How One Performance Transforms ‘Christmas Evil’ Into The Scariest Killer Santa Movie Ever Made

So much of Christmas horror cinema is about high contrast, juxtaposing bright lights, pretty trees, and bright red Santa suits with slaughter, suffering, and existential terror. It’s a time of not just beautiful sights, but often socially enforced, ritualistic joy, so when something intrudes on that, ax in hand, it’s both frightening and, in an odd way, refreshing. In Christmas Evil, it all begins with Brandon Maggart‘s eyes.

In the role of a disturbed working-class man who slowly morphs into his own vision of Santa Claus, Maggart is the raw, pure, heartbreaking core of what might have been an otherwise bland film. Through a mixture of empathy and unexpected savagery, he delivers the single best performance in any “Killer Santa” horror film and transforms Christmas Evil into an essential holiday horror picture.

Lewis Jackson’s 1980 slasher film, originally released as You Better Watch Out, has been overshadowed over the years by its more successful and notorious Christmas horror predecessors (Black Christmas) and successors (Silent Night, Deadly Night), including other killer Santa films. It is, at best, a Christmas horror film nestled in the second tier of the subgenre, behind bigger names viewers are more likely to reach for first. Revisiting the film a decade after I first saw it during an earlier search for lesser-known Christmas horror, it’s easy to see why. Christmas Evil is slower than other Christmas horror films, more patient, and more dialed into psychological subtleties and quirks, making it less flashy and less campy than its better-known peers.

Maggart plays Harry Stadling, a middle-aged man obsessed with Santa Claus. Why? Because when he was a boy, he literally saw Mommy kissing Santa Claus. Well, more precisely, he saw Santa Claus fondling Mommy. While that moment might have served to clue another kid into the fact that Santa was just his Dad in a red suit, for Harry it did something else entirely. It shattered his perceptions of Santa, sex, and Christmas, causing his life to spin off on a much stranger trajectory.

As an adult, Harry goes to increasingly extreme lengths to craft his own version of the idealized, reverent Santa he lost in his childhood. He crouches on rooftops with binoculars in his neighborhood, peering into windows to see if the local kids are being “good” or “bad”. He even works as a supervisor at a toy factory. There, he chides his coworkers, annoyed that they seem to care more about money and nights out at the bar than about crafting pure, quality toys for children. Desperate to be the change he wishes to see in the Christmas world, Harry’s also been crafting a Santa suit of his very own, painting his van up like a sleigh, and preparing for Christmas Eve. Then he’ll finally get to prove how the holiday should really work.

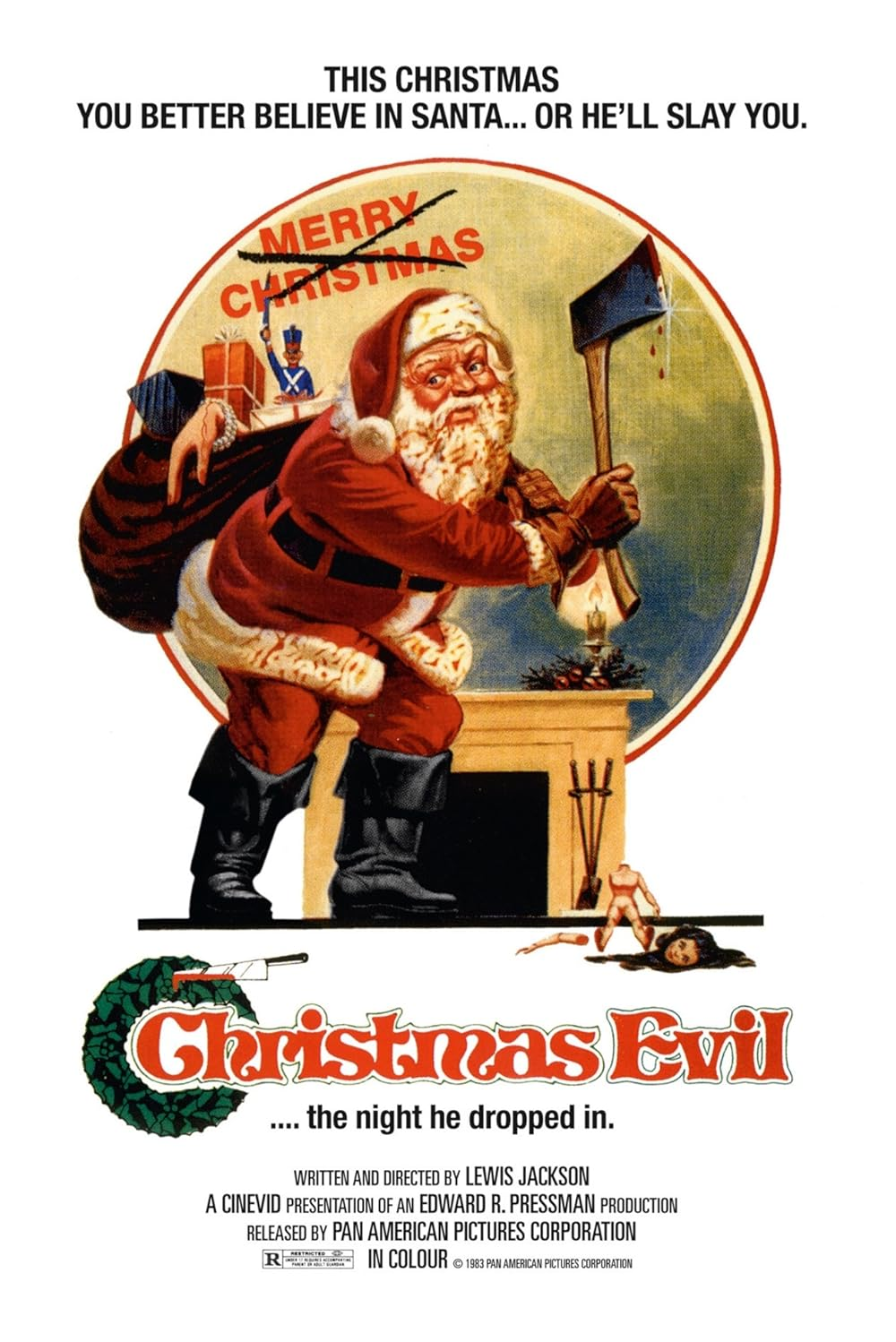

A movie featuring an ax-wielding Santa Claus on the poster certainly telegraphs where this is eventually going. But to the film’s credit, Christmas Evil is a movie that’s always after something more. Jackson’s script sets up Harry not as a man simply determined to punish the “bad” people, but as a man who truly wants to make a better world for kids than the one he had. The problem, of course, is that he’s clearly suffering from mental illness and decides to isolate rather than reach out for help.

So when Harry prepares for Christmas Eve by literally gluing a white beard to his face, all the forces that have served to build this well-meaning but doomed holiday bubble around his life come together in a flash of inspiration. He starts to feel more and more like he’s the genuine article, the real Santa Claus, capable of inspiring joy and heartbreak with a single carefully wrapped package.

That balance between joy and heartbreak is crucial to the film, which means that from the moment he first appears onscreen, waking up in Santa pajamas, Maggart has to absolutely nail playing Harry as a guy who truly thinks that he’s not just doing the right thing, but the magical thing. He’s spent more than 30 years of his life studying Santa Claus, the benevolent gift-giver who also punishes bad behavior, corruption, and indifference. This means that, when he’s around well-behaved children, he’s truly happy, reveling in the innocence he himself lost, desperate to make sure they all have a good Christmas. But when he’s around the adults who misunderstand, bully, and disregard him, or when he sees a naughty child, Harry’s face shifts immediately, becoming the darker Santa who doles out bad gifts and vengeance.

Maggart’s performance has to contain not just both of these elements, but both of them at the same time. His face, etched with pure ’70s character actor grit, has to evoke these ideas in every scene, whether he’s shuffling around the toy factory or rehearsing his Santa act in his house, and his eyes have to convey that he’s both wearied by the state of the world and itching to do something about it. For the first half of the film, it all simmers in those eyes, as Harry makes moves and quietly plans his ultimate Christmas Eve, and it boils over in the aforementioned beard-gluing scene.

That scene, one of the most disturbing character moments in all of ’80s horror, allows Maggart to let every emotion out at once. It all comes through his eyes as he tugs that beard, realizing it’s truly part of him now, that he’s actually made his dream a reality. There’s unbridled glee in those eyes, but there’s resolve, too, and beneath that, a sense of savagery, a sense that he’s unstoppable. Though it is a slasher film with a killer hook, no one dies in Christmas Evil until nearly an hour into the 94-minute runtime, which means we simply have to take Harry’s word that something dark and exciting is coming. Because of Maggart, we can not only trust in the film but get lost in it, just as Harry gets lost in his Christmas mission.

But most disturbing of all is what happens after Harry has transformed. With a beard and a beautifully made red suit, in a van packed with toys, he heads out into the night to not just play Santa, but fully embody him. And it goes very well at first! He drops off a vanload of toys at a children’s hospital, gives a naughty kid a bag of dirt, and carries on laser-focused on his task. By the time it becomes clear that his task also includes violent reprisals for his awful coworkers, we’re already well into his night ride, and fully invested in Harry’s journey.

We’re also hanging on to the conceit established by Jackson’s script. We know by now that Harry is delusional and lost in the reverie of his Santa transformation. That means the more melodramatic touches that emerge later in Christmas Evil—adults being transparently cruel to Santa, children being unabashedly loyal to him—might just be part of Harry’s grand fantasy. It’s hard to blame him for murdering adults who behave like cartoon villains in cold blood, just like it’s hard not to cheer him for giving toys to needy kids.

It’s here that the real psychological crux of the movie is made clear. Harry didn’t grow to hate the very idea of Santa after his childhood encounter with a fake Kris Kringle, nor did he grow to hate Christmas. Instead, he spent decades not just idealizing a better version of the holiday and its gift-giver, but planning for the day that he could become that better version. His entire life has been a rehearsal for the ultimate method-acting performance, a chance to heal psychic wounds that no one else even bothered to address. It’s not just a descent into madness, but an American tragedy made flesh, and Maggart has to embody all of that while also participating in a weird little movie about a killer Santa Claus.

Saddled with that task, his eyes become infinite pools of sorrow and potential, his face a road map of hard work and even harder emotional truths. It’s a performance so nuanced, so impish, so tinged with regret and fear and doubt, that it’s hard not to root for the guy even as he turns darker. Maggart’s work here transforms Christmas Evil into a vastly rewarding psychological journey through the dark side of the holiday, a side where everyone feels pressured to become the best version of themselves. That all begins and ends with Brandon Maggart, and 44 years later, we still can’t look away.

Categorized:Editorials