Red, White and Boo: Are we not yet sick of American horror games?

Have we ever used the phrase ‘cultural hegemony’ on this site? It may sound like one of those phrases for those who get laid a lot in college (as Rick Sanchez might put it), but God damn if it doesn’t describe the games industry’s relationship with the USA. And it’s so painfully boring. Worse still, when it comes to horror, the results are games that just aren’t all that scary.

Let me back up a bit. This all started when I was reviewing Remnant 2. I quite liked Remnant; it’s got a good core gameplay loop and some neat visuals, even if its approach to storytelling is a bit lacking. But one moment that really ground my gears was the character creation screen. Or specifically, the voice selector.

The Remnant series is set in a multiverse threatened by The Root, which is basically Warhammer 40,000’s Tyranid faction with a botany fetish. The Root reaches Earth and wipes out 99% of humanity, leaving only a handful of hardened survivors. Twiddling the sliders on my particular veteran, I was invited to choose one of six voices for them. Given that they’re supposed to be one the few remaining humans left on the entire planet, you’d have hoped that perhaps there’d be a bit of generosity when it came to representation. After all, there are (were?) quite a few of us on this small blue dot. Sure, you couldn’t do all 195 countries, but maybe one from each continent? North and South America, Asia, Europe, Africa, Australia, Antarctica – but replacing the last two for some nation with a significantly larger headcount. Sooo… going by population, how about an American accent, a Brazilian accent, a Chinese accent, a German one, a Nigerian one, and an Indian one?

Not a jot of it. Instead, the choice was solely between six generically grizzled American accents. Six. And I was damned if I could tell the difference between half of them. Then I remembered the first game, and how the post-apocalyptic Earth biome was relegated to a single destroyed American city. It was literally called ‘Earth’ too, and not ‘Boston’ or ‘Chicago’ or wherever. With all our world’s myriad cultures, countries and geographies, the game predictably chose to limit itself to a few square miles of urban America. Well, that’s not entirely fair: a piece of DLC later expanded its scope to include a single destroyed American farm as well. Whoo – way to push the boat out there, guys.

You could say this is being nitpicky. You could say it’s trying to make a broader point whilst spending nearly 500 words ragging on a single game. You could also say it’s banally stating the bleeding obvious. We all know that the majority games with a real-world setting take place in America, or feature American protagonists. Pop culture, as wits like to point out, is the USA’s biggest export. But the mark of the truly successful cultural force is one that’s so widespread that it’s not even talked about. It’s just considered the default position.

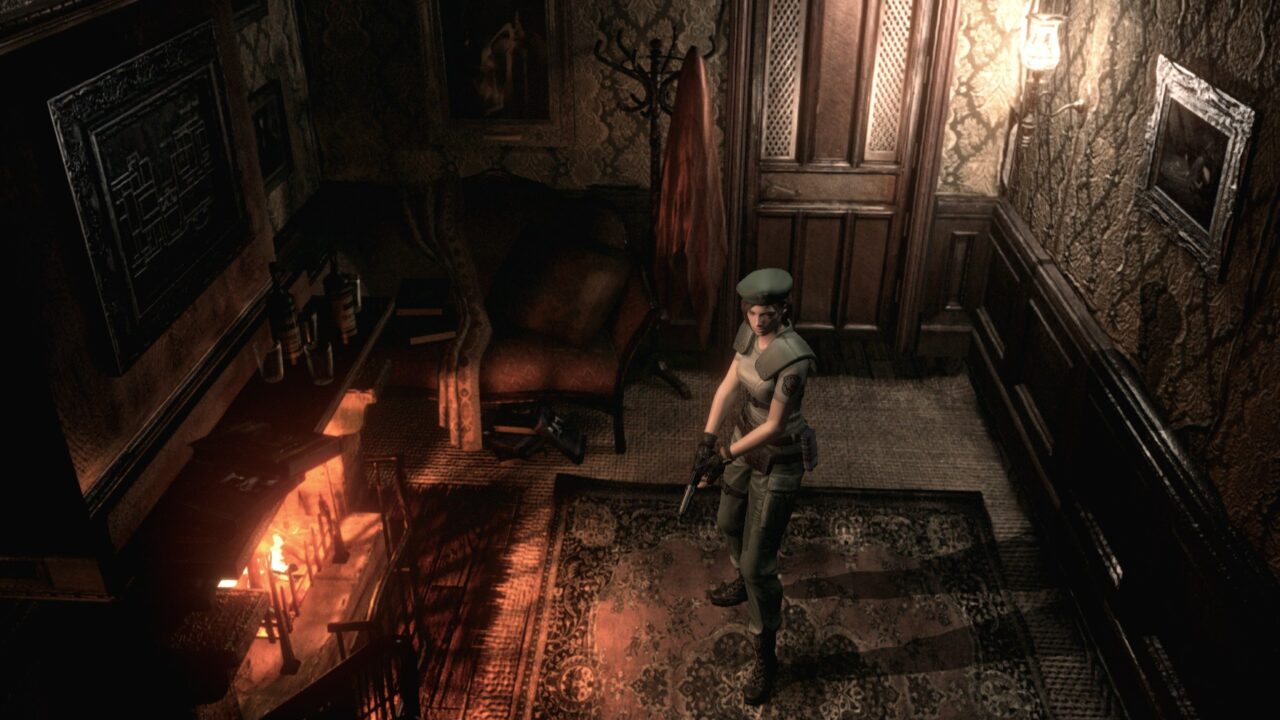

I was thinking along these lines when I switched to Daymare: 1994 Sandcastle. Made by Italian developers Invader Studios, it’s the second entry of a survival horror series that started life as a fan remake of Resident Evil 2. The story is so boilerplate it’s almost parodic: a US special-forces type investigates an underground research facility that’s been experimenting with bioweapons. Que zombies and shady government/ corporate cover-ups. The situation’s nuts here. Remnant’s developer Gunfire Games is at least based in the US (although with a name like Gunfire Games, frankly they’d have to be). But with Daymare, you’ve got a European developer making a game set in America that’s imitating a game made in Japan that’s also set in America. Damn.

You could argue that it’s simply a financial calculation. This is a valid point. America is the largest consumer and maker of videogames, at least according to my admittedly cursory internet digging. And I’m guessing that games companies do their market research. Presumably, when Capcom signed off on Resident Evil in the 1990s, the USA was by far and away the largest consumer market. It made sense to appeal to American tastes first and foremost. With gaming exploding in popularity across the world since, the playing field has probably become a bit more level. China’s consumer market, I believe, closely challenges the US’s, while other countries have narrowed the gap at least somewhat.

But honestly, I think you’d be hard pressed to claim that decisions about where to set or who to star in games are only a financial calculation. Frankly, I’d be surprised if the decision to go American hasn’t simply become reflexive at this point. I’m reminded particularly of Deadlight, the 2012 zombie game by Spanish developers Tequila Works. In a making-of video they talk about why they chose to set their game in Seattle. The answer was for no other reason than that America has all the most familiar zombie tropes. Things, it seems, have a habit of generating their own momentum when they become large enough.

Let me give my perspective as a Brit, for whatever it’s worth. I find it easier to imagine horror games set in contemporary America than I do in my own country. There are a few vestigial reasons, sure. Britain is a small, incredibly densely populated island nation, so it’s hard to find a location with any real sense of isolation. Strict gun laws mean that there aren’t many firearms knocking about. Existing games that take place in the UK are almost invariably set during the Victorian era, not the present day.

But this is beating around the bush. Because when I mean contemporary America, what I really mean is the America of the screen. It’s the world where trench coat-wearing PI’s sleuth through sleepy towns hiding dark secrets. It’s where crazed hillbillies chase horny teens through cornfields. It’s where the helicopter arrives right as the zombies break down the doors.

And the problem is that none of these are truly horrifying. They’re hallmarks that have become tropes that have descended into clichés. Lovecraft himself (a New Englander) wrote that the greatest fear is fear of the unknown. Yet you have to go a long way to get that currently. I want to see horror games set in my own country, sure. Primarily, I just want to see some horror games not set in America. I want to see horror breaking new ground and doing away with stale ideas. Horror’s duty as a genre is to perturb, not pacify.

But what do you, dear reader, think of all this? If you’re a non-Yankee, does American horror scare you? Does it have a sense of the alien or uncanny about it? I rather doubt it. What about those of you who actually do live in America? After all, I’m guessing you make up the bulk of those who’ll be reading this. Do the familiar references scare you, bring you comfort, or have they become stifling? How many more times do you want to face sackcloth-wearing chainsaw rednecks, or aliens invading New York, or Cthulhu threatening a town in a flyover state?

I’ll be real. One small guy like me writing trite arguments like this isn’t going to shift the industry. America remains top dog in the videogames market, both making and consuming them, with its only close competitor being China. China doesn’t even really have a AAA developer space as such yet. With Beijing’s heavy censorship laws, I doubt horror would have much of a chance. And besides, sticking with the familiar is a hard habit for players to break. I get it. Hell, a horror game without guns needs to really hook me before I even touch it. But chuck in a shotgun and you’re practically halfway to a sale already.

Yet videogames are an ever-changing medium. Right now it’s one in crisis. Johnny AAA has gotten himself into an untenable position as he tries to pump out ever bigger and shinier games that collapse under their own weight. Design by market analysis and fruitless trend-chasing has left gamers crying out for originality. We want genuinely good games, not the same old microtransaction skinner boxes that keep getting shoved down our throats.

So I want to put out a call to action. The time is right to do away with the current model, the same old tropes, and the same old boringly attractive, quippy American protagonists. Bring on those auteurs, those bold new creators who are prepared to see beyond the myopically narrow lens of existing models and structures. If games want to innovate, and if horror wants to scare, it’s going to need developers who can tell us stories from other lands, other peoples.

There are some wildly creative non-American horror games currently out there, even if they’re rare beasts. There’s the Little Nightmares series from Swedish developer Tarsier Studios, which uses a twisted early 20th Century industrial European aesthetic to create unease. Konami’s Fatal Frame series explores feudal Japan to deliver the stuff of nightmares. Prague-based developer Spytihněv recently gave us Hrot, a surreal Soviet boomer shooter set in Czechoslovakia. Ukrainian developer Action Forms creates psychological horror aboard a nuclear icebreaker in Cryostasis: Sleep of Reason, while the Polish Acid Wizard Studios weaves a macabre fairytale with Darkwood. Red Candle Games brought us Devotion and Detention, titles I consider two of the best story-driven horror games ever. The list goes on.

A lot of these are indie endeavours. Most of them lack the budget of a modern AAA studio. Yet it’s the outsiders who so often shake up the formula, and these are the kind of developers we need more of. Hail to these chiefs, I say, whichever country they may come from.

Categorized: Editorials