Ford Bronco across Los Angeles, which prompted L.A. residents to leave their living rooms and become live spectators on national TV. The footage of that moment, captured by helicopter, was something Rushkoff likened to a contemporary Zapruder film, bringing us into a new era of audience participation, where heroes could be “exposed as false idols” as new media expanded its potential for instant gratification. This gels with the passage in Ring where Suzuki describes the nightmare image of an angry mob of faces, “painted on a flat surface” and “existing only from the neck up.” It’s a multitude of talking heads, “tinged with criticism, abuse.” It’s cable news and the internet, coming for you and everything you hold dear.

Eaten by the Lost

Rushkoff’s pre-YouTube metaphor of people walking onto their TVs almost guessed right out the climax of Ringu, where Sadako crawls through the screen to kill Reiko’s ex-husband, Ryuji. That specific murder method was a cinematic invention, not found in the book. It was the movie that allowed Sadako to use screens as a portal into our world.

In 1991, Suzuki wrote of a planet where people might be “subconsciously infected” by Sadako’s curse, as if she could poison the whole world’s well. Back then, the founding of Twitter, public awareness of the idea of memes, and popularization of the phrase “going viral” were over a decade off. When Suzuki wrote of a video flashing, “You will be eaten by the lost,” could he have known how much our culture would relish cannibalizing itself in the new millennium?

Twenty-five years later, in a campground on the outskirts of Tokyo, I rented out the cabin where Ringu was filmed and watched it there. Alone in a room with a screen in front of me, I saw that the movie remains on-brand for the world we live in. Harrowing as it was, I feel confident that I survived the experience because it’s been well over a week since that night. Sure, seven days is a shifting goalpost in the franchise, but it’s only a movie, right?

Hang on, the phone is ringing. I’ll be right back.

Categorized: Editorials