Dasha Nekrasova Interview: How ‘The Scary of Sixty-First’ Turns Jeffrey Epstein’s Crimes Into Shocking Supernatural Horror

In Dasha Nekrasova’s debut horror feature, The Scary of Sixty-First, the ghost of Jeffrey Epstein sweeps into the lives of some disaffected twenty-somethings and turns them inside out.

At the center of this film’s psychosexual universe are three women: Noelle (Madeline Quinn), Addie (Betsey Brown), and a mysterious stranger simply named “The Girl” (Nekrasova). Noelle and Addie are roommates, and it’s not long after they move into an unusually affordable apartment on New York’s Upper East Side that they learn it was once owned by Epstein. The Girl—an amateur investigator of elite conspirators—is the one who alerts them to the place’s history, when she knocks at their door to tell them that “something extremely sinister” happened within its four walls.

From there, things only get weirder and wilder. While Noelle and The Girl fall into a rabbit hole of research that puts them in mortal danger, Addie’s body—and even more unsettlingly, her sexual behaviors—are suddenly seized by the spirit of an underage sex trafficking victim.

As co-host of the podcast Red Scare, Nekrasova has frequently obsessed over Epstein’s death and its mystifying details. Her protagonist in The Scary of Sixty-First is an authentic and inspired embodiment of that obsession: deeply paranoid, but not without good reason, and desperately seeking out terrible truths that have yet to be uncovered.

Speaking with Dread Central, Nekrasova is characteristically unshy about calling Epstein’s death a “murder,” and cues us into the headspace she was in as she made her manic first movie.

Dread Central: You said in an interview a couple of years ago that the truth of Jeffrey Epstein’s crimes makes you “extremely hopeless,” and that you feel like “We’re already in hell.” And your character in The Scary of Sixty-First says the same thing, that “We’re already in hell.” Can you unpack what that line means to you and how that worldview sets the tone for this film?

Dasha Nekrasova: In late 2019, after Epstein was murdered, I, much like my character, was in a lot of anguish about the realities of the corruption of the ruling class—specifically, as it pertains to the global sex trade and human trafficking. I was also traveling a lot to Thailand for work. I was shooting a TV show in Bangkok—seeing wealth disparity on a global scale, and having an understanding that that wasn’t an accident. That there were people in power who had amassed unethical amounts of wealth at the expense of everyone else. And that certainly felt—and still feels—hellish to me [laughs].

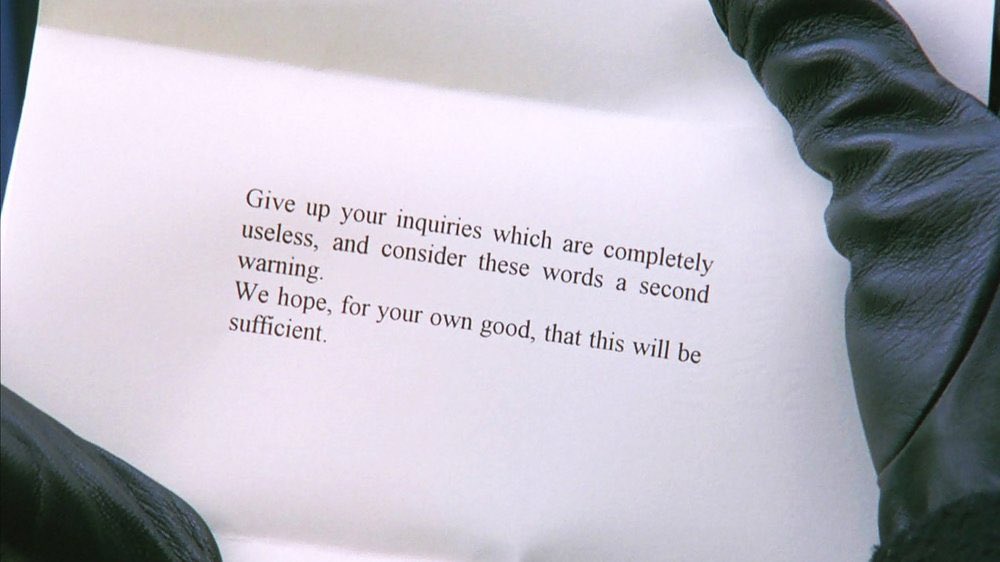

DC: There’s a sense of futility about that—of inescapable doom. And that feeling ties into the end of the film, which includes a lifted line from Eyes Wide Shut…

Nekrasova: Right. “Give up your inquiries, which are completely useless…”

DC: Exactly. Does that play into the idea that it’s useless to resist against these enormous power structures?

Nekrasova: I wouldn’t say it’s useless. But the film does take place in the Eyes Wide Shut extended universe. And I think that Stanley Kubrick did understand things about power and global power systems—which he deals with in all of his films, but very explicitly in Eyes Wide Shut. So yeah, there is a sense of futility. But I wouldn’t say that I’m completely nihilistic about it. I think that there still is virtue and purpose in pursuing justice, certainly.

DC: Yeah, the act of making this film is a testament to that. As far as Kubrick’s film goes, you said that he understands power… How does that translate to your perspective on power in The Scary of Sixty-First? Does it come through more in the style of the film, or in its themes?

Nekrasova: It’s definitely thematic. In terms of style and approach to filmmaking, it’s very different from what Kubrick does. And in that way, it’s less of an homage and more of a love letter. Kubrick avoided power. He moved to the UK. He said at various points in his life that power is dangerous and should be avoided. And while on the surface, Eyes Wide Shut is this marital drama, what it’s really about is elite power structures and Tom Cruise’s character’s place within them. And about their totality and control.

DC: Eyes Wide Shut is often read as this dreamlike allegory. But I’m curious if you do see it more as a literal depiction of the elite underworld. Both interpretations are pretty valid.

Nekrasova: Yeah. Well, Eyes Wide Shut had this little renaissance—a cultural zeitgeist resurgence, after Epstein’s death. Because all of the details of the Epstein stuff really did lay bare that the elites are fundamentally perverted [laughs]. And that they are enacting these quasi-Satanic rituals.

DC: Some of the symbols of those rituals are present in your film as well. Did you do a lot of research on that stuff? Was the history behind those symbols of interest to you, or was it more that you used those symbols to suggest something “sinister”?

Nekrasova: I had done a lot of research on Epstein even prior to starting scripting. I wouldn’t even call it research. I think it was just kind of a compulsive, borderline manic fixation on the details of the Epstein stuff.

DC: [Laughs] Relatable.

Nekrasova: [Laughs] Yeah. I think a lot of people were. I mean, that’s why “Epstein didn’t kill himself” became such a powerful meme. It put it really succinctly: that Epstein didn’t kill himself, and that beyond that, he was murdered to preserve elite interests. The idea being that had he been brought to trial, things would’ve come to light about a lot of people in power.

So yeah, I had done a lot of research prior to writing. The occult stuff was more refined and focused with the interests of the film in mind. I’m not really interested in the dark arts myself [laughs]. But with the details of the Epstein stuff, and all of that information in the film, it was really about selecting what was the most visually compelling and the most legible.

That’s also why his island is so prominently featured, because it’s so scary. And in New York, we had the locations of the prison where he was held and his townhouse available to us, surprisingly. And those places had their own very intense and frightening aura. The photograph of Prince Andrew with Virginia Giuffre, we had all seen it so many times that it felt important to visually represent that.

I was trying to establish a visual vocabulary in the film—and to give as much expository information as I could without having a character, say, Google something [laughs]. Which is why my character carries around that briefcase that’s full of ephemera.

DC: Her laptop screen is also littered with all kinds of folders and photos related to the Epstein case. I know you’ve said that this film was born out of a kind of mania, and your character is also wrapped up in this manic obsession with what she’s investigating…

Nekrasova: Yeah! I mean, I was manic, much like my character. There is this kind of drug culture within the film: There’s allusions to Betsey Brown’s character, Addie, taking Ambien, and my character was on amphetamines. Amphetamines obviously contribute to mania [laughs], and I was definitely on a lot of them when I made the movie. So, that infiltrated the whole project: the way it was made, how quickly it was made, the state that we were all in. The movie also takes place in December of 2019. We shot it in January of 2020, so we were basically making it as close to in real-time as we could. And I think that that comes across [laughs]. The movie is successful to me in that it’s a very accurate artifact of that time and place, in my life at least.

DC: When it comes to the supernatural and possession elements in the film, I understand that they were inspired by real-life cases in Malaysia, where women factory workers were having these convulsive episodes.

Nekrasova: There was a phenomenon in Malaysia with female Malay factory workers, around the time when Malaysia was starting to become industrialized, where they were being seized by spirits on factory floors and disrupting production. I had read a book a long time ago—an ethnography called Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline—and it stuck with me. And I did talk about that book with Betsey.

The phenomenon in Malaysia was inspiring to me in the sense that it was a kind of resistance. So, we used the metaphor of spirit possession as a kind of nonlinear resistance—as a way of becoming unmanageable and disruptive. In the scene where Betsey’s character is at the townhouse and she’s seized by this demonic spirit, we’re also in the place where Epstein actually lived, and we’re desecrating it. So I wanted the scene to have a disruptive or rebellious tone to it.

DC: So, on one hand, her character lives under the power of this sexually predatory spirit—but on the other hand, you’re reclaiming some of that power by defacing Epstein’s real-life home.

Nekrasova: Yeah. I mean, the ethnography about the Malay factory workers doesn’t set out to investigate whether they were really possessed or if it was psychosomatic, or what that phenomenon was. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter. Because functionally, it was real. It was real enough for them. You could make the case that it was the influence of capitalism and industrialization that caused them to have these experiences—and that the real demon that they were possessed by was capitalist discipline and production.

DC: And so the “possession” is an acting out of what people have internalized from their surrounding culture?

Nekrasova: Yeah, yeah. And in the case of Scary, Betsey’s character is the most vulnerable, which is why she becomes a vessel for this evil force, whatever you want to call it. But it’s also about taking the very real way in which girls are sexualized at a very young age in our culture. We do have an ephebophilic, borderline-pedophilic culture. And so in the film, we take those proclivities and make them grotesque and problematic and disruptive.

DC: Have you considered your film’s relationship to others in the conspiracy horror genre? Or would you say this movie exists apart from all that?

Nekrasova: I love They Live, but I can’t say it’s an influence. The Conversation was a reference, and something I spoke about with [co-writer and co-star] Madeline Quinn and my cinematographer, Hunter Zimny, in terms of conveying paranoia. The Parallax View comes to mind as well. But I think I was working more with the tropes of horror and psychological thriller, rather than conspiracy films per se. Because I mean, to me, the Epstein stuff isn’t really a conspiracy.

DC: Yeah, it isn’t just a “theory,” you’re saying?

Nekrasova: Yeah. As my character says in the film, “I’m not a conspiracy theorist. The only conspiracy is between the elites, who depend on a permanent underclass for them to exploit.” That is the thesis of the movie.

DC: Maybe this question is cliché, but did you feel like making this film was dangerous at any point, considering how directly you confront Epstein’s crimes? Did you feel like calling them out put you and your cast and crew at risk?

Nekrasova: No, but I’m very brave [laughs]! There’s also an aspect of disillusionment as well. It’s kind of this capitalist realist idea, where things that are subversive or transgressive get absorbed into the mainstream as a means of disempowering them.

DC: Yeah. I’m curious because I spoke with the director of The Pizzagate Massacre, and he’s gotten a ton of death threats since releasing that movie.

Nekrasova: Really? From who?

DC: From people who don’t like that he’s satirizing Pizzagate, or conspiracy theories about reptilian shape-shifters.

Nekrasova: Oh, right. He’s doing a different project than I am. I have a lot of empathy for people who do believe in the more far-out, reptilian stream of conspiratorial thinking. Because I think reality is so fractured. There is such a mass mistrust of dominant narrative, and it makes sense to me that there is. And however people want to make sense of this increasingly unjust and confusing world is valid, I think. Like, it doesn’t matter if Nancy Pelosi is a lizard, because she acts like one anyway.

DC: Right! When people latch on to these more far-fetched conspiracy theories, it’s rooted in this belief that the government doesn’t have our best interest in mind, even if they’re not lizards. So for them, the lizard thing is just the next logical step.

Nekrasova: Right, right, right. Like, they don’t have to literally be drinking babies’ blood, because the atrocities that they’ve committed are tantamount to that level of evil anyway [laughs].

DC: So, The Scary of Sixty-First is only your first film. Do you feel like you’re growing comfortable with being an “emerging genre filmmaker”? Are you interested in sticking around to tell more horror stories?

Nekrasova: Yeah, my next film is also genre. It’s called Total War. It’s a horror film that takes place in the aftermath of the American Civil War. And it’s a period piece, so it’s a little larger in scale… still pretty contained, though, it’s not like a war epic or anything. And, a lot like Scary, it still deals with unsustainable power dynamics between characters, as well as supernatural and psychedelic elements.

I started working on it four years ago with another writing partner of mine, Robert Barnett. We shelved it, and when Scary started to get traction, I found myself really thinking about it again and becoming obsessed with it aesthetically and thematically. So, we polished it up and made some revisions to it, and we now have a serviceable draft.

So, that feels like a good next film for me to make. I hope I get to. I think it’s going to take me a while. I’d like to make something a little more carefully and meticulously than how I made Scary… just because I would love to not induce a manic episode within myself to be a filmmaker [laughs]! And I learned a lot from Scary, so I don’t think I have to. I think I can make something a little more peacefully and diligently.

The Scary of Sixty-First is now playing in New York and Los Angeles, and opens in more cities and on Digital December 24, 2021, courtesy of Utopia.

Categorized:Interviews News