Blessed are the Bold: ‘Immaculate’ Challenges the Virtue of Feminine Meekness [Fatal Femmes]

Few characters in horror embody contrast like the pregnant nun. After committing to a life of chastity and spiritual marriage to God, she somehow finds herself “in the family way” with a bulging belly and a pending arrival. She is a symbol of subversion and corruption made flesh, a visible sign of hypocrisy from an institution rife with controversy. By centering the woman inside the habit, Michael Mohan’s Immaculate uses the image of a pregnant nun to explore questions of bodily autonomy and reproductive freedom.

Rather than a totem, Cecilia (Sydney Sweeney) is a relatable woman who finds pregnancy thrust upon her and must fight to be seen as fully human. She may be a virgin, but she is not the serene Virgin Mary, perpetually portrayed as a symbol of silent sacrifice. In fact, Immaculate asks us to question this centuries-old characterization. Watching Cecilia rage at the injustice invading her body challenges us to reconsider our understanding of Mary’s experience and question the virtue of meekness itself.

Who Exactly Is Sister Cecilia?

Cecilia is an American novitiate who moves to an ornate but isolated convent in the Italian countryside. Shortly after taking her vows, she finds herself mysteriously pregnant. As a steadfast virgin, Cecilia has no idea how this could have happened. But Cardinal Merola (Giorgio Colangeli) proclaims it a miracle and decides she’s carrying the second coming of Jesus Christ. Though she never vocally responds, the young nun seems to have misgivings. She stands in an ornate gown and veil at the altar, crying silent tears as the congregation literally sings her praises. She has become a living embodiment of the Virgin Mary, expected to do nothing but exist as her body grows a miraculous child. Father Tedeschi (Álvaro Morte) convinces the frightened mother-to-be that this has been God’s purpose for her life all along. But Cecilia realizes that her exceptional condition is a curse rather than a blessing.

Upon her pregnancy, Cecilia becomes simultaneously precious and disposable—valued only for the cells growing in her womb. Her fellow sisters treat her with extreme reverence or bitter jealousy and one young nun tries to drown her in a bathing pool. To Cecilia’s relief, help arrives in time, but she’s stunned to find that her life is not a priority. Dr. Gallo (Giampiero Judica) barely looks at her when delivering the good news that the baby is unharmed. She insists that the fetus may be ok, but she is not and demands a second opinion from an outside obstetrician. Denied this reasonable request, Cecilia fakes a miscarriage and convinces Father Tedeschi and another priest to rush her to a hospital. But her ruse is discovered en route and they literally drag her, kicking and screaming, back to the abbey.

The Truth About Her Pregnancy

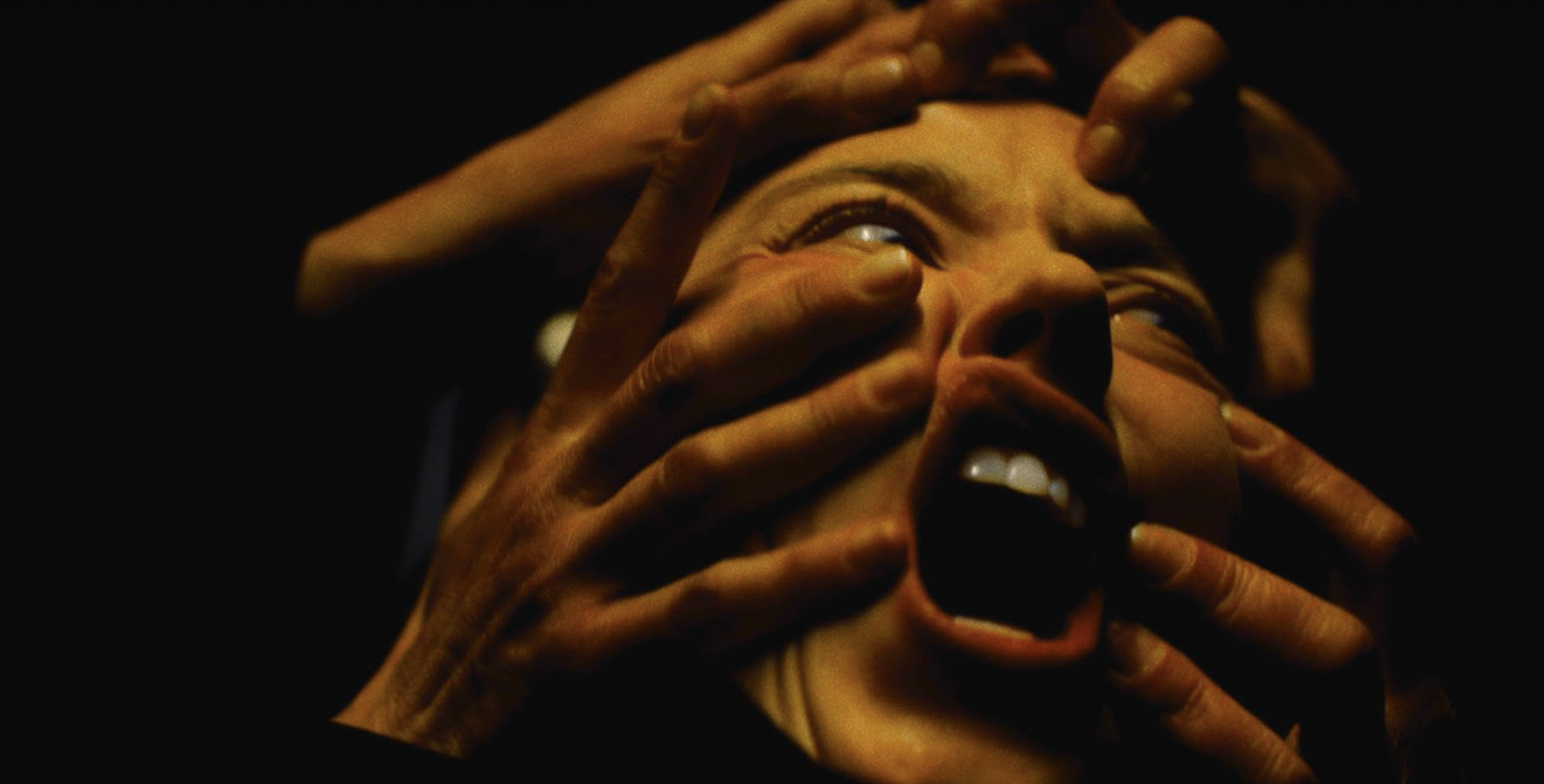

Only then does Cecilia learn the truth of her condition. Rather than an immaculate conception, she has been implanted with a concoction of DNA taken from a holy relic. Using a nail said to have pierced Jesus’s flesh on the cross, Tedeschi extracted genetic material and used it to create a fetus. He’s groomed her to be a fertile womb and a pawn in this devious plan. Cecilia becomes a prisoner both in the building and in her own body. With crosses burned into the souls of her feet, she bangs on a locked door screaming for release.

As we listen to her wails of rage and terror, Mohan lingers on a statue of the Virgin Mary and implies that the screams are coming from the saint herself. This striking comparison reminds us that Jesus’s mother was once a young woman surprised to find herself pregnant with a child she never asked for. Did Mary share Cecilia’s horror at the life-changing experience foisted upon her without consent?

An Immaculate Motive

It’s difficult to say exactly what pushes Cecilia over the edge. She lies in a hospital bed as Dr. Gallo and Mother Superior (Dora Romano) once again examine her body. They discuss her care with each other in a language she doesn’t understand and offer her little more than empty compliments and scripture.

Mother Superior repeats Matthew 5:5, “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.” and it seems Cecilia has resigned herself to this fate. She doesn’t even bother to resist anymore. She knows she is trapped and likely to be killed as soon as her body is no longer useful to the baby. But as the old nurse turns away to gaze in awe at the ultrasound screen, something in Cecilia snaps. Perhaps she’s finally decided that a world in which the meek are punished with oppression and medical enslavement is not one she wants to inherit.

Along with this scripture, the nuns have been bombarding Cecilia with reminders that suffering is an act of love. Of course, this quip almost always comes from the person not actually doing the suffering but watching from afar and benefiting from someone else’s pain. Cecilia may have willingly become a “bride of Christ,” but she never agreed to give up control of her body. She now knows this conception is not a miracle and that she is a guinea pig for a scientific hobbyist rather than a chosen vessel for the Holy Spirit. While hearing her coerced “confession” Cardinal Merola asks her why God is not stopping them if their actions are sinful. Cecilia ponders this query and seems to answer it by enacting another religious assertion: “The Lord helps those who help themselves.” She rejects meekness and boldly attacks anyone who blocks her path to liberation.

Getting Revenge And Catharsis in Immaculate

As Dr. Gallo retrieves her medicine, Mother Superior offers Cecilia yet another empty compliment then turns to gaze lovingly at the ultrasound monitor. Cecilia takes this opportunity to grab a metal cross and bash in her head. The old woman offers little resistance, staring in horror at the rebellious mother-to-be. Unfortunately, Cecilia is not content to merely subdue. Standing over her former caregiver, she delivers blow after blow, unleashing 40 weeks’ worth of rage.

While cathartic, her actions mirror the pain she’s been forced to endure. Pregnancy is more than a single instance of conception bookended by birth; it is nine months of continuous growth. Cecilia has been pregnant for every minute of the past 280 days and her body will never again be the same. Each blow represents a fraction of the time she’s spent locked in the prison of this physical experience. She prolongs her attack just as Mother Superior has prolonged the violation against her.

Next Cecilia wanders out to the corridor where she meets the man who administered her vows. Cardinal Merola cowers in fear as Cecilia attacks with a rosary. Used to mark repeated prayers for penance, Morelo has used this spiritual tool to control the actions of the nuns in his convent. Fed up with his lies, Cecilia rejects his path to forgiveness and turns the tables on her oppressor. Her chosen weapon becomes a symbol of his hypocrisy. The Cardinal has abused his power and failed to protect his flock. She now uses the rosary not to count off an endless series of prayers she no longer believes in, but to stop the words of the man who has led them all astray.

Unholy Penetration

Her final weapon is not only the most symbolic, but also the most satisfying. After burning Father Tedeschi in his lab, Cecilia retreats into the subterranean catacombs and searches for a path to salvation. After stumbling upon the body of her friend—another victim of this murderous cult—Cecilia spots daylight at the end of an earthen tunnel. She’s crawling to freedom when Father Tedeschi drags her back inside. He begins to slice her stomach and prepares to rip out the baby then kill the mother. Fortunately, Cecilia is not without defense. She finds in his pocket, the holy nail used to extract the offending DNA. Cecilia stabs Father Tedeschi in the neck, penetrating him with the very phallic object that impregnated her to begin with. Blood from the wound covers Cecilia, a visible symbol of the violent sexual act he forced upon her.

Cecilia may be a murderer, but she is simply trying to save herself. She knows she will be killed after the birth and that the clergy will continue on with their corrupt plan. What if Cecilia’s baby proves to be a disappointing savior? How long will it be before they desire a second child of God? Mother Superior, Cardinal Merola, and Father Tedeschi are all symbols of a church that has betrayed the “meek” followers it claimed to protect. They are not innocent faith leaders but murderous villains willing to do anything in the name of their perverse understanding of God.

Burn It All Down

It’s no coincidence that this abbey was built atop the tomb of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr. Father Tedeschi and Cardinal Merola expect Cecilia to become a martyr as well. They have no qualms about using her body at the risk of her life because they assume she would willingly offer it up in accordance with their whims. But martyrdom without choice is nothing more than murder. St. Stephen gave his life for his own beliefs while Cecilia has been robbed of the freedom to live out her faith.

Not content to just kill the offenders, Cecilia knows she must take down the whole system. As long as the relic remains, another Father will come along and try to victimize more women. She also knows that it’s not enough to simply escape. There are many other nuns eager to take her place. Whether enablers or future victims themselves, there will always be women willing to secure their own salvation by continuing patriarchal oppression. They’ll tell themselves they are following their faith. But really, they’re abdicating personal choice and hiding behind blind belief to protect their own position of relative safety.

Monstrous Birth in Immaculate

The shocking conclusion in Immaculate gives Cecilia one more victim. After escaping Father Tedeschi’s grasp, she emerges from the catacombs in active labor. We watch minutes of painful contractions before hearing the birth and witnessing Cecilia’s horrified reaction. We never see the product of her womb, but unsettling coughs and gasps hint at an inhuman monster. Cecilia severs the umbilical cord with her teeth and smashes the infant with a rock. It is the fruit of the poisoned tree and must be destroyed. Mohan ends the film on this shocking moment, forcing us to grapple with the extremity of Cecilia’s rage.

Though harrowing to watch Cecilia carry a child against her will, Immaculate reflects a painful reality playing out across the United States. With the fall of Roe v. Wade, millions of people lost control over their own bodies. Women like Cecilia – survivors of rape – are now being forced into the body-altering, life-changing act of gestation in the name of someone else’s religious beliefs. Others are denied care after suffering devastating complications with wanted pregnancies. They must either travel hundreds of miles at great personal expense or wait until they are at death’s door before being deemed worthy of routine procedures. And women who simply choose not to become mothers are denied the ability to make that choice for themselves.

The Sad Reality of Immaculate

These laws exist because our patriarchal society places women in the role of uncomplaining caregiver. We are expected to want nothing more than to bear healthy babies and surrender our lives to create the next generation. We can trace this expectation back to the Virgin Mary. Her silent abdication is honored as the ideal of feminine devotion, her meekness prized above all other womanly traits. We’re told we should all strive to be like Mary and sacrifice our bodies and lives on the altar of evangelism. Any deviation from her example is considered not only a sin, but also a betrayal of our duties as a woman.

With Immaculate, Mohan creates a unique glimpse into Mary’s world. Perhaps this legendary saint once felt much like Cecilia – violated, frightened, and betrayed. If we can begin to see Mary as a human being rather than a symbol of maternal martyrdom, maybe we can find the path toward empathy and bodily autonomy for all of her sisters.

Categorized: Editorials Fatal Femmes