MEET SNET, CUBA’S HOMEGROWN GAMING INTERNET

Welcome back to HISPANICS IN GAMES! Starting 2021 has already been a bit of a struggle, but today, I am the bearer of good news: this column will now be coming out weekly! We will bring you more features, interviews and editorials, positively highlighting Hispanic heritage within the video games industry. As for this week´s feature, it is a juicy one. If you´re old enough to remember when multiplayer meant you and your friends in the same room, rather than people all over the globe, you´ll know what a LAN party is. And if you´ve been reading this column for any length of time, you´ll know that Latin America has had its fair share of dictatorship interference on video games. In Cuba, these two topics merge in one of the most ingenious feats of engineering you´ll ever see: SNET. Join me today, then, to learn more about Havana´s massive, city-wide LAN party.

SNET CONTEXT AND ORIGINS

Before jumping into what SNET was, we must first understand why it came to be. From 1953 to 1959, Cuba underwent a revolution led by Fidel Castro. Ever since then, the little island has been an isolated ecosystem, particularly when it came to Western, ¨capitalist¨ technology.

So, while the while the rest of the world rejoiced in the wonder that was the internet in the 1990s and 2000s, Cubans remained, for the most part, isolated. To this day, official internet access is restricted to public hot spots in city squares. And even then, it is a costly proposition. Not only that, but you are also restricted in which sites you can access, and your traffic is monitored by the government.

Not really an environment which breeds online gaming, is it? Apparently, the good people of Havana thought the same. They saw that people in other countries were able to play video games with, and against, each other. And they saw that it was good. Without official access to the internet, however, what could gamers do?

Enter SNET.

COMMUNITY: THE SNET ETHOS

Nobody quite knows who started SNET (which stands for Street Network). Legend goes that it was Cubans who had gone out to the wider world, and brought their knowledge to Havana to liberate gamers.

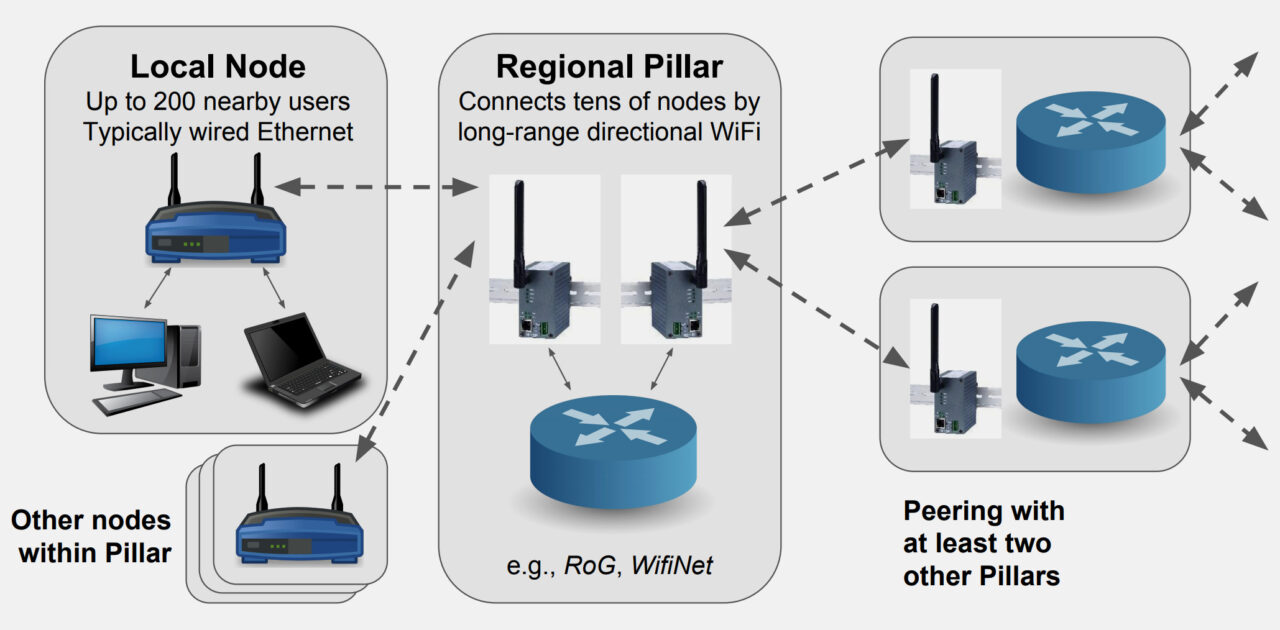

Seeing that Cubans had no way of enjoying online gaming, these early pioneers developed a network which allowed gamers in Havana to connect with each other via wireless clients spread out across the city.

In true underground movement fashion, community was at the core of how SNET operated. For example: when joining SNET, you had to allow your node to be an anchor point for other clients, too. You had to allow traffic both ways, and ensure that other people could connect to your setup. This extended the network, decentralized access, and built multiple points of failure, which ensured network stability. If one client failed, then others took up the slack.

THE COST OF RUNNING SNET, AND WHAT YOU GOT FOR IT

Unlike Western internet service providers, joining SNET was be a pricey endeavor. Not only did you have to pay for the hardware to set up the node (from US$200 and up), but you also had to pay a fee to whichever admin group your node belonged to.

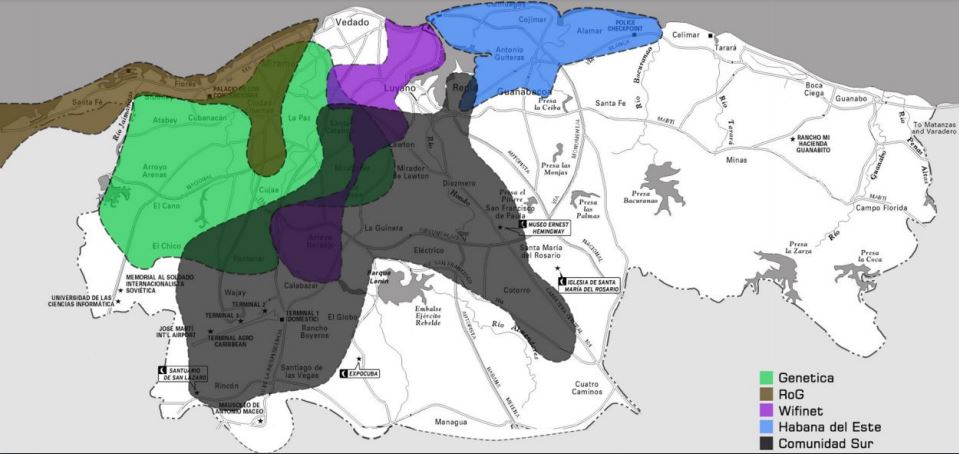

There were a total of 9 admin groups at the height of SNET, all vying for users and their fees. Each admin group could host between 60 and 200 users.

There was a list of do´s and don´ts to using SNET as well. For the most part, playing video games online was the defacto use, and for this purpose, modified versions of popular games were made to work with SNET´s infrastructure. In particular, World of Warcraft had a substantial userbase. But any political activity was banned from SNET, and using the network for such purposes would land you in serious trouble, both with admins and the government.

Overall, though, it was live and let live between SNET users and the notoriously strict Cuban government.

Until we came along.

COVERAGE, CRACKDOWN AND REFORM

In 2017, SNET got wide international attention thanks to a feature by the Associated Press. Over the next couple of years, a plethora of Western media outlets would write about SNET, interviewing its administrators, and highlighting the surprisingly relaxed attitude of the Cuban government toward it.

It all came to a head in May of 2019, when the government legalized data networks for use by natural persons (humans, basically, rather than institutions). What this did, in reality, was outlaw and restrict wider SNET useage and administration by its admin groups. It restricted as well the initiatives by a few admin groups of incorporating digital storefronts into SNET, allowing users to buy access to games and customization items for games such as WoW.

In August of 2019, SNET made a landmark move by getting merged into the Joven Club de Computación y Electrónica (Young Club of Compututation and Electronics). The Joven Club, an institution created by Castro in 1987, had official government backing (as well as regulators).

There were 600 such Clubs around Cuba in 2019, and they would become the main nodes of SNET moving forward. All other nodes in the network would become subnodes, dependent on their main Joven Club nodes respectively.

The move took place among historical, peaceful demonstrations, and in the space of a weekend, two and a half decades´ worth of underground network infrastructure were merged into the government ecosystem.

CURRENT STATE OF AFFAIRS

The absorption of SNET into the Joven Club has allowed the initiative to get government support, which in turn has allowed it to reach a much wider set of users.

The changes are recent, and it will take time to see how democratized the initiative becomes outside of Havana. It also remains to be seen how much government interference takes place within the network.

The Cuban government has already started programs aimed at providing rental equipment to people who don´t have the funds to buy the hardware upfront. But it has also started to implement network-wide control and there are official government overseers ensuring the proper use of the infrastructure.

The Joven Club network is also miles behind international standards in terms of technology and equipment. It even lags behind SNET itself, often creating bottlenecks or the necessity to jerryjig a solution to interface the two.

As the continued history of SNET develops, its community-focused, decentralized model is being adopted in other countries, too. Argentina and México already have similar infrastructures which allow people in remote areas to access the world wide web (or parts of it).

Uncertainty looms over SNET´s future. But the incredible feat of engineering which allowed it to exist will forever endure as a testament to Cuban inginuity, and the desire to communicate and socialize which is hardwired into our makeup as human beings.

Categorized:Editorials