Into Developer Minds: An Interview With Quinn K. of An Outcry

In any art form, so much innovation and creativity are found in indie spaces. Though a lot of mainstream titles have much to offer, the realm of indie works has a greater means of self-expression; there are no limits, there are no rules, just the freedom in creating what one wants to create.

It is through this column, Into Developer Minds, that I want to shine a light on indie developers in gaming. To not only highlight their works and what they have to offer but even to hopefully inspire those looking to get into game development. In each interview, I will be featuring a different game developer, asking them a little about their background and then more specifics regarding their recent project(s).

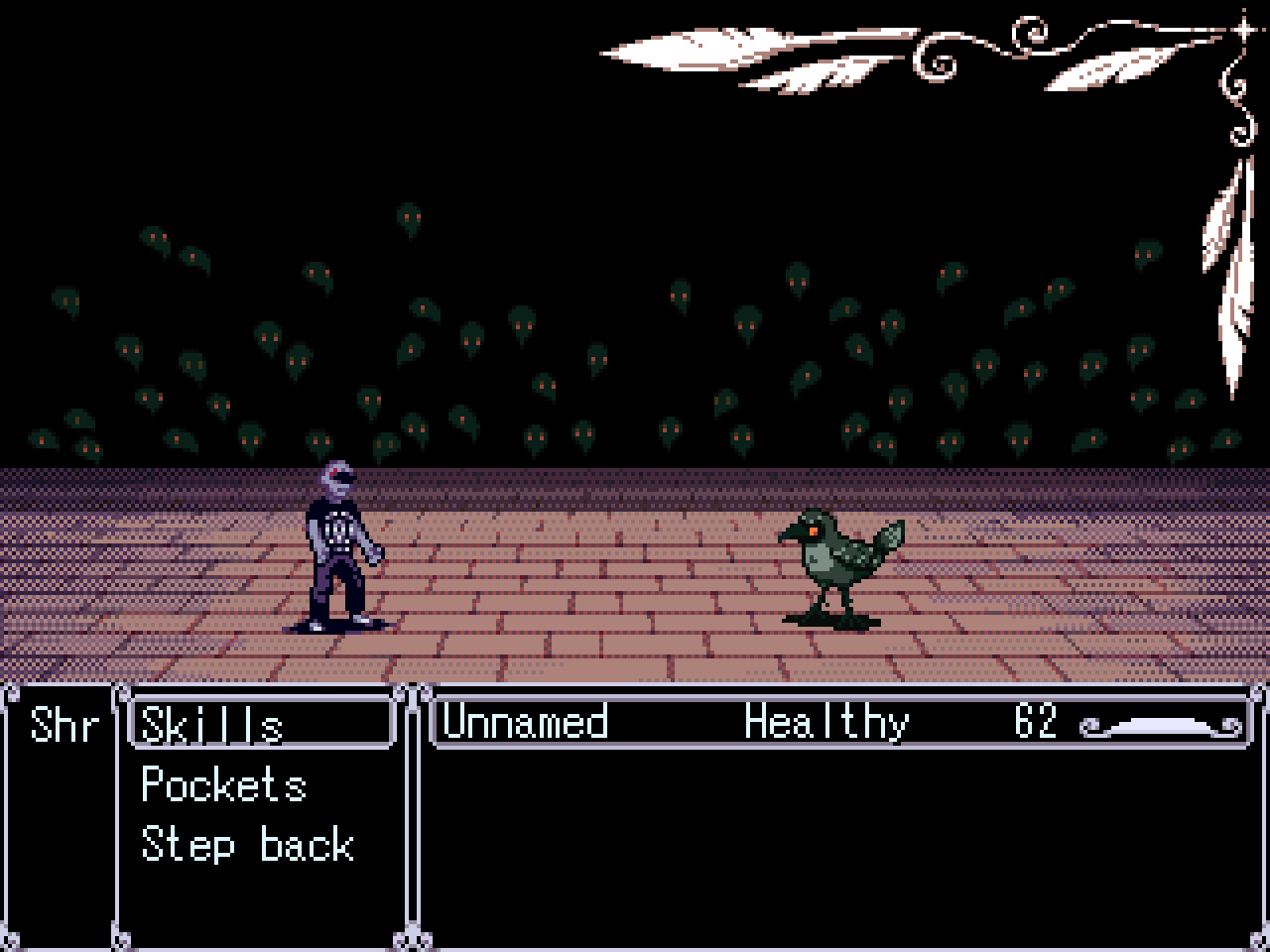

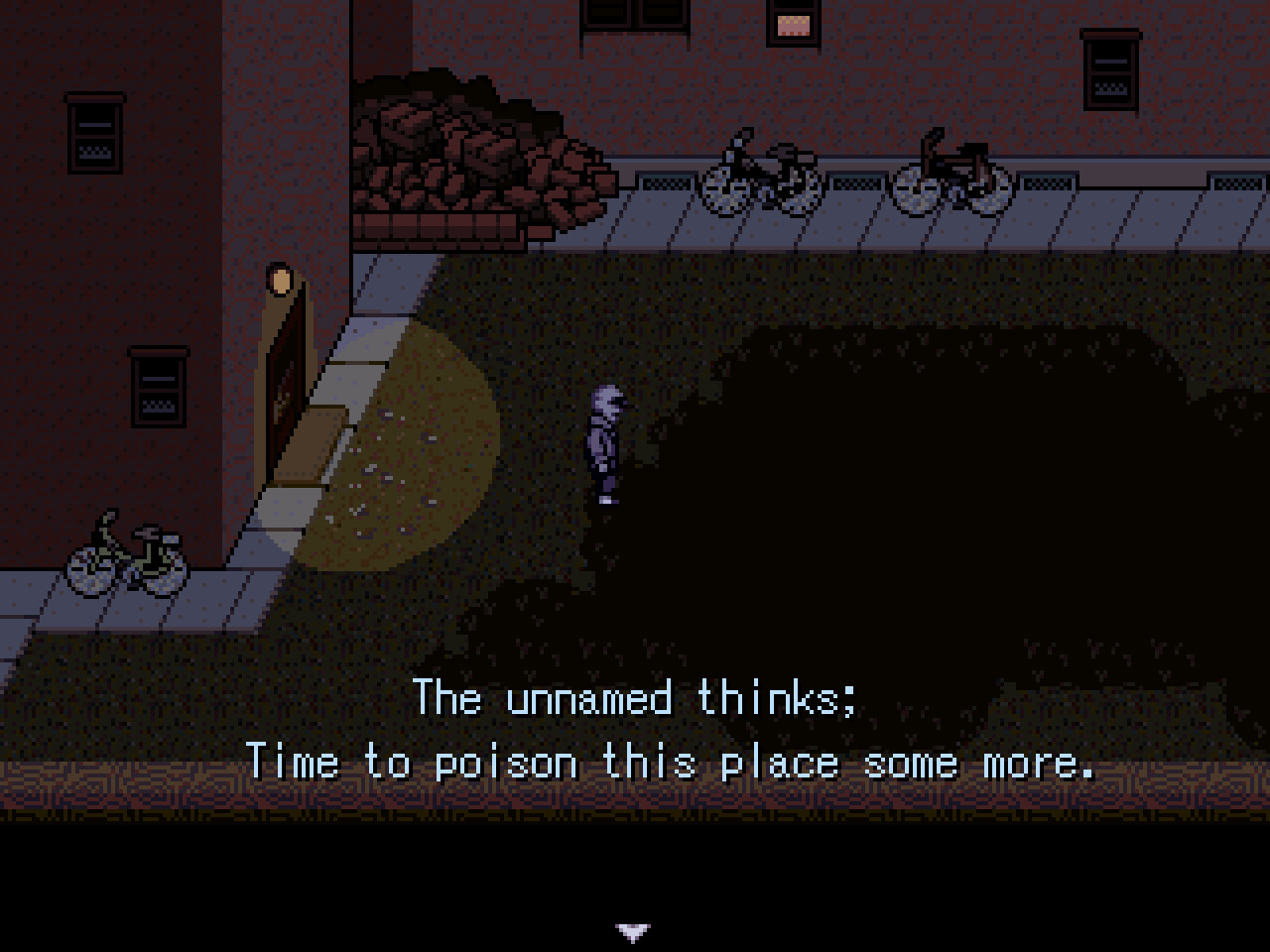

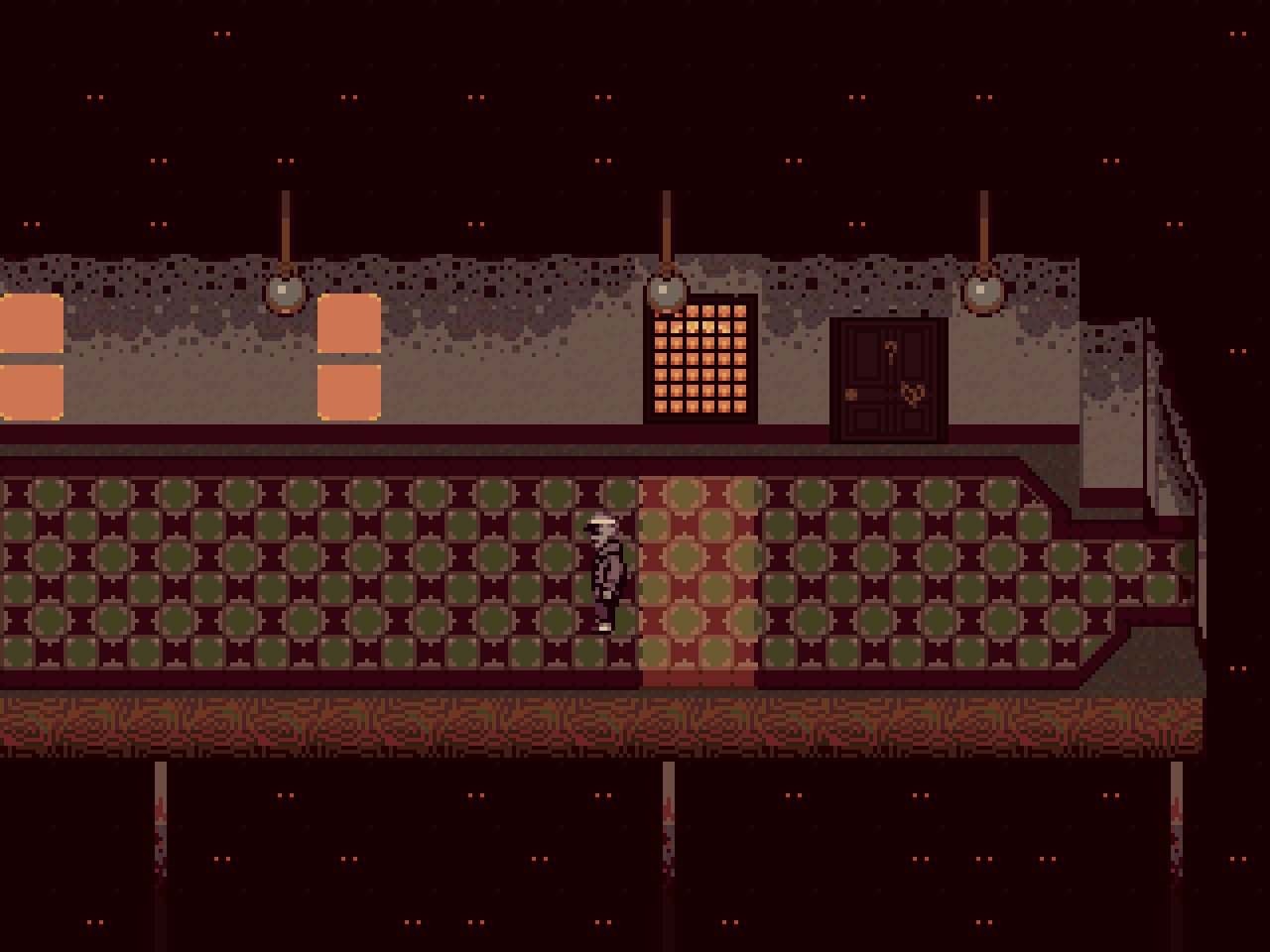

For this first installment, I spoke to Quinn K. about their game An Outcry. This psychological horror, built out of RPG Maker, involves a haunting narrative with a political angle. Through the mechanics and narrative, Quinn has designed a world made to exude gloom and chills, the world’s grim tone creeping through each interaction and environmental design. An Outcry is an intriguing work of horror, and it was a pleasure being able to write to Quinn and learn more about their experience and process.

Michael Pementel: Where did your journey with gaming begin? What were some of your favorite games growing up (for fun and those that would go on to inspire you)?

Quinn K: My first games were on the original Game Boy my father had – Pokémon Blue comes to mind, as well as his copy of classic Asteroids. Eventually, I’d go on to own a Game Boy Advance SP and a GameCube, and I feel it’s those two consoles that had the biggest early-life impact on me, with titles like Yoshi’s Island (the GBA port), Mario and Luigi: Superstar Saga and, on the GC, Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door. I would also dabble in emulation and play games like Earthbound and Mother 3 in English later, as well as a myriad of free RPG Maker titles (OFF, Space Funeral, Ib, Pen Palz). The latter especially would inspire a lot of my narrative and design sensibilities.

MP: What ended up driving you towards game design?

QK: I’d been an artist for as long as I can remember; I drew a lot, and with the games I played, it came to pass that I would make fan art and, eventually, designs and early playful game concepts based on those old favourites. In 2008, I started making pixel art; since I was a huge fan of the Mother/Earthbound series, my early sprites were predominantly edits and original recreations of that series’ style, which made me start dabbling in fangames. None of them panned out, of course, but the practice was good, and even through active discouragement, I never lost the drive to create in the medium.

MP: What works of horror inspired An Outcry? There is a surreal, psychedelic/psychological essence to this game. What compelled you to explore these areas of horror, as well as the various subjects that make up the game?

QK: OFF, Kentucky Route Zero, and (outside of games) Petscop are big influences of the vibes I wanted and [that also contributed too] An Outcry‘s myriad of visual experiments; however, more directly, inspiration for its story came from beyond our medium: Modernist and postmodernist texts I read (predominantly theatre) proved most informative. Few people know this, but the works of Postdramatic Theatre, like Heiner Müller’s Mauser and The Hamletmachine, or Sarah Kane’s Blasted and 4.48 Psychosis, are drenched in a special, arresting type of horror that An Outcry draws from abundantly. There is a sense of unreality to them, an awareness of their medium, and a sense that the audience isn’t safe. The subjects in An Outcry were largely taken from my own lived experience, but were filtered through the lens of those texts, and given interactivity.

MP: What was emotionally important to you in creating An Outcry? Specifically, what was important for you to convey through the narrative and gameplay, and why? What do you want players to experience when they play your game?

QK: A feeling of downtroddenness [sic] that would compel the player to rebel. The sense that the world doesn’t want the Unnamed [the protagonist] there, but the drive to carry on, to fight in spite. The way constant stress wears on people was important for me to convey, the way it shapes them, and the way they interact with others as a direct result of mistreatment – and that breaking out of that negative feedback loop is possible, and helpful. It’s how the “refusal” mechanic came about: No matter how much the world despises you (through its systems and the people that surround you), you have options, and you can prevail.

MP: As an indie developer, what was your experience like creating the game via RPG Maker? Did you find it user friendly? Would you recommend it and why?

QK: I would not recommend working in RPG Maker 2003, as it is a capricious beast. Its many limitations, quirks, and antiquated UI design decisions (+ lackluster official documentation) make it most useful to somebody who grew up already working in it (as I did with my English translation of OFF). The experience of using it for a commercial product has predominantly been frustrating after the fact, but development itself wasn’t too bad. Still, I would recommend RPG Maker MV over any of the older or newer versions of the engine for use with commercial titles. It’s a great beginner’s engine.

MP: In using RPG Maker, what other challenges did you come across in making the game, and how did you overcome them? Did you find that certain limitations actually guided you towards new ideas?

QK: Displaying large animations and sprites was the hardest part of development; RPG Maker 2003 is simply not equipped to work with things like it, but I bent it to my will as best I could. I work well under limitations as they keep me focused on the task and force me to be inventive. I would often find myself thinking about something I wanted to do with the engine, then run into roadblocks; in those situations, I would usually either modify those ideas to work, or to circumvent engine limitations.

MP: What are you most proud of with An Outcry?

QK: The Manshrike debate scene comes to mind, as well as the finales of both the game’s “FOLLOW” and “IGNORE” route. They are an enormous effort that the entire team had a hand in, and I think they say their piece beautifully. I also think the city belt scenes came out well and showcase what I think is some of my best writing.

MP: If I understand correctly, this is your first game. How has it felt receiving such a positive response from players about it?

QK: It is actually my third original game! I made a short Twine title, called Ah, in 2018, and the more well-known There Swings a Skull in mid-2021 in collaboration with two other folks. The positive response to An Outcry and There Swings a Skull alike has been motivating me to keep working in games and begin dabbling in 3D development.

MP: What lessons have you taken from your experience creating An Outcry? How do you think your work on this game will change your approach to future titles?

QK: Keep the team small, scope limited and ambitions within reach, but to not stop dreaming, and to keep finding ways to make strange things.

Dread XP and I would like to thank Quinn for their time and remind readers that you can pick up An Outcry on itch.io and Steam. You can also check out our review of the game to learn more.

Categorized: Interviews