Mandatory Fear – The Dreadful Whipping of Castlevania

Mandatory Fear is a look back at the vital entries in horror gaming, exploring what made them effective at scaring us and their importance to the history of the genre.

Horror games in the 80’s had their work cut out for them, visually. Not that games like Sweet Home weren’t doing incredible work creating gruesome, unsettling sights with pixel art, but it was still a challenge to create something that would frighten the player. Even with the above example, it only really all came together from a mixture of sound, visuals, and mechanics to create something chilling.

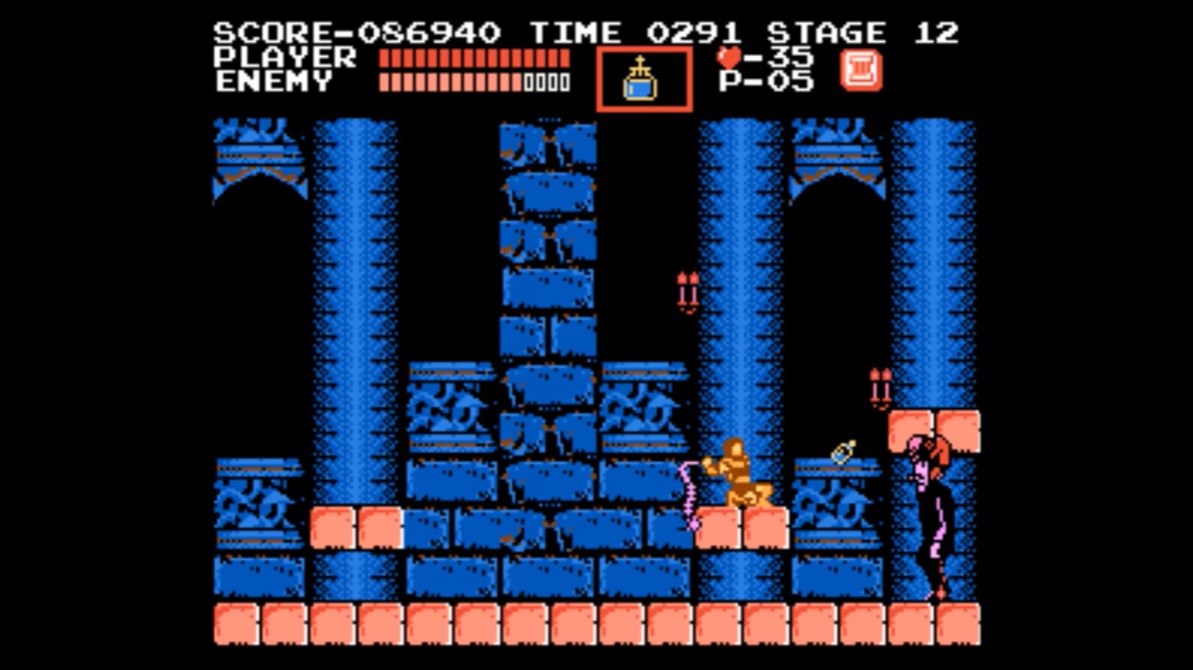

Castlevania had a similar challenge. Don’t get me wrong, its pixel art is pretty sharp in many places. There are some designs that look pretty gross and eerie, but for every solid enemy or environmental design, you get a goofy-faced bat boss or irate cat-thing. So, how do you make your game feel a little more frightening when your art isn’t quite enough to make players quiver with fear?

Turns out, you make one little mechanical choice that affects the entire game in ways that teach the player to approach each situation with caution and, perhaps, a bit of unease. Well, maybe a couple of choices.

Castlevania chose to add a little wind-up motion when you attack a monster with your weapon: the whip. You have to cock your arm back before you strike with your whip, something that adds a few millisecond delay any time you want to hit something. Many other games of the time would have you leap or shoot of stab the instant you hit the button with little wait time, assuring you can react quickly to a change in your combat situation. In this game, you need to know when you want to attack a little bit in advance, and if something surprises you, you’re vulnerable for a precious few moments before you can lash out.

This seems a bit aggravating coming off of Contra or Ninja Gaiden, as those games allow you to hit foes quickly. Even if, say, some awful, terrible, hateful bird comes swooping down at you when you’re leaping over a cliff in Ninja Gaiden, you can smack it away with a quick button press (not that those things haven’t sent me tumbling down pits a few thousand times). If an alien soldier gets up in your face in Contra, a tap of the trigger button will mow it down. It’s instantaneous, and allows for very twitchy reactions when you need them.

So, to find yourself trying to attack, only to have to wait a few moments for it to actually strike, felt offputting. It was irritating because it meant you’d often get hit while trying to smack something that got the drop on you. Your timing would have been fine in most other games, but for some reason, Castlevania chose to throw in this enraging delay in your attack, so now you got hit. And if you’ve played this game, you know how few hits you can take before you’re dead and sent back to the beginning of the area.

While this mechanic might initially make you bristle, it’s something that teaches the player to respect and fear the enemies that they’re dispatching. Even something that only needs one hit to kill requires you to take care with your timing as well as your aim, only striking exactly when everything has aligned properly. Enemies suddenly aren’t as disposable as they are in other games, as each needs to have their movement speed and actions factored in very carefully when considering when to use your whip.

What’s scary about that? Well, instead of enemies being these obstacles for you to chop or blast down as you rush through the level, each foe is now something to be observed and approached carefully. You have to really study their movement speeds and actions, as you only have a specific range and attack window to hit it in. Other games might have a shorter attack range, but the ability to strike with no hesitation means you don’t have to be terribly careful once foes get in close. Castlevania, on the other hand, makes enemies extremely dangerous the closer they get to you, as you have very little time to react.

Creating fear with mechanics is a neat choice that deals with the visual “limitations” of the era, and it’s something you see in use even now when the developer wants the player to feel something unique from the game. Take The Last Guardian, for example. In it, you’re working with this cat/bird/dog creature (Trico), asking for its help to solve puzzles and explore. The creature doesn’t always follow your instructions as well as you’d like, which, from a player perspective, could be seen as annoying. However, if you’ve ever trained a pet, you know that they don’t always listen, either.

As such, this mechanic is used to drum up similar emotions as the player might feel while training and bonding with a pet. It seems odd to have something ignore your commands in a gameplay setting, as it doesn’t seem like smart design, but it’s the emotion that’s the vital part of what’s being built. It’s why I have such strong memories of my time spent with Trico, and why some of its heartbreaking scenes really stuck with me.

Castlevania uses a similar design philosophy to make you fear its pixelated enemies. That whip delay makes you really appreciate its foes as they come lumbering your way, as you really, really need to know what they do. Zombies are slow, but often attack in numbers, meaning if you strike too early with your whip, you might kill one but miss the creature behind it, leaving yourself open. With the Medusa Heads, you have to gauge their swooping movements to land a hit, with a miss often meaning a tumble down a cliff. If you’re finding Flea Men raining down on your head, you’ll want to get close and strike fast to avoid dealing with their erratic movements.

So, you take a good, close look at these foes as they creep close. You get to appreciate the twisted, decaying features of the zombies as they move closer. The mangled, smirking faces of the Flea Man as it prepares to leap around. The scowl on the Medusa head, the vacant eyes of the Merman, and Death’s near-smile on its skeletal visage all seem to burn themselves in your memory as you really need to take them in as you study their movements. I couldn’t tell you many of the features on most enemies of the era unless I played the game dozens of times, but I can recall so much about the design of each Castlevania enemy because of how important it was to know everything about each foe. Not just the challenging enemies, but every single one of them since each was a very real threat due to that delay when you swing your whip.

And when just about anything can kill you, you learn a certain fear for them, don’t you? Each creature in the game can, near its end, down you in a handful of hits. Nemesis in Resident Evil 3 can’t even manage to take me out in so few attacks (thanks to healing herbs), meaning every basic enemy in this game can be just as threatening. But in Resident Evil 3, I’m limber and mobile, whereas in Castlevania I can only move slowly and attack when I have a few milliseconds to breathe. My options are limited in the latter game, so every enemy brings a little bit of terror along with it. I have every reason to be afraid, too, as I can’t make many mistakes and still survive. Healing isn’t likely to happen, either.

So, every time an enemy rears its head, no matter how basic, there’s a twinge of fear. A little anxiety as I watch its movements and try to figure out the best time to attack. There’s this tension in the air as the monster closes the distance, all while I wait to hit the thing with the proper timing. I’m forced to stare it down, taking in its every gruesome pixel, hoping that some new creature won’t appear to add even further danger.

I’m in appreciable danger from every enemy in Castlevania because I can’t just clobber it and move on. I have to wait and prepare, taking agonizing seconds watching my enemy and praying I don’t miss, losing a precious chunk of health from a hit or getting flung off a cliff, losing an even-more-precious life. You get to learn to be a little bit afraid of these monsters as a result. Maybe it’s not the same fear I get while avoiding the unsettling creatures of Amnesia: The Dark Descent, but I’ve been taught to feel some terror at the thought of these monsters getting close. It’s beyond impressive that this is largely done through a single mechanical decision.

This isn’t even factoring in the clever groups that the game throws at players. An axe-throwing Knight is a lot to deal with, but what if you’re also trying to hop around Medusa Heads that are flying around the hurled weapons? A bat isn’t much trouble, but when you’re trying to whip one while leaping across floating platforms and weaving around Mermen trying to knock you into a pit, things get quite challenging. As always, the game uses the most basic of foes in clever ways that ensure they always feel a bit intimidating and fear-inducing when they show up.

You might be thinking that there are sub weapons in the game that help you work around the challenges of the whip’s design, and you’d be right. Castlevania lets you pick up axes, daggers, throwing crosses, stopwatches, and holy water, all of which have different attack properties and can be used much quicker than the whip. So, shouldn’t these take away that fear you feel when encountering monsters?

Well, not really. For starters, you lose whichever sub weapon you have when you die, so until you’re very good at the game, you won’t be able to keep your sub weapons for long. They’re unreliable tools, and until you’re extremely skilled at the game, I’d argue that you tend to get stuck with whatever’s available. The weapons are strewn about the game in odd places, so you don’t have much choice in what you get, often having to work with whatever you pick up. This means that you’re slave to the ranges and attack styles of what you pick up.

Each one does offer a varied striking range. Daggers fly straight but are weak, holy water flies in an arc and leaves a damaging flame on the ground for a few seconds, the axes fly high up and then down, the cross moves out then comes back (boomerang style), and the stopwatch is garbage and you should get something else. They all have a style that you need to know well, even if they do attack faster.

You can still use them in a pinch, so what’s the worry? Well, they use up ammo, which is hearts you can collect from smashing candles throughout Castlevania. You usually only have a few uses of each weapon, so you have to decide when they’ll be the most help. Having a good supply of sub weapons for bosses is always a solid plan, but that means saving them during the level. You have to carefully consider whether you want to use a sub weapon in each situation, adding further tension and strategy to each enemy approach.

If this idea is sounding familiar, it’s because it draws from a similar item scarcity that many future horror games would draw from. Knowing you can run out of your killing tools makes each encounter with enemies a bit more chilling, as you don’t know if you’re wasting your weapons when you’ll need them later. You’re encouraged to take risks and save your weapons because you don’t know what’s ahead, putting yourself in more danger than you might need to. Or will you leave yourself empty-handed during a challenging boss if you’re too free with your weapons early on?

While the sub weapons help, they can only do so much, and even the thought of using them comes with a little tension that, again, adds some fear to even the smallest of foes. Should you waste a few crosses on that Medusa Head before it knocks you off a cliff, or will you need each one against the boss? What’s the right thing to do in your situation?

So, when Castlevania’s basic zombie comes creeping toward you, you pause. You hesitate and study the situation, gauging movement speeds, enemies on-screen, and your available tools. You have to really drink your foe in, and let yourself feel a twinge of fear at what will happen if you mess up any of these details. It takes far too few mistakes to die in this game, so each enemy is cause for alarm. Other games would have you mowing creatures down without losing a step, but this game makes every enemy a threat – one you might feel just a little bit afraid of.

And this largely stems from that whip timing mechanic. In other games where you could strike at will, you could afford to come close to making a mistake, but in Castlevania, your timing has to be pretty precise, and your attack launched in advance. You have to creep carefully and strike with precision, resulting in an experience that conveys a fear of its foes based on how dangerous they are and how hard it is for you to deal with them.

A sense of helplessness without preparation. An inability to react when surprised. A lethal end awaiting an error in judgement. They’re basic versions of these elements, but they all come together to make the player feel fear. Maybe not the sort of stuff that has you looking over your shoulder at night, but a kind of fear that is incredibly impressive given the limitations of games at the time.

Categorized:Editorials