Night Shifts: How ‘Five Nights at Freddy’s’ Started a Terrifying Gaming Trend

Whenever people think of horror games, they think of the adrenaline-pumping chases in Amnesia: The Dark Descent, the suffocating psychological horror of Silent Hill, or the infamous B.O.W.S. of Resident Evil. However, a particular motif has become increasingly popular since the 2010s, all thanks to one game.

Whether you loved or hated it, Five Nights At Freddy’s forever changed the world of horror games. While Amnesia: The Dark Descent and Slender paved the road for indie horror, Five Nights At Freddy’s strapped a rocket to the genre’s mainstream popularity.

Five Nights at Freddy’s impact on modern pop culture can’t be understated. People will assign its success to the creepy animatronics and convoluted lore, but one element ties them all together. The franchise made its name with what I like to call “maintenance horror.”

Mundane Made Murderous

Let’s first define maintenance horror. This subgenre is one in which the fear stems from the player’s ability to perform mundane tasks. Admittedly, it’s a bit dishonest of me to pin the success of maintenance horror solely on Five Nights at Freddy’s.

Once you strip survival horror’s gameplay loop down to the basics, it’s about gathering items, managing resources, and avoiding enemies. You can see this best with 1981’s AX-2: Uchuu Yusousen Nostromo, one of the first survival horror games ever made.

The game traps the player in a spaceship with a hostile alien, and they must find a certain number of items to escape alive. Over three decades later, Alien: Isolation would perfect this exact formula. It’s a fitting bookend, given the namesake Nostromo came directly from 1977’s Alien.

Dead by Daylight’s entire gameplay loop can be summed up as running away, hiding, helping survivors, and fixing generators. The tension comes from how well you perform those tasks. Even one screw-up may cost the team a survivor, lessening the odds of survival.

Inventory management is another manifestation of maintenance horror. Resident Evil deserves praise for making resource management inexplicably fun in Resident Evil 4. The limited inventory forced players to think before they scavenged every item they saw.

Amusingly, watching CCTV cameras and witnessing supernatural phenomena isn’t even a Five Nights at Freddy’s original. The hilariously cheesy FMV (full-motion video) surveillance game Night Trap predates Five Nights at Freddy’s by over 20 years. Instead of a night watchman like in FNAF, you are part of a police squad with access to a mansion’s surveillance cameras. You then trigger traps to protect the scantily clad teenage girls within from a gang of vampires. In essence, you’re a glorified security system.

While you may not find the game very scary with your judgemental modern eyes, the United States Senate certainly did. Night Trap played a role in the ESRB’s creation just as much as Mortal Kombat did. Look it up, it’s true.

The mundanity of these tasks was likely not intentional but more of a side effect of most horror games’ lack of focus on combat. Without the ability to shred through foes like Doom, developers had to think of other ways to keep the player occupied to prevent the game from becoming a walking simulator.

So, if chores are a part of horror gaming’s DNA, why bother with the maintenance horror label? Because it isn’t just about the presence of chores. The beauty of maintenance horror lies in how it weaves those tedious elements directly into the game’s story.

The Everyman Aspect

In Five Nights At Freddy’s, you aren’t a suave badass gunning down zombies like Leon S. Kennedy or a tormented husband like James Sunderland going through their personal hell. You are Mike Schmidt, a night watchman with no special skills other than looking through cameras quickly. Despite the horrific setting, Five Nights At Freddy’s immediately communicates the tedium of the job.

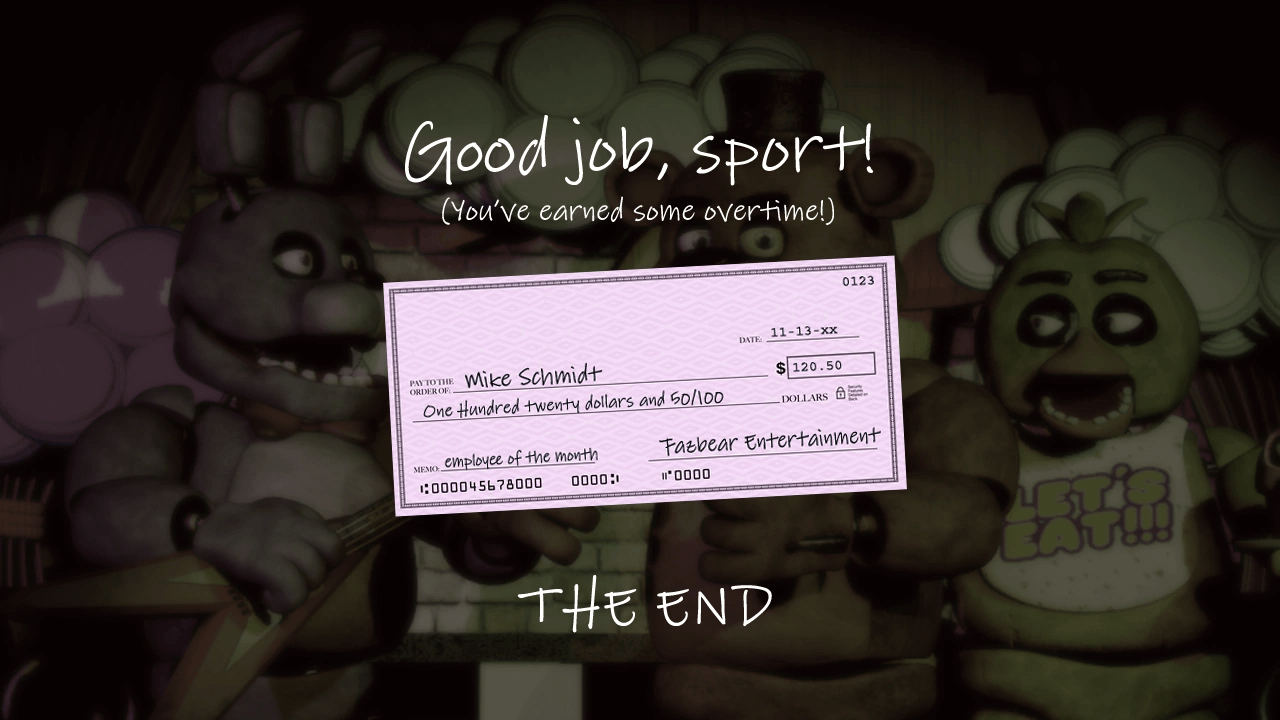

Phone Guy’s tone doesn’t sound fearful or even worried while teaching you the basics. To him, you’re just the latest in a long line of security guards who worked at this abandoned pizzeria. Beating the game doesn’t even reveal answers to the game’s mystery. You get a hilariously low $120.50 for your troubles, barely minimum wage for 1993.

Puppet Combo’s Night Shift and Chilla’s Art’s The Closing Shift are about retail employees who find themselves stalked for the crime of doing their jobs. These games instill fear despite the bright city lights and a constant stream of customers. If anything, the presence of both makes you more uneasy, waiting for the other shoe to drop.

Mike Klubnika’s Unsorted Horror puts you through various mundane jobs in dystopian post-apocalyptic settings. My favorite part of the collection, The Other Side, is that you operate a finicky drill and secretly dig a tunnel into the outside world before the corrupt authorities stop you. There are no tutorials to hold your hand here, and there’s no guarantee that the “other side” is even worth it. All you can do is dig.

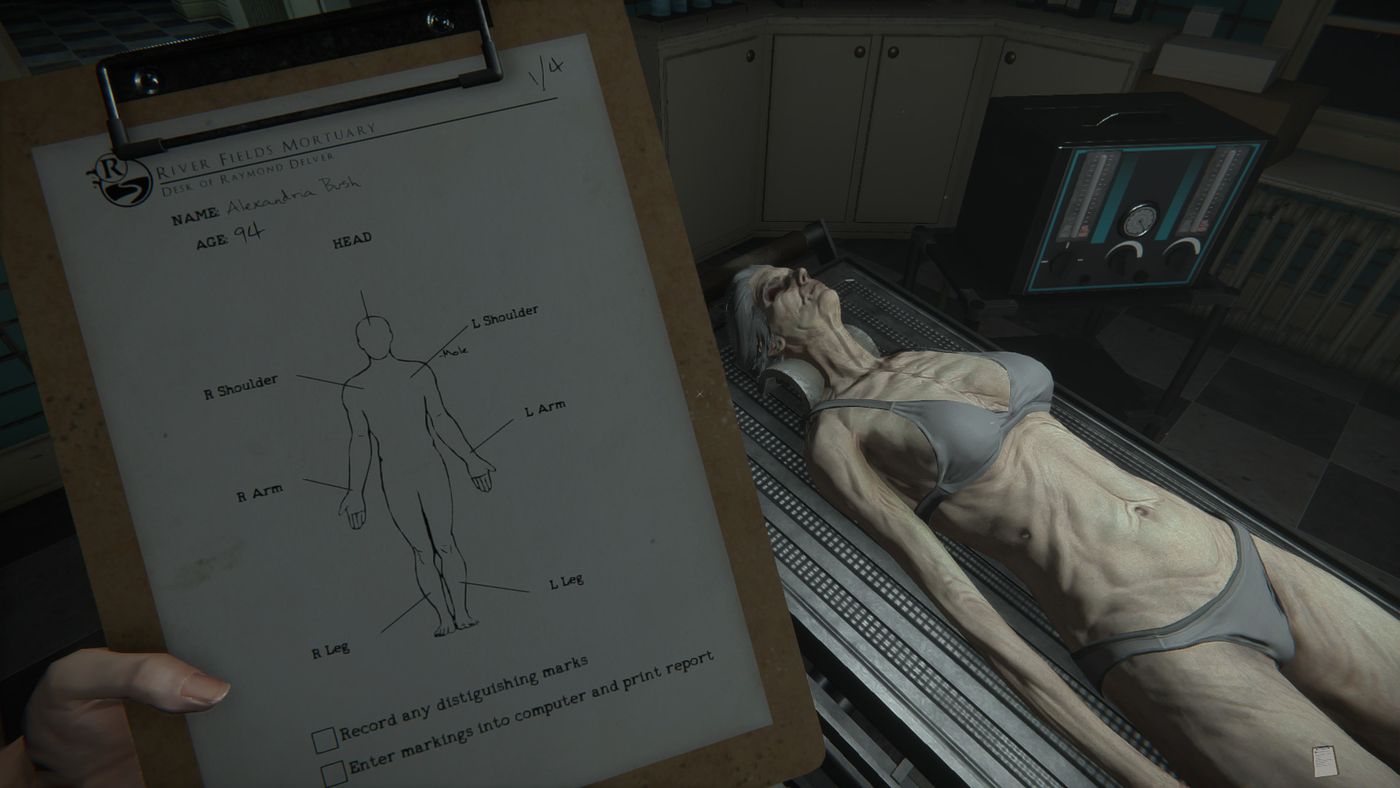

I could keep naming more games. The Mortuary Assistant’s clinical deconstruction of the human body. Phasmophobia’s scientific treatment of the supernatural. Cleaning up the aftermath of sci-fi horror scenarios in Viscera Cleanup Detail. The expendable expeditions of Lethal Company. Iron Lung’s claustrophobic “field research” on a doomed submarine. The pointless extermination of “pests” in Perfect Vermin.

But let’s go back to the title.

Why are “boring” jobs so popular in horror games?

At the risk of sounding pretentious, I believe humanity secretly loves “boring” because it symbolizes stability. The routine cycle of tedious tasks means everything is working as intended. We may want to take a break from the cycle now and again, but routines are a safety net that we all lowkey appreciate.

Horror games destroy that cycle. Strange forces start to invade your life, and you can barely comprehend them, let alone survive. These “boring” jobs challenge the player to survive their very own horror movies. There’s a deceptive ease to the mechanics that suddenly become complex when an axe-murderer bursts through the doorway.

When you look at the wrong security camera, forget to stock the shelves, or drop a screwdriver, a bit of self-hatred seeps through. These are simple tasks, and you can’t do them to save your life. You are not special. You’re just human.

At the same time, that’s what makes it so relatable. You’re just you. That alone makes your survival instinct stronger than if you were some invincible action hero like boulder-puncher Chris Redfield. The underlying sense of “smallness” from mundanity makes the horror feel even more overwhelming.

In horror, vulnerability is everything. Without that sense of danger, the feeling that at any moment, your character separates from the mortal coil, horror games simply won’t work. Just look at the words “survival horror.” That’s not exclusive to video games. From the earliest humans hiding from sabretooth tigers to our modern-day fears of serial killers, it’s always been clear.

Surviving is horror.

Categorized:Editorials