Dario Argento’s ‘Phenomena’ Inspired This Iconic Video Game

It’s no secret that video games have been borrowing from movies for decades. Be it Hideo Kojima lifting elements from Escape From New York for his Metal Gear Solid series or the xenomorphs inexplicably showing up in Contra, gaming has only become more cinematic over time. These days, the opposite is also true, with films like John Wick 4 having no qualms over referencing the top-down thrills of games like Hotline Miami, and that’s not even mentioning how Hollywood is finally taking video game adaptations seriously.

However, this creative give and take isn’t always relegated to mere homages and borrowed aesthetics. Sometimes, the decision to incorporate elements from a film into a video game has a lot more to do with developers wanting to add their own spin on an idea that resonated with them personally, with the ensuing work of interactive art actually commenting on its source material.

I believe that this is precisely the case with Hifumi Kono’s Clock Tower and the film that inspired it, Dario Argento’s underrated Giallo thriller Phenomena. With WayForward reviving this survival horror classic for a new generation with a definitive remaster in the form of Clock Tower: Rewind, now is the perfect time to look back on how Argento’s filmmaking ended up informing the basis of modern interactive horror.

For the sake of clarity, I think it’s best if we begin this discussion in chronological order by diving into the production of 1985’s Phenomena and the years leading up to what many consider to be the first proper survival horror experience.

Inspired by a true crime radio presentation about how a French murder case had been solved by studying the insects living on a corpse, Argento proceeded to write a bizarre screenplay about the fictional daughter of Al Pacino using insects to solve a murder mystery in an alternate universe where the Nazis had triumphed after World War II. Obviously, this deeply odd premise had to be revised in order to secure the funding necessary for the film’s proposed effects sequences involving arthropods—though Argento still insists that Phenomena takes place in an alternate reality.

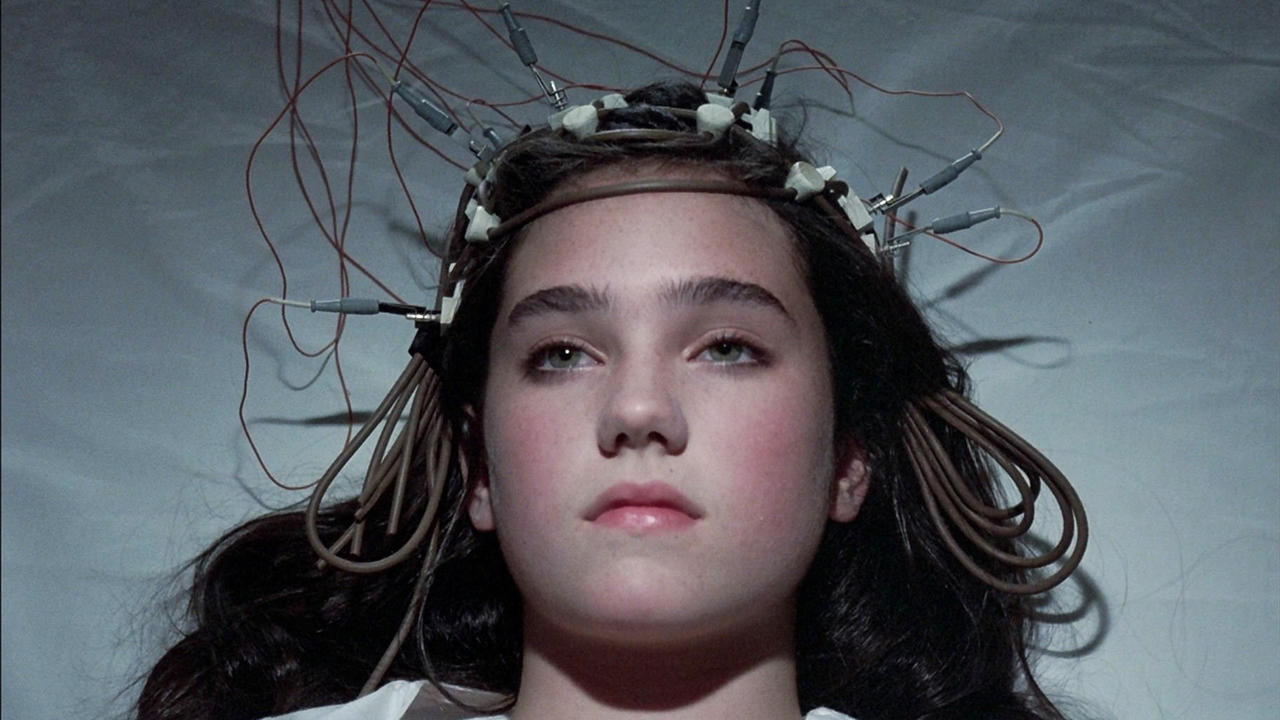

Once again assembling an international cast and crew (a hallmark of Argento’s multilingual productions), the director began filming on location in Switzerland in 1984, with a then 14-year-old Jennifer Connelly speaking English while the rest of the mostly European performers spoke in their native tongues.

In the finished film, Argento once again tells the story of an American outsider coming to live in an isolated all-female academy in Europe and uncovering a deadly secret. Unlike Suzy in Suspiria, however, Phenomena’s Jennifer Corvino (Connolly) isn’t alone in her battle against a mysterious serial killer, with our main character allying herself with an eccentric entomologist (Donald Pleasance) and his pet Chimpanzee Inga, as well as a legion of insects that see Jennifer as their commanding “queen”.

Unfortunately, Argento’s symbolistic script and surreal aesthetics were already considered a relic of the technicolor past when the film was released in January of 1985, with a botched international release (which retitled the film to Creepers and removed over a half-hour of footage) also contributing to Phenomena’s lackluster reception. Thankfully, the movie’s idiosyncratic style meant it gained a second life among audiences that were more accustomed to weird cinema that focused on ambiance rather than logical narratives.

That’s how Phenomena reached a young Japanese videogame developer named Hifumi Kono. During the early 90s, Kono was working for a small studio named Human Entertainment, with the developer expressing interest in creating the world’s first cinematic horror game that would also pay homage to his favorite film director, Dario Argento.

An experimental endeavor made by a small team, the project that would later become known as Clock Tower was a risky move for Human, with the low budget and lack of combat convincing several employees that they were working on a future flop. Nevertheless, Kono insisted on simulating a three-dimensional space with cheap 2D graphics while also digitizing photographs instead of drawing sprites by hand in order to make everything feel more cinematic. While Clock Tower’s Jennifer Simpson was clearly modeled after Jennifer Connelly’s character in Phenomena, a female staff member ended up acting as the basis for Clock Tower’s Jennifer Simpson. Animators rotoscoped her expressions and movements much like the developers of Broderbund’s Prince of Persia had done half a decade earlier.

There had actually been quite a few attempts at cinematic horror gaming before Clock Tower, with titles like Splatterhouse and 1989’s Sweet Home (a licensed title that would later inspire Resident Evil) attempting to gamify scary stories by adding a spooky coat of paint to traditional gaming tropes. However, Kono wasn’t content with simply borrowing the aesthetics of genre cinema and applying them to gaming. He wanted to make a proper interactive movie that took full advantage of player choice in much the same way that cinematic titles like Heavy Rain and Until Dawn would do decades later.

Phenomena was chosen as a jumping-off point simply because Kono liked the film and believed it featured a protagonist with more agency than your average final girl. Jennifer Corvino didn’t just run and hide (though that would be an important part of the gameplay loop for her digital counterpart). She also explored creepy locations and put herself in danger simply because it was the right thing to do. This is likely why Clock Tower presents you with the opportunity to reluctantly escape from the mansion in a vehicle early on, with Jennifer Simpson exclaiming that she doesn’t want to abandon her friends.

While the game also borrows ideas from films like Tony Maylam’s The Burning, with the flick’s urban-legend-inspired iconography partially inspiring Scissorman, the fact is that, despite what critics frequently claim, Clock Tower was never meant to be a slasher. Your relentless stalker is really meant to be a mechanical source of tension, not the focus of the story. The title’s similarities to Phenomena suggest that Kono was aiming for an interactive Giallo film about parenthood and occultism boosted by a healthy dose of nightmarish imagery.

And speaking of similarities, there are quite a few here. Aside from Jennifer herself and the overall premise of a group of youngsters being sent to live in an isolated mansion where they’re systematically murdered by a mysterious killer (who is eventually revealed to be the deformed offspring of the woman who originally brought our protagonist to her new home), there’s a recurring theme about contrasting different kinds of parenthood as well as a familiar Giallo aesthetic. Clock Tower’s iconic theme also sounds like a bit-crushed Goblin song track, though it’s a shame that the title doesn’t feature any licensed heavy metal music like Phenomena’s use of Motorhead and Iron Maiden.

Funnily enough, much like the case of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Leone’s pseudo-remake For a Fistful of Dollars, it’s the ideas that didn’t survive the translation that tell us what Kono and his team really thought about Argento’s work. For instance, the depiction of one of the Barrows twins as a Lovecraftian abomination inhabiting the catacombs beneath the manor shows us that the developer is much more interested in the esoteric side of Argento’s filmography. In fact, the “supernatural demon child” angle would arguably have improved Phenomena, with the film’s problematic depiction of disabilities being so controversial that it even factored into Daria Nicolodi’s divorce from Argento.

It’s also interesting that Jennifer’s arthropod-related superpowers were removed from the game (though there are still a few nods to it during a couple of insectoid scares). But, it can be argued that Kono traded this ability in for a much more powerful one: the ability to be aided by an all-seeing player.

Countless more comparisons can be made between these projects, such as how the added interactivity allows for clever “what-if?” moments akin to Argento’s infamous dream sequences. But to me, the most interesting connection is how these stories exemplify the creative spark that can occur when an artist from a different culture attempts to breathe new life into a familiar tale. That’s why both the film and the game can co-exist as completely different recipes assembled from the same ingredients.

So next time you boot up the opening chapter to one of the most influential survival horror experiences of all time (hopefully with the added rewind mechanic from WayForward’s remaster), I’d recommend taking a moment to appreciate how an infamous cinematic flop managed to inspire a gaming classic.

Categorized: Editorials