Fantastic Fest Review: ‘The Black Phone’ Doesn’t Quite Connect

The team that brought us Sinister is back with Blumhouse and Joe Hill in tow, to bring what has suddenly become one of the most anticipated horror movies of the year. At its world premiere at Fantastic Fest, director Scott Derrickson and writer C. Robert Cargill were in attendance along with Derrickson’s two sons, Atticus and Dashiell. Before The Black Phone got rolling, Derrickson’s short film “Shadowprowler”—which he shot during lockdown—was screened for audiences. Beaming with pride, Derrickson spoke highly of his kids and helped set the tone early: Tonight is all about family.

The Black Phone is based on Joe Hill’s razor-thin short story of the same name. Hill, the son of Stephen King, tends to write about family quite a bit and this tale is no exception. Hill’s graphic novel Locke & Key explores a magical world that unlocks secrets within an ancestral home; NOS4A2 builds a vampiric dream world for kids from mostly broken homes. And in The Black Phone, a closely bonded brother and sister use the abuse they endure in their lives and the gifts they inherit to help spring a trap that, up until now, no one has been able to escape.

In the Colorado suburbs of 1978, life is tough for Finney Shaw (Mason Thames) and his firecracker of a sister, Gwen (Madeleine McGraw). School bullies await both of them after school and their misguided, belt-wielding, alcoholic father (Jeremy Davies) waits for them after dark. Tough-minded and “touched” with passed-down powers from her mother, Gwen gets the brunt of the abuse, left to scream and cry while Finney watches on. To make matters worse, there’s a mysterious man in a van (Ethan Hawke, as “The Grabber”) who’s kidnapping kids in the neighborhood, and one of Finney’s friends just got nabbed. The Grabber’s victims are never seen again, but once Finney finds himself locked away in the killer’s lair with a disconnected phone on the wall, he discovers that they can still be heard. The phone somehow continues to ring, connecting victims to the one remaining soul that might be able to survive with their help.

The first act of The Black Phone, which establishes the day-to-day drudgery of the Shaws’ family life, falls a little flat, veering dangerously close to the melodrama you might find in a darker Lifetime movie. It’s not the brutality of the child abuse that’s particularly hard to watch—it’s that its execution feels slightly off-kilter, with scenes drawn out in a way that forces the actors, who are trying their hardest, to go for too much. The beats and the beatings early on are important, though, because they provide a blueprint for Finney’s survival once he encounters a much more sinister version of his father in Hawke’s masked killer.

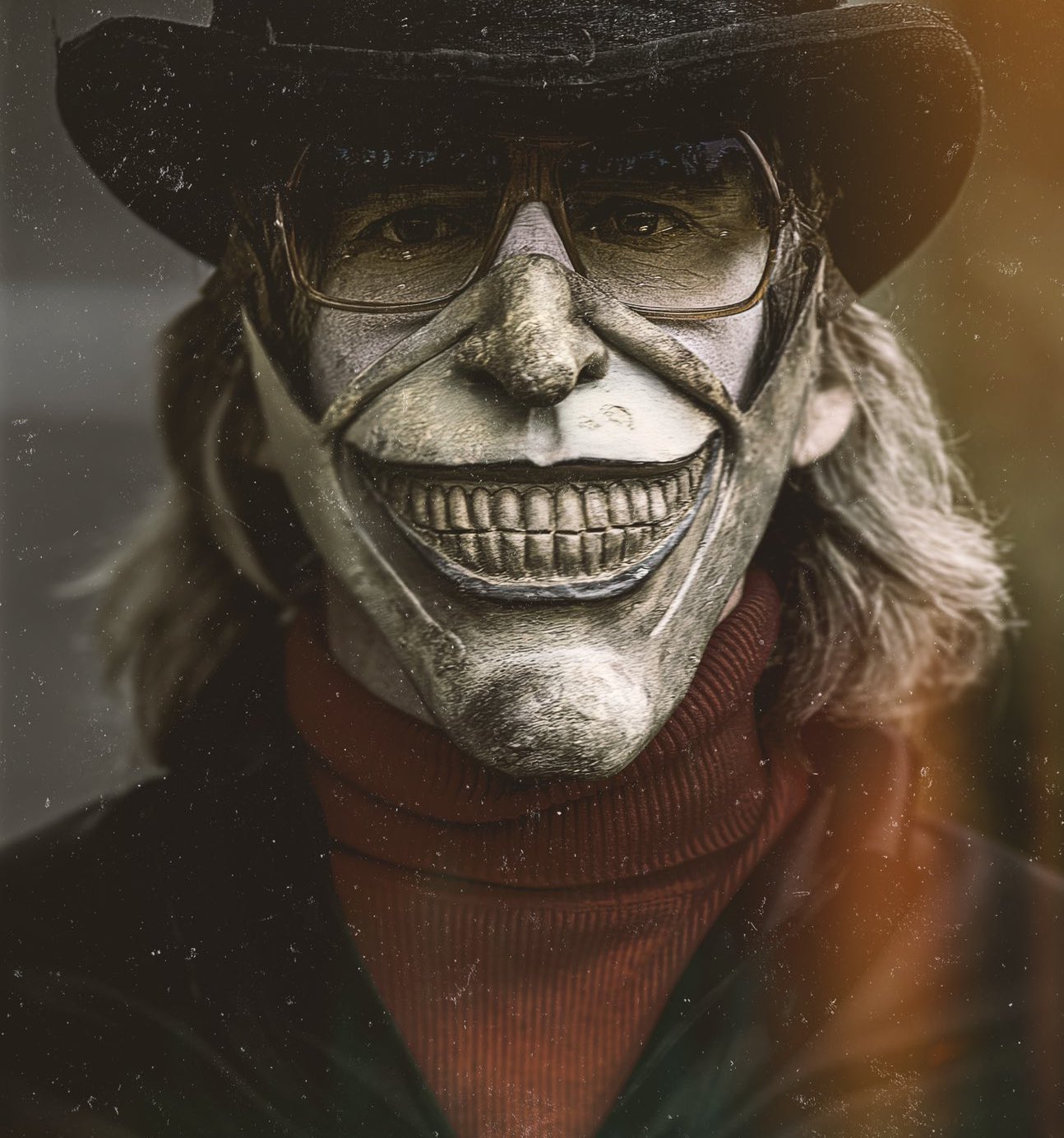

It was undeniably easier to get away with being a serial killer in the late ’70s, but you’d think that it would still be incredibly suspicious to cruise around in a black van filled to the roof with jet-black balloons. Looking like he’s on his way to a goth kid’s birthday party, Hawke’s bumbling magician act seems to work just well enough for him to drug and drag kids into the back and speed away. Unseen for almost the entire film, Hawke’s performance is gleefully macabre and demented as The Grabber plays the game he created—a game that no kid has yet been able to win. Whether it’s a stylistic choice or Hawke’s reluctance to be seen as a child abductor, The Grabber’s face is almost always obscured or hidden away behind a devil-horned Kabuki mask. (Hawke keeps his distance from other actors, as well, so the mask sometimes seems like a COVID precaution.)

Also Read: The Black Phone Poster Is Scary AF

In Hill’s original 2004 short, The Grabber was a clown. But after the success of IT, Hill suggested that the look should be updated. Derrickson came up with the idea to create a three-piece mask through which Hawke’s features—especially his expressive eyes—could still be seen in various change-ups and combinations. Bringing in Tom Savini (yes, our Tom Savini) to help with the design, the decision is especially effective because you’re never sure exactly what Hawke will look like each time he appears. This kind of design touch is something Derrickson excels at, adding instant iconography to a killer that could have come across as a John Wayne Gacy clone.

Landing somewhere in between a sadomasochist and a court jester, Hawke’s performance is fearless. But it’s Mason Thames’ nuanced turn as Finney that keeps The Black Phone grounded when the more supernatural elements come calling. Thames’ tenacity is infectious and makes Finney easy to root for, even when it seems a little too simple at times for him to just run away. The lightbulb ingenuity switching on across Thames’ face gives us flashes of hope, especially when all those dead kids are there to remind us that he’s running out of time.

There’s never a real sense of terror, however—especially since The Grabber doesn’t actually seem all that unstoppable. The character is never quite as scary as those creepy kids who dial a dead line. When his past victims do come calling, they echo haunting warnings of the tortured end they endured, and that should make Hawke’s character more menacing… but it doesn’t. Relying too heavily on quick jolts and jump scares, some moments of The Black Phone feel like the more PG-13 moments of The Sixth Sense. Leaving a potentially terrible fate to the imagination can work on the page, but not always on the screen.

Setting The Black Phone in ’70s Colorado—where Derrickson grew up—seems to be a way of suggesting that kids today would not survive an encounter with this kind of evil. Then again, the kids who died at the hands of The Grabber didn’t quite have the mettle that Finney and Gwen did. Maybe the suburbs are the film’s true villain: There’s something chilling about the thought of heinous crimes being committed right under your nose, not knowing if your neighbor or someone close to you is actually a maniac, hiding in plain sight in the heart of suburbia.

Seeing The Black Phone in a theater with some of the best film fans in America was a special experience—one that stirred these ideas in me as its events unfolded. But honestly, while I’d be eager to re-read this adaptation of Hill’s short story if it existed as a novel, I’m less likely to revisit what we got in this film.

The Black Phone had its world premiere on Saturday at Fantastic Fest 2021. Visit the festival’s website for more info.

-

The Black Phone

Summary

The Black Phone is probably the best Joe Hill film adaptation to date but, admittedly, there isn’t much competition yet. There are still plenty of unique flourishes and powerful performances to entertain the horror masses, though, when this hits theaters.

Categorized:Reviews